Last year Andrew, a computer programmer from Ontario, found himself burdened with a newly redundant asset: air miles. With non-essential travel off the cards, his stash of miles began to appear less lustrous by the day. So, in a vaguely pathos-infused exchange, emblematic of the impact of Covid-19 on our cultural consumption habits, he cashed in his air miles for book tokens.

A regular gallery-goer, Andrew quickly decided on the obvious substitute for the cancelled trips: “I started with the idea that, well, if I’m not going to go to any galleries, I might as well get some books of an entire gallery’s catalogue.” His first purchase was a catalogue from the National Gallery in London. “Then I got one that was, like, all the paintings in the Louvre.” From then, he was hooked. Since March, he reckons he’s bought 30 or 40 art books and catalogues. “Mainly in the evening, I’ll go through and just read them for a while, maybe get through ten or twenty paintings.”

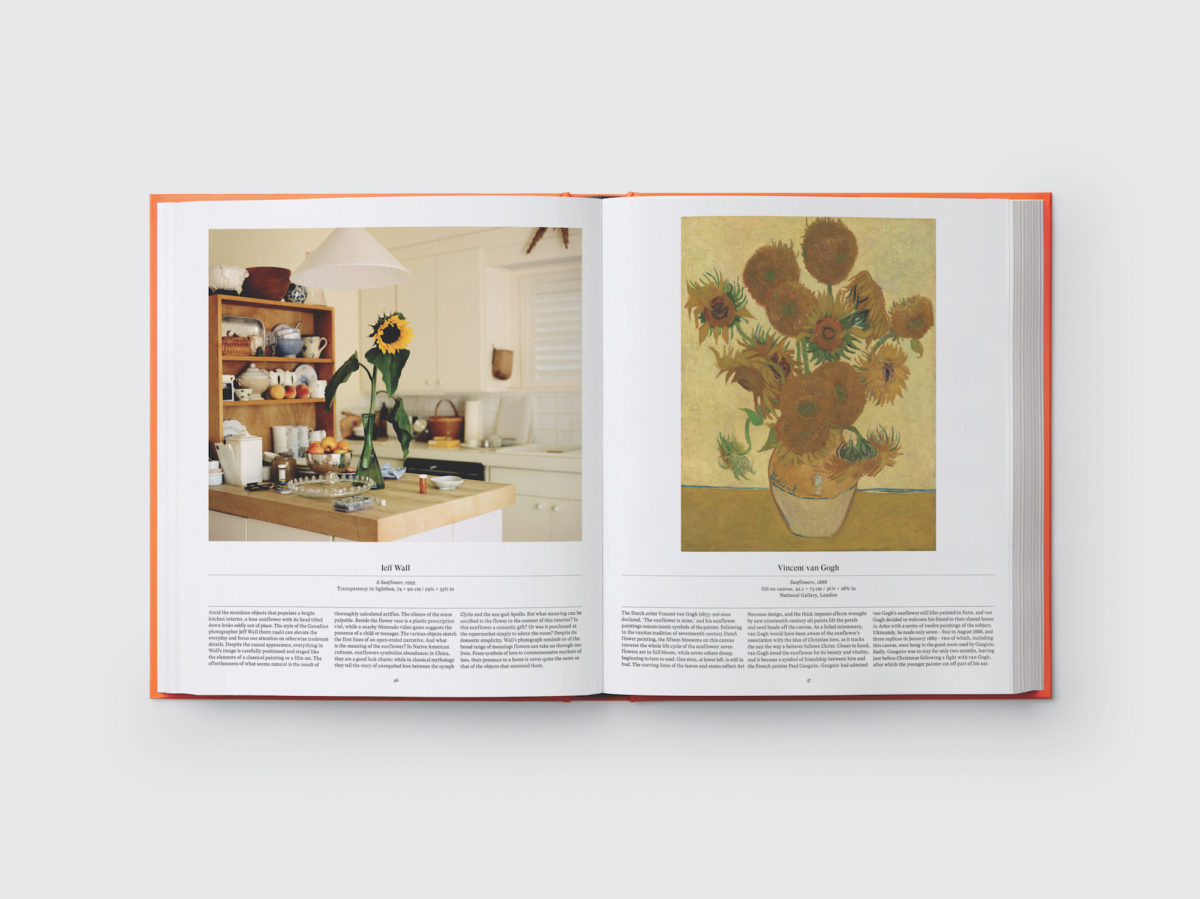

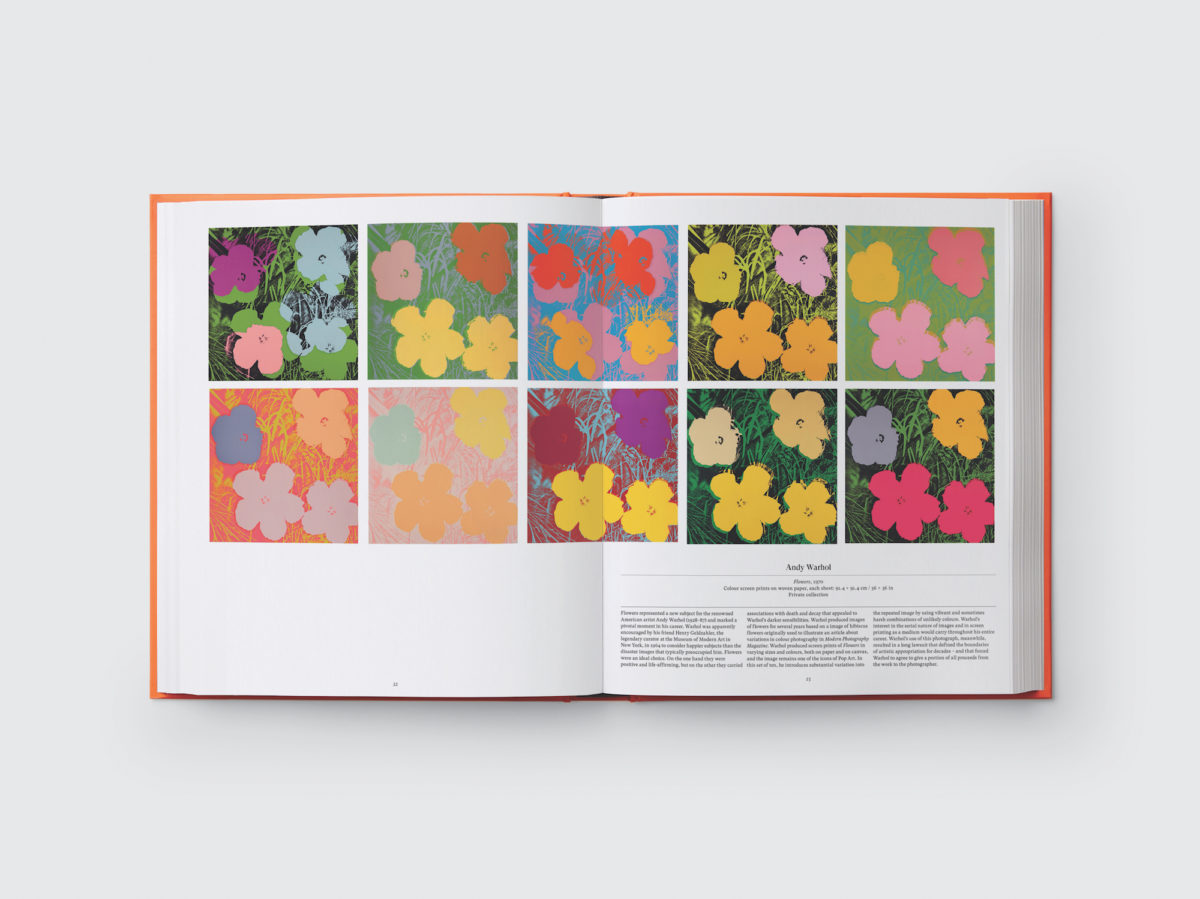

- Flower: Exploring the World in Bloom by Phaidon editors is published by Phaidon

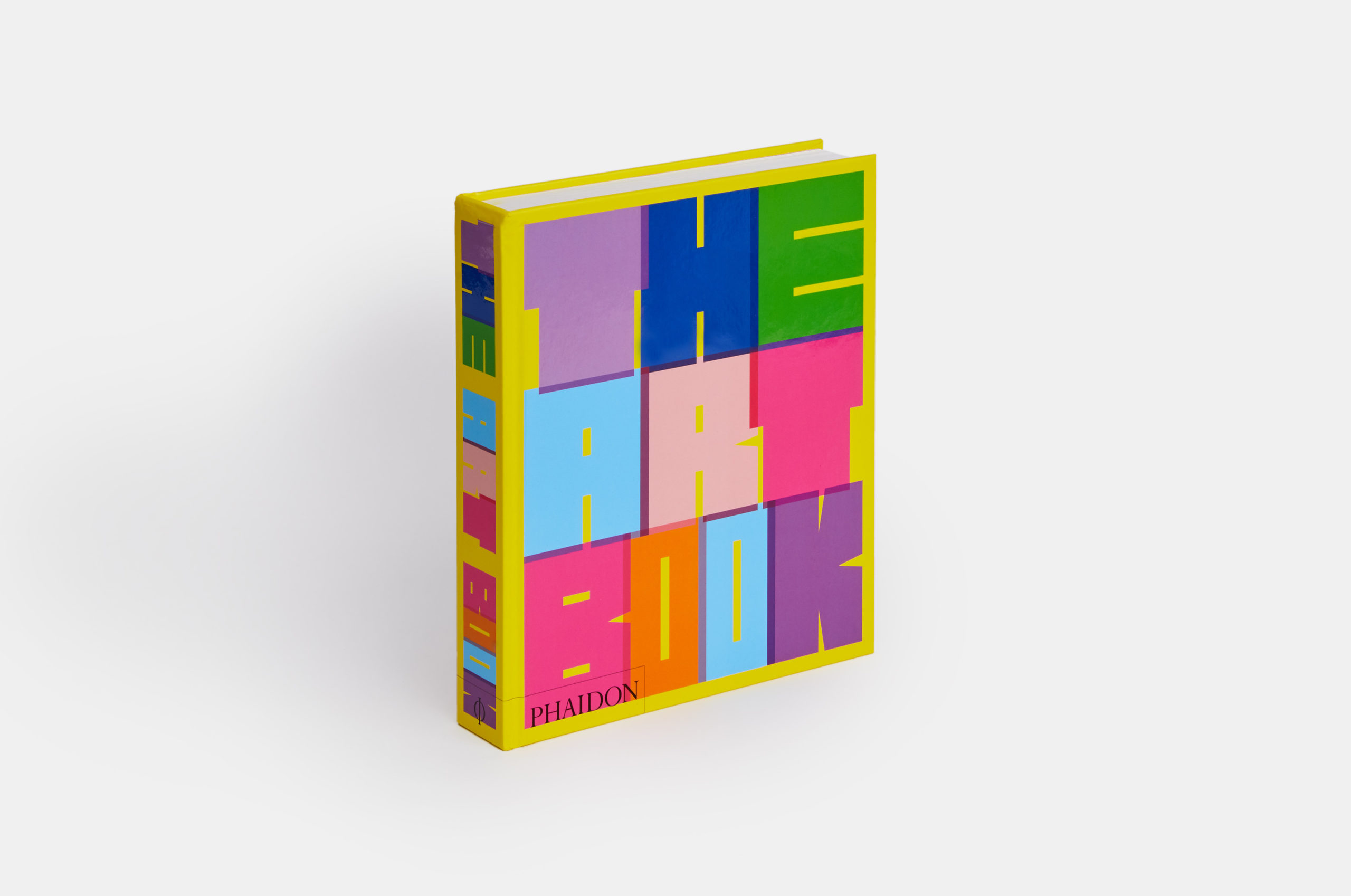

Andrew might have amassed an unusually large collection in a short space of time, but there’s lots of evidence that he’s not alone. In a survey

, two in five British adults said they were consuming more books during lockdown, with readers almost doubling their total reading hours per week. Exhibition catalogues have particularly benefited, as art-lovers turn to print publications to get their fix while galleries are shuttered. “I would say it’s really changing the game,” a marketing representative at art publisher Phaidon said, “in terms of the way publishers sell.” As demand from gallery bookshops and institutional buyers cratered, Phaidon boosted their social media marketing spend, adding momentum to a surge in direct-to-consumer sales.

A press officer at a major national gallery in London told me that exhibition catalogues normally end up gathering dust in back offices, but during the pandemic “there was an overwhelming appetite for physical copies. It got to the point where we had to ration them, such was the demand.” When I tweeted a call-out looking for people to interview about their pandemic-related catalogue purchases, I received more responses than I could possibly include here. Among them, a common rationale emerged. Starved of art but sick of screens, many have sought out exhibition books as a more tangible, first-person art experience that doesn’t involve leaving the house.

“Can books be meaningful surrogates for art experienced in the flesh?”

Some galleries seem implicitly to have endorsed this approach. On the Royal Academy website, a forlorn holding page for the Angelica Kauffmann show offers an alternative: “Although the exhibition has been cancelled, you can still explore the remarkable life and work of Angelica Kauffmann. This beautiful catalogue presents 100 of her best paintings and drawings.” Of course no book, no matter how richly produced, can replicate a gallery full of oil paintings.

Still, the suddenly heightened significance of art books and catalogues has thrown into relief some thorny questions. What is the relationship between exhibitions and the assortment of textual paraphernalia that accompanies, frames and inevitably out-lives them? When should we think of writing and publishing as artistic practices in their own right, rather than merely supplementary? Can books be meaningful surrogates for art experienced in the flesh? If not, do they at least stand a better chance than 3D renders or video tours?

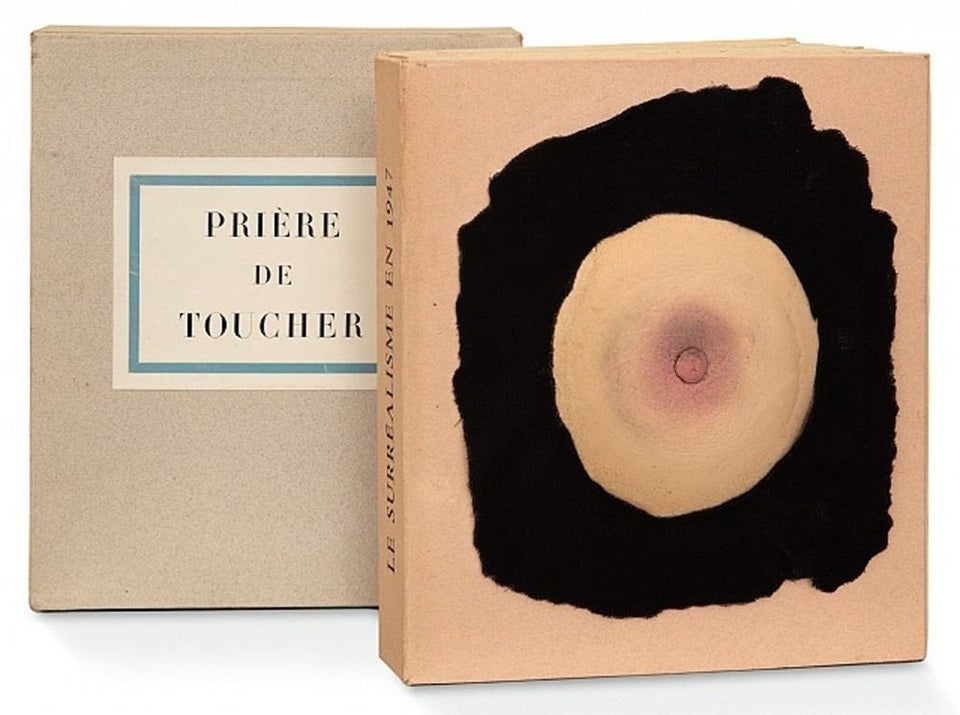

The very earliest catalogues emerged at the beginning of the seventeenth century, as the European art market exploded in size and complexity. They served a practical function, providing prospective buyers and sellers with lists of artists, titles, and dates. As time went on, catalogues became a little more sophisticated—but not much. By the middle of the twentieth century, most catalogues remained staid and scholarly. There were a few experimental outliers; for the 1947 exhibition of Surrealists in Paris, Duchamp notoriously designed a catalogue housed in a box adorned with a foam rubber breast, alongside a label reading “Prière de toucher,” or “please touch” (according to one bookseller, “copies with the breast in fine condition are now extremely rare and desirable”).

“For the 1947 exhibition of Surrealists in Paris, Duchamp notoriously designed a catalogue housed in a box adorned with a foam rubber breast”

But such features were the exception. In most catalogues, even colour photos were relatively rare. “If you were lucky, you might get coloured, tipped-in plates, separated because they couldn’t be printed on the same page as the text” according to Gerrie van Noord, an editor and curator who is researching art publishing. Notwithstanding the inclusion of long (and dry) scholarly essays by art historians and curators, these catalogues were meant to record the exhibition, not replace it. The same goes for most big-ticket exhibition catalogues today, which tend to be hefty, formal slabs of coffee-table book, thick with scholarly text. Ironically, these books can feel weighed down by the responsibility of serving as a sole definitive record, killing the spark that animated the exhibition in the first place.

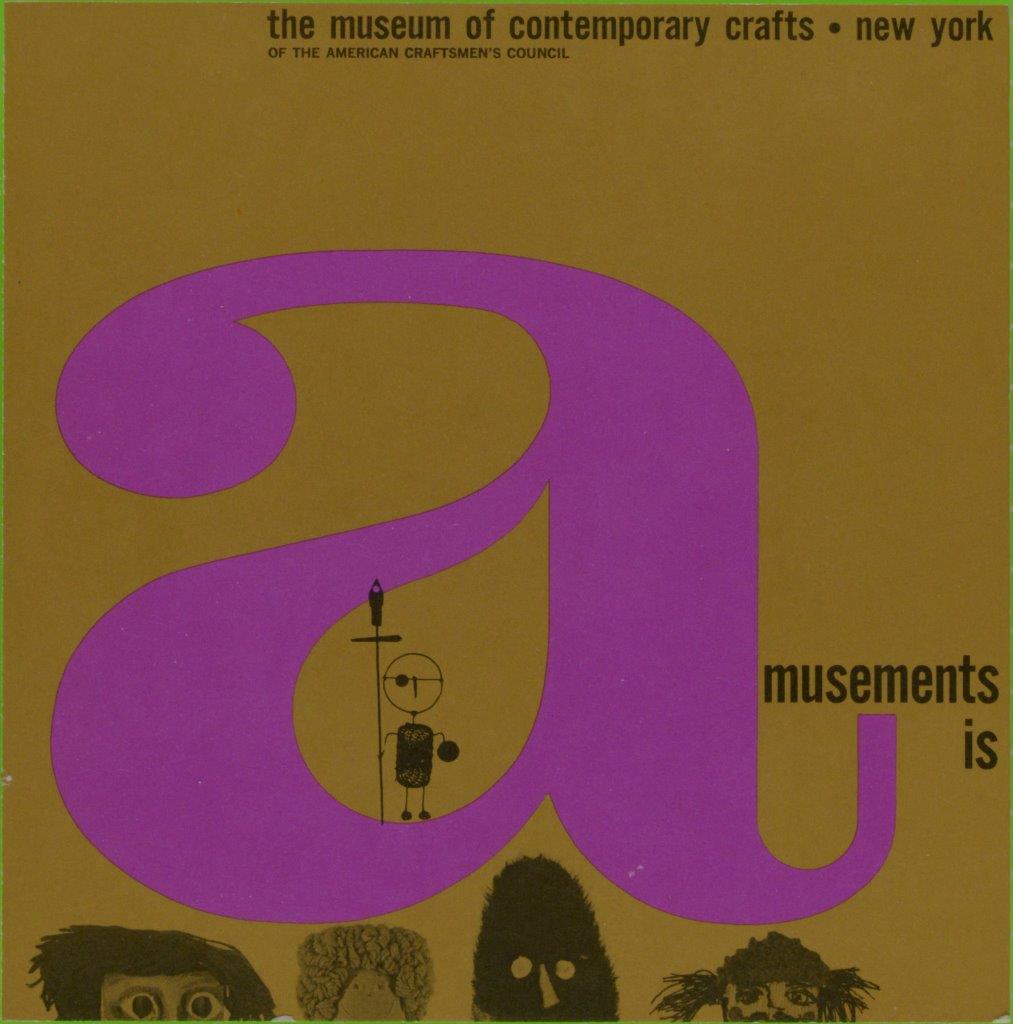

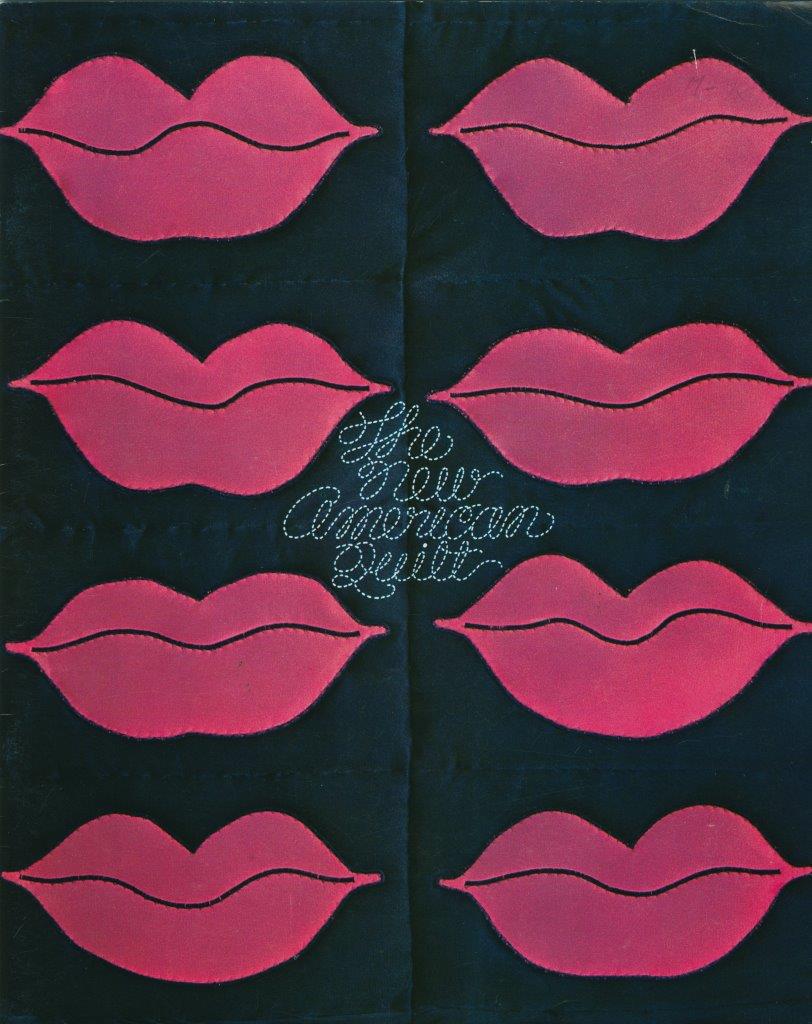

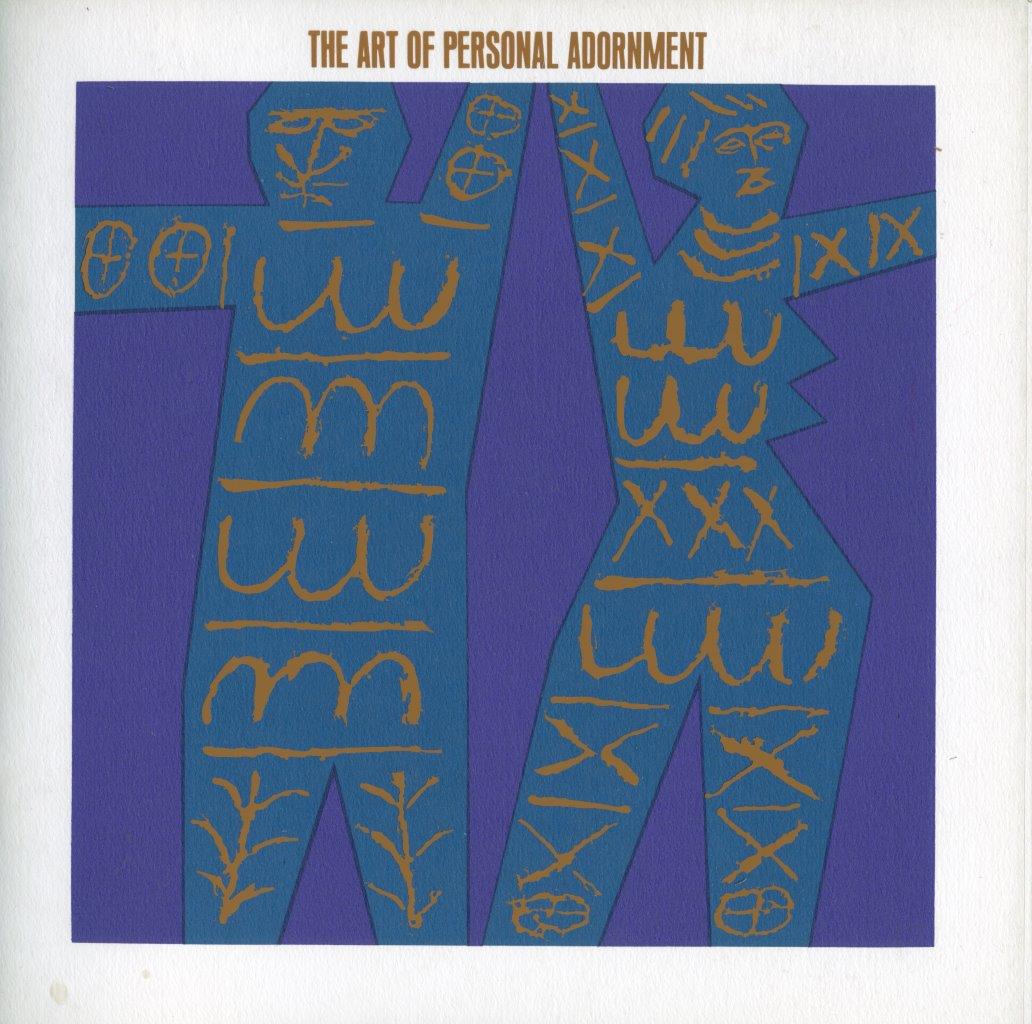

But catalogues can be more than just solemn headstones. Elissa Auther, chief curator at the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in New York, put on an exhibition of 1960s and 70s catalogues and ephemera in 2016. When we speak over Zoom, Auther is armed with a disorderly stack of catalogues that featured in the show, mostly paperbacks the size of record sleeves. As each cover is held up to the camera, a fresh riot of colour and pattern appears: one has a cut-out figure surrounded by hallucinogenic waves of neon green; another the words “Feel It” emblazoned on a ultramarine blue background.

Auther flicks through the pile, occasionally exclaiming and holding up a new copy: “Oh, here’s another great one! Objects for Preparing Food” (a David Shrigley-esque scribble of cups, spoons and whisks). “This one’s good, too; Homage to the Bag” (an image of an ornate stringed purse, plus a folded brown paper bag stuck on with tape). “It has a little bag! Little bags like this were sent out as the invitation, and you pulled out a little card.” It’s hard not to share Auther’s glee. These catalogues are less useful as documentary records—“You’re lucky to even get a full checklist [of exhibits] in the back,” Auther says—but they do give us “a mood, a feeling for the show, the tone of the show… you lose yourself in this feeling that’s being created.” Rather than serving as scrupulous archives, these faintly chaotic volumes intervene in the histories they record.

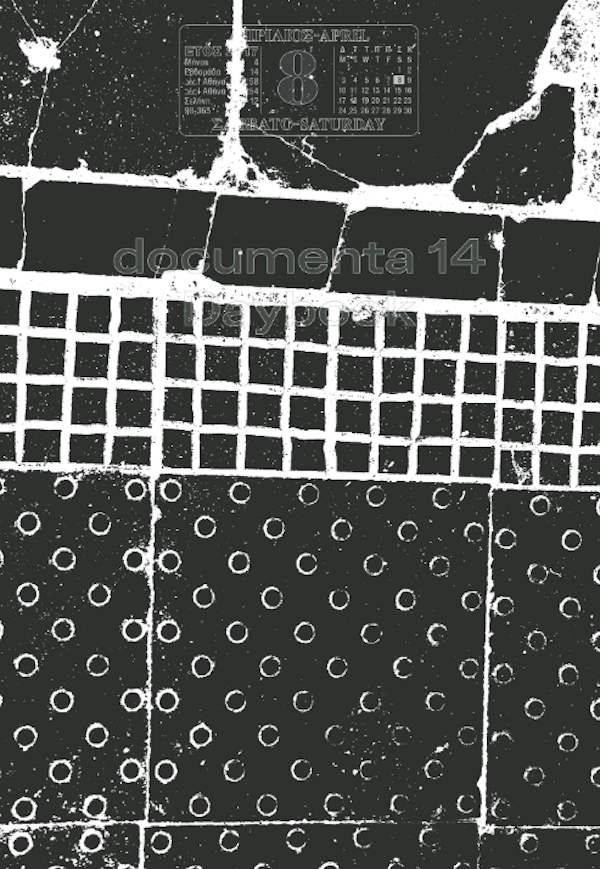

The MAD catalogues have a distinctly 1960s flavour, influenced by the irreverent self-reference of conceptual movements such as Fluxus. But even today, many people’s pandemic-related book purchasing appears to have been motivated by a similar desire for playful, tactile, whimsical objects—even if they don’t provide a completely transparent account of the exhibition they’re attached to. In fact, some catalogues seem actively to militate against giving a decipherable account of the show. Ed Liddle, an artist and curator, showed me an especially anarchic volume: the “daybook” from the 2017 edition of documenta, the prestigious German exhibition staged once every five years. The book includes a clamour of curatorial text, poetry, short stories, letters and just about every form of writing imaginable—save for a contents page, an unfortunate omission given that artists are afforded calendar “days” in the book in non-alphabetical order, making it virtually impossible to look them up.

“If the object of pandemic book-buying is to get away from the screen, it makes sense to look for works that draw attention to their own contingent physicality”

Josh Hall, a culture writer, told me that alongside more traditional catalogues—Miró, Kandinsky—he’d turned to the messy materiality of photography zines: “I like the physicality of it; to be able to see the construction process, where the joins are.” If the object of pandemic book-buying is to get away from the screen and have a richer, more sensory engagement with art, it makes sense to look for works that draw attention to their own contingent physicality, their here-and-nowness, rather than struggling to provide a transparent window to a real-life experience that happened in another place, at another time.

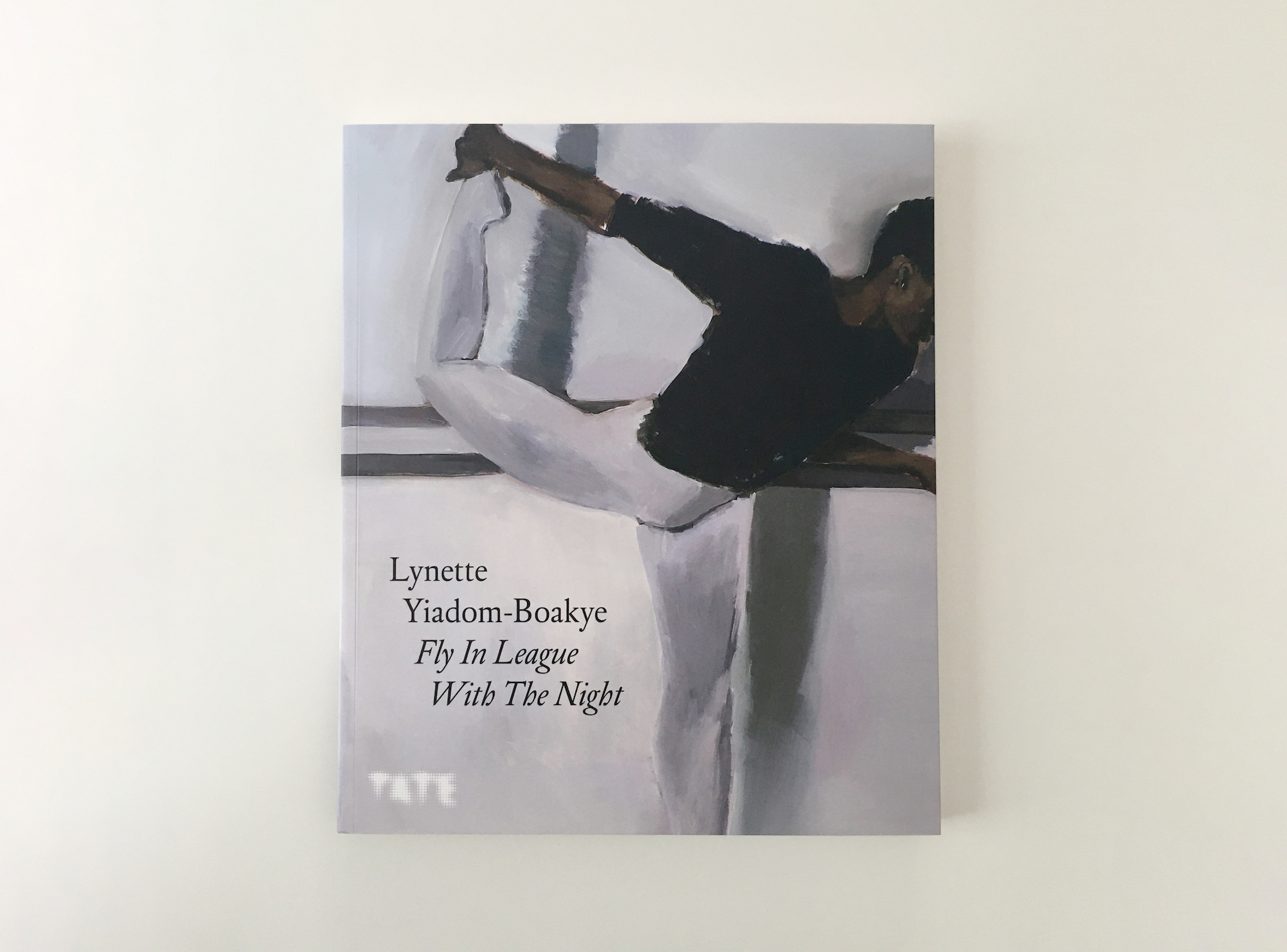

Still, is it ever possible to say that books—even the most physically striking ones—offer a worthwhile substitute for walking through a gallery? Isabella Maidment, curator of contemporary art at Tate Britain, had time to ponder that question this year while the exhibition of paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye that she curated is temporarily closed. A catalogue “can never be a substitute for the work itself,” Maidment says, “particularly with painting, which can never be reproduced faithfully—it just can’t.” But this exhibition’s book played an especially important role. As well as a painter, Yiadom-Boakye is a writer of poetry and prose, and the publication included new writing by her. Consequently, Maidment says, “we always thought of it as an extension of the exhibition.”

In this sense, Yiadom-Boakye is emblematic of a broader artistic trend. As research and theory underpin the most conceptually innovative art to an increasingly fundamental extent, the line between artists and writers has blurred. “There isn’t just the object and then people who write about the object,” Gerrie van Noord says. “No—there are different platforms where creative thinking can manifest itself.” For those of us who are buying art books and catalogues as a lockdown salve, this is a heartening perspective. But I’m not getting rid of the air miles for my next art trip just yet.