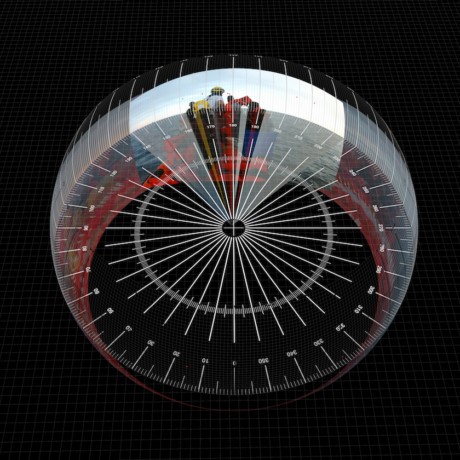

Image: Forensic Architecture and Dr Salvador Navarro-Martinez, 2017

A growing number of people are slowly gathering in the lower gallery of the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London to hear Eyal Weizman talk about truth. “We will demonstrate this clearly,” he says, enunciating every syllable, with very real pride in his voice at the prospect.

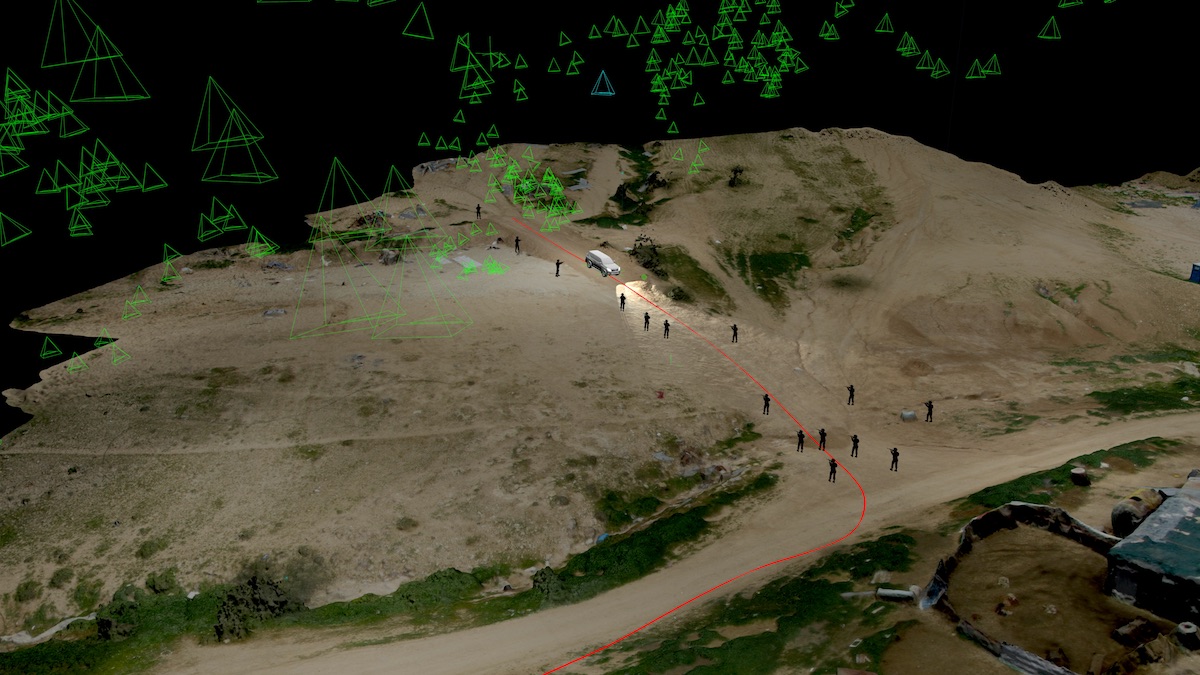

Weizman is talking about the case of Halit Yozgat, investigated last year by Forensic Architecture, an agency that uses architectural techniques of modelling and spatial analysis to contest the official narratives of crimes in which nation-states might have been involved. They do this by using forensic methods which have typically been the preserve of governments, and by demonstrating their results in a range of public spaces: art galleries, courts, tribunals. The exhibition at the ICA will run concurrently with a series of seminars, lectures and workshops. For Weizman this way of working is a return to the original etymological root of “forensis”––of or pertaining to the forum, to the public place of discussion.

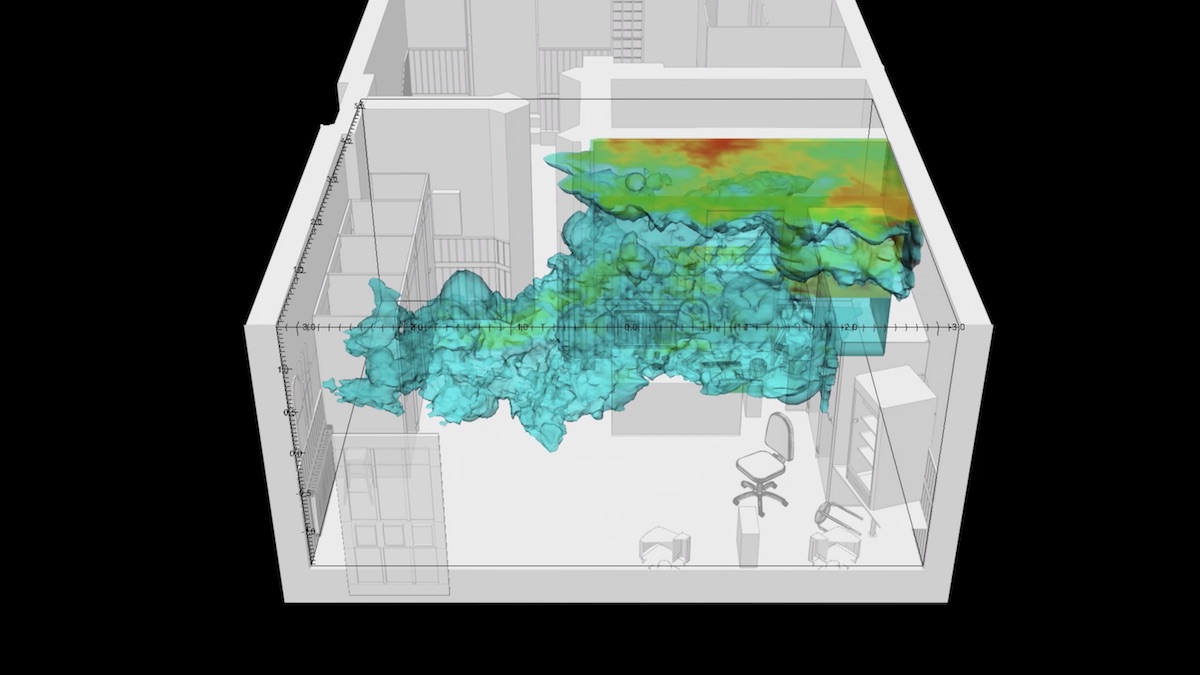

Image: Forensic Architecture, 2017

Halit Yozgat was murdered while working behind the counter of his internet cafe in 2006, in the German town of Kassel. The killing was part of a string of racist assassinations carried out by a right-wing organisation called the NSU (the National Socialist Underground), crimes which were suppressed and mischaracterized for many years by German police and wider society at large as violence within and between German Turkish communities.

Yozgat’s murder took an even stranger turn when it transpired that a German intelligence agent, Andreas Temme, was present at the scene of the shooting, sitting at a computer in the internet cafe. He claimed not to have noticed the crime. When challenged, Temme stated that he had, minutes after two shots were fired in the shop, walked out: placing his money on the counter, not noticing the dead body which lay behind it. On the floor of the ICA a life-size recreation of the floor plan of the tiny shop, marked out in white tape, plainly shows how ridiculous it was for Temme to claim that, while he browsed on his computer, he did not notice a man being shot and killed a few metres away.

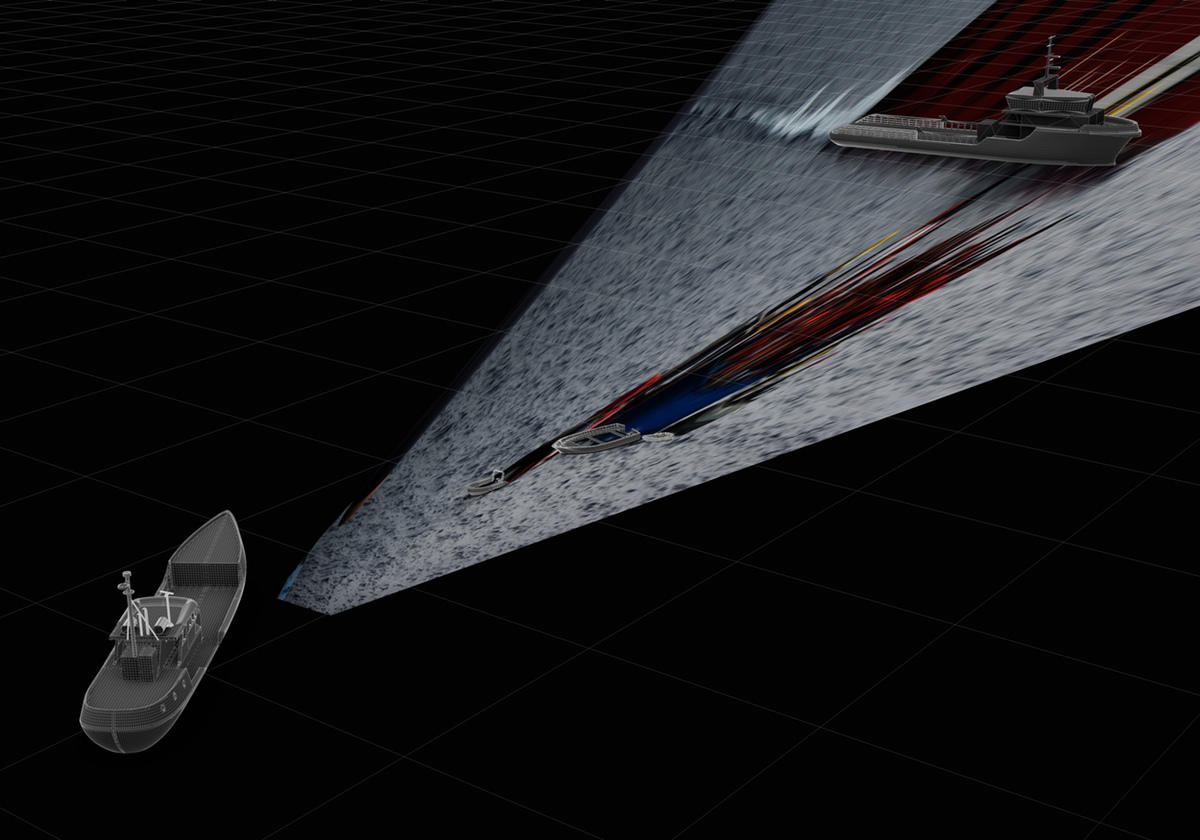

Image: Forensic Oceanography and Forensic Architecture, 2018

This kind of flagrant disregard for truth clearly worries Weizman. “When you attack the truth in this way,” he tells me later, “usually also you attack people. These forms of violence, violence against bodies, violence against truth, violence against people, are completely entangled.” Though “propaganda has always existed”, Weizman believes we are entering a dark new era in which there is “an attack on the very possibility of truth”.

“When you attack the truth in this way, usually also you attack people.”

Forensic Architecture staged a meticulous reconstruction contesting Temme’s claims at the arts festival Documenta 14 in Kassel, which was eventually seen by German members of parliament and by members of the police investigating the incident––as a result they were asked to restage their work for the benefit of both the politicians and the authorities, and the enquiry into the case, over a decade old, took on a new energy. This sort of crossover, switching between forums like the International Criminal Court and the Venice Biennale, aiming to apply cultural pressure as well as legal, is part of Forensic Architecture’s method.

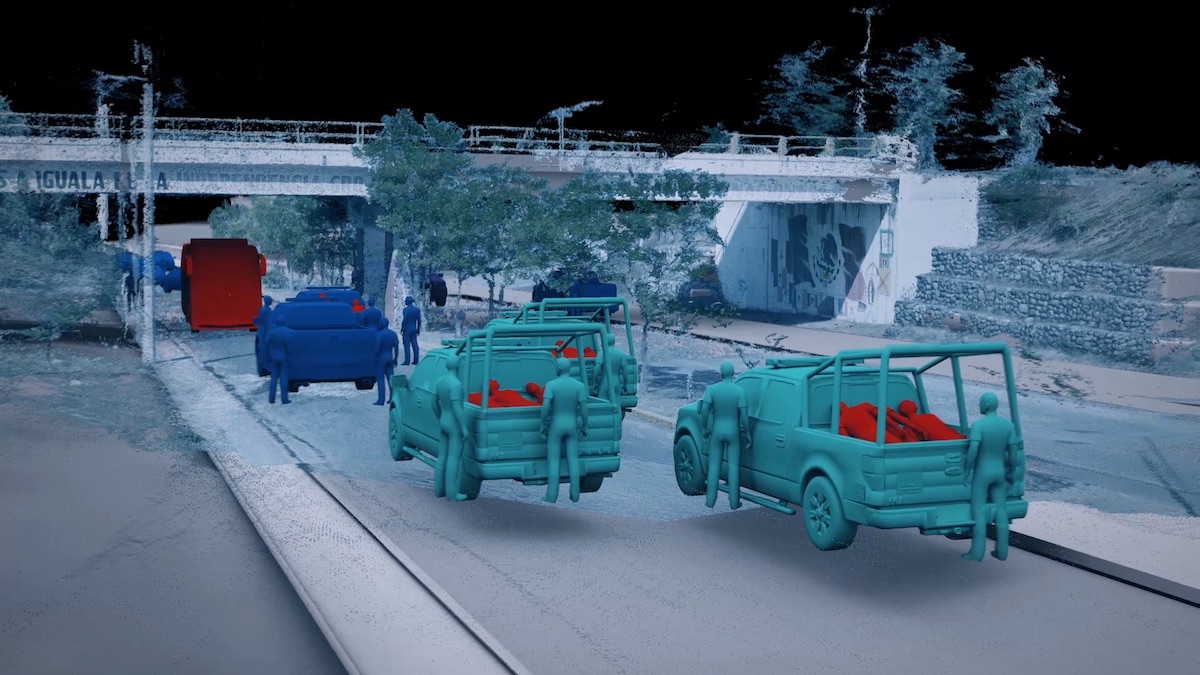

Image: Forensic Architecture, 2017

The agency sprang from Weizman’s early work in Israel and Palestine. In a study that was commissioned and ultimately suppressed by the Israeli Association of United Architects, Weizman, who did his PhD at the Architectural Association, convincingly argued that professional architects, and the aggressive use of architecture and infrastructure, played a very active role in the occupation of Palestine (the study was finally released in 2003 by Verso under the title A Civilian Occupation). Weizman went on to publish a slew of books and studies, including a vertiginously bizarre article based on interviews with Israeli army officers who claimed to have absorbed the teachings of Deleuze, Guattari and Guy Debord in their “postmodern” approach to urban military operations. (Derrida was “a little too opaque for our crowd,” admitted Brigadier General Shimon Naveh to Weizman.)

Photo: Mark Blower

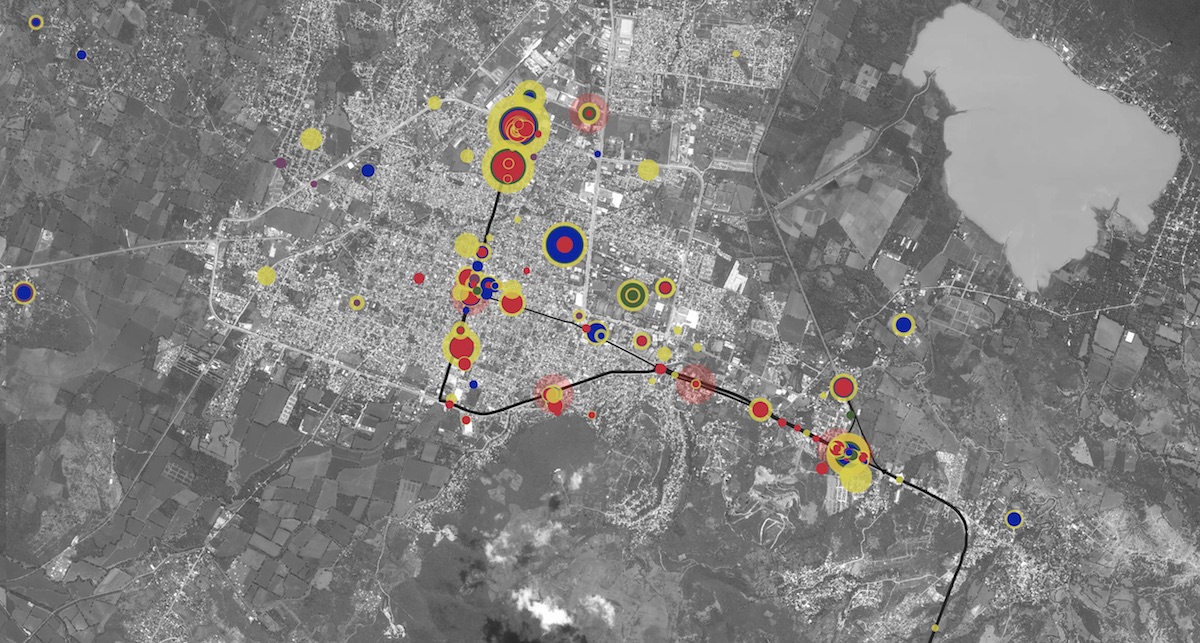

After this work Weizman founded Forensic Architecture in 2010, and the agency has now conducted investigations all over the world, in Guatemala, Indonesia, Palestine and Mexico, but for this show at the ICA their focus is on Europe and the UK––particularly the disappointing reaction to the refugee crisis, both by governments and by a wider political culture that is proving a fertile incubator for right-wing extremism, such as that which claimed the life of Yozgat.

“Because of where we are right now politically in Britain,” says Weizman, “particularly this space and time, we wanted to show where refugees are coming from, and show, when people are living here, the political violence that is inflicted on communities.” Christina Varvia, research coordinator at Forensic Architecture and co-curator of the exhibition, agrees: “It was important to look at ourselves, to self-reflect.” Varvia wants visitors to consider the “inherent violence, the infrastructural violence, that exists in countries such as Germany or the UK”

“Truth is what holds us together, like an understanding of the world as it is. Of course it is continuously corrected and under construction.”

To this end, the exhibition is focused on educating a British audience about the horrific reality of the kind of violence that people are fleeing from in Syria, through a study of a secret torture prison called Saydnaya, and then a detailed series of films picking apart the chaotic and deadly “rescue” provision facing them when they try their luck across the Mediterranean sea, subject to EU policies that “are themselves designed with a kind of death ratio in mind,” as Varvia puts it.

Image: Forensic Architecture, 2018

The message is certainly timely––in fact as I write up this article a new report about the UK immigration detention system has found that it continues to lock up and retraumatize people who, by the Home Office’s very own definitions, are victims of torture and so should not be detained. For Weizman the only defence against such bold-faced official inconsistency is public, active projects engaged in the production and demonstration of truth. “Truth is what holds us together, like an understanding of the world as it is,” he tells me. “Of course it is continuously corrected and under construction; it is like a construction site, it takes work to do it, but there is a common dimension to it. It holds a common idea of living in the world together.”

Counter Investigations: Forensic Architecture

Until 6 May 2018 at Institute of Contemporary Arts, London

VISIT WEBSITE