With a singular undertaking, each artist tells a personal story to build a mosaic of the American reality.

The new Whitney Biennial is a wet show. It is also earthy, rugged, or, at times, metal-cold. There are cracks, oozes, and gleams. The title Even Better Than The Real Thing hints at this tactility: reassuring the uncompromisable joy of the authentic—whether in touch or feeling. The heading urges us to internalise the art on view by seventy-one artists with the promise of something better than the real thing; we are prompted to soak in what we see, penetrate into it, wear it, and get lost in it. Parallel to the textures prevailing, the work spread on the museum’s top three floors, and the entrance gallery, the curators Chrissie Iles and Meg Onli let the air claim its own territory—there is potency in the invisible.

The installation is spacious and breezy. The organisers relish on a show that is loose in its theme and determined in its fluidity. With enough room to manoeuvre, Onli and Iles carve islands of statements in each work, letting individual consistencies and textures exist—all the pores open, and what the main wall text describes as a “dissonant chorus” gushes its variant tunes. Synchrony is not the core impetus in this orchestra, and neither is a crescendo: the thin line between noise and melody rather chimes throughout. While a sensory crescendo is bypassed, the show’s physical peak is Torkwase Dyson’s gargantuan abstract tour de force, a wood, steel, absolute black granite, basalt, graphite, and acrylic sculpture titled Liquid Shadows, Solid Dreams (A Monastic Playground) ( 2024) on the museum’s fifth-floor roof. Towering, gothic, and beautiful, the pitch black angular two-piece workhouses its bystander with its rounded roofs on each side and stands against them with its soaring wall. Dyson’s practice is atomic and explosive with its eschewing of scale hierarchies—she transforms the most intricate drawing into a massive body of sculpture or attributes architectural musings intimate linearities. Touching the sculpture at night under the lunar breeze, the wood feels as cold as steel.

Warmth lives inside through the spring colours of Suzanne Jackson’s acrylic, gel, and detritus paintings that inhabit a sixth-floor gallery of their own. Some suspended from the ceiling—in one work with a vintage dress hanger and an S hook in the other—or a few covering the walls, they each are individually-formed organisms with tulle-like transparencies as well as firmness through Jackson’s dense colourings with blue, red, ruby, and yellow. They are sandy in some instances, perhaps coarse, and in other cases, paint and gel pool into a soft touch. Fissure is inherent to Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio’s sun-facing sculpture Paloma Blanca Deja Volar / White Dove Let Us Fly (2024).

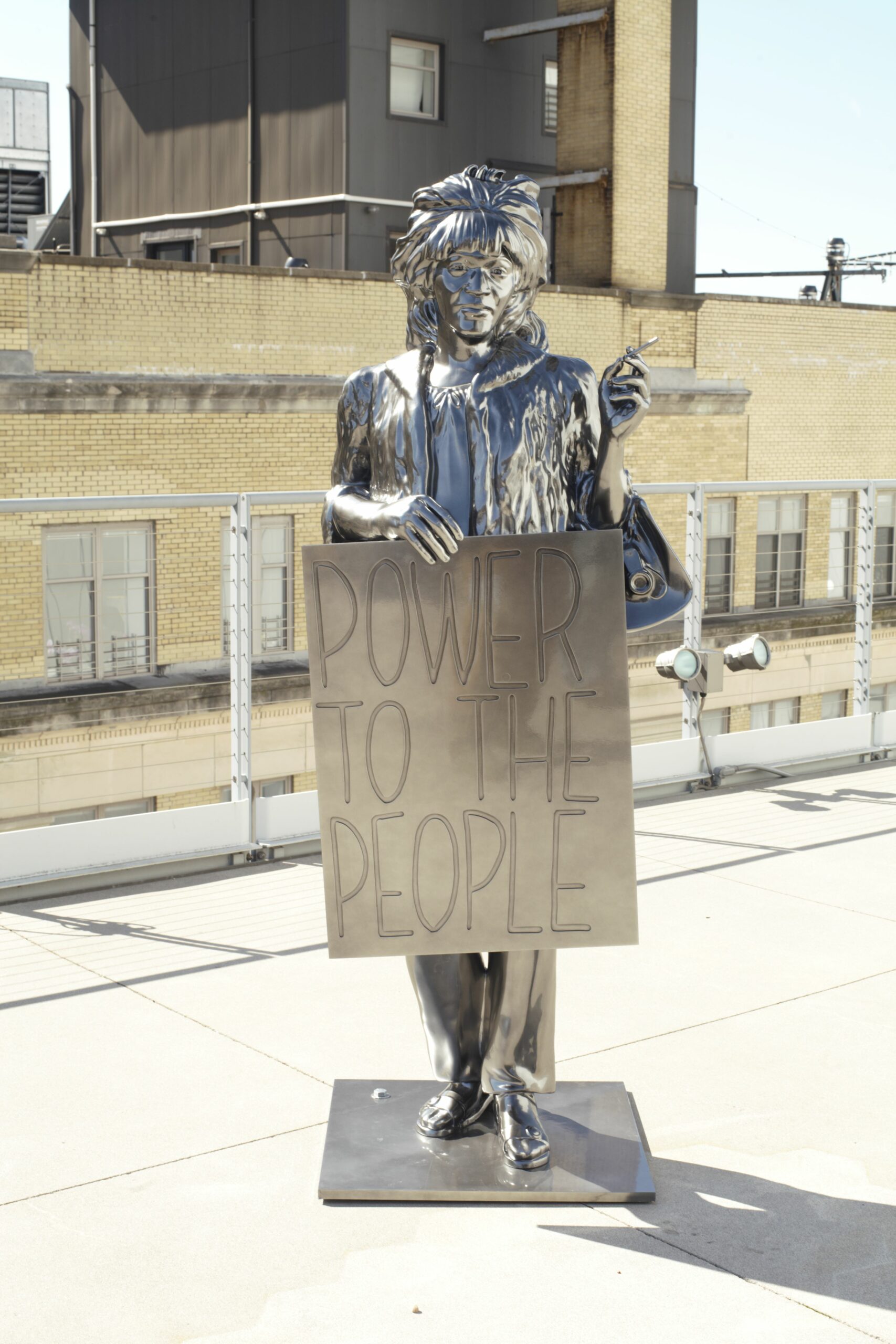

Perched by the ample sixth-floor window, the large rectangular form is of modified amber, volcanic stone, pigeon wings, ceramic, cloths, archival documents and found objects, and by the morning of the work’s debut on Tuesday, the first crack had already happened. The artist intends the work to transform and open up over time to reveal the found bits embedded inside the honey-coloured amber. Aparicio assumes the work’s main material as a reference to the trajectory of migration in the US, especially to the arrival of Central American and Mexican workers in the mid-20th century, which was followed by their deportation, concurrent to the removal of amber trees in California due to their wide roots. The sun, which will dent more openings on the glassy amber surface as the spring leads the way to the summer, will also heat up Kiyan Williams’s aluminium terrace sculpture of Marsha P. Johnson.

Lifesize with a sign reading “POWER TO THE PEOPLE,” Statue of Freedom (Marsha P. Johnson) (2024) embodies the Stonewall leader on the west side waterfront where once she stomped and fought. With pier’s gusts reaching her aluminium body where the sun paints its sheen, the sculpture becomes a furnace of passion, a whirlwind of history and the very moment embodied in Johnson’s elegantly forceful poise—she stands far from everything inside, in her own positioning, and once we are outside by her, Johnson is there, with the backdrop of the piers. The softness of the bedroom is imbued in Harmony Hammond’s quilt paintings which possess cement-like surfaces and vehement linings with drawing-like seams. They are corporal, unexpected, stitched, and desirous.

One painting holds a carving painted in a sanguine red, which evokes an abrupt incision. The feeling of being wrapped and protected in a bed is in Hammond’s quilts as well as the insecurity of existing as a politicised body. Against Hammond’s creamy tactility, Ektor Garcia’s sequenced cosmos is woven in copper wire. Intricate patterns in desert red are soaring in scale and delicate in mass, with blossoming patterns in sweeping configurations. Garcia’s gentle weavings, which also include shells, horsehair, and glass bits, are both weightless and austere, light and compact. They have melodic motifs and a hospitable presence in a show of ambitious material palettes.

In Jes Fan’s sculptures of his 3D-printed body scans, corporal familiarity is distilled through the malleability of the cerebral. Polylactic acid filaments, resin metal, and pigment blend with glass, a material Fan has long been involved with, for oozing forms that are stern and glossy in texture. The artist uses the architecture of the gallery space akin to a body: in Gut (2023), he conceals a replica of the contouring of his stomach inside the drywall, only visible through three orifices-like cuts through which interiority is performed. Motion ascends to catharsis in Isaac Julien’s dark room installation Once Again… (Statues Never Die) (2022), which invites the viewer to cruise around a 31-minute black and video. Separated into five screens, the moving image narrates the story of Harlem Renaissance key figure Alain Locke in Julien’s signature highly aestheticised, sensually stimulating style. The philosopher’s ideas on art from Africa and its diasporas are uttered by actor André Holland, while plaster or wooden bodily sculptures by another Harlem Renaissance symbol, Richmond Barthé and the Whitney Biennial alumnus Matthew Angelo Harrison extend the film’s prompts about restitution and autonomy to three dimensions.

A sense of being worn lingers in Ser Serpas’s ground floor installation, the urban grit’s brushstroke paints the discarded objects she collected from Brooklyn streets. Serpas concocts her findings like poetry verses with the alchemy of an intuitive logic. An unlit disco ball crowns a toppled crusty laundry cart that sits atop tired gym equipment that stands tall. A rusty fire hydrant plays dead above a metal-shelled cart. Tattered on their surface, the objects challenge us to see their beauty, but like in any piece of poetry, freeing the senses goes a long way.

Written by Osman Can Yerebekan

Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing is on view from 20 March until 11 August.

find out more