I cried when I heard of the death of David Bowie. I have spoken about this gut reaction with many others who did the same, trying to place our intense feeling of loss––most, like me, had never wept at the passing of a celebrity before. For all of us, his music connected to a deeply personal set of memories, ambitions, fantasies and freedom, at once shared and entirely our own. Ten months after his death, I sat in the darkened Barbican auditorium to immerse myself in To A Simple, Rock ‘n’ Roll . . . Song.

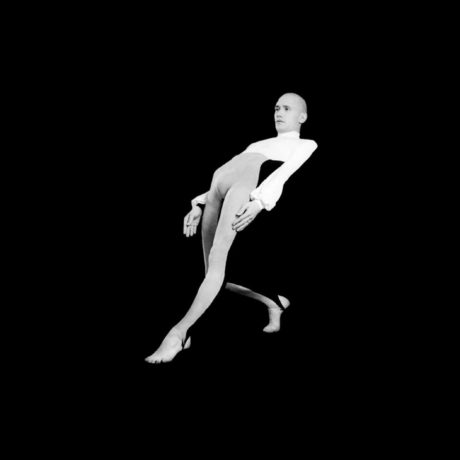

Created and choreographed by Michael Clark, the dance performance ends with a tribute to Bowie that moves from frenetic uplift to stark melancholy. Dancers in shiny silver suits stretch and slide to Blackstar, the valedictory title track of his final album, shimmering amidst the darkness. With the music playing at full volume, I am transported away from the packed-out room, held up with collective ecstatic mourning. This ability to not just transform pain into joy, but to encompass the two in a single motion, is the magic of Michael Clark.

An icon of British dance, Clark has always brought together contrasting worlds. After making a name for himself at London’s Royal Ballet School, he entered the punk scene of the 1980s. Wild performances with the likes of exuberant artist and club promoter Leigh Bowery (notably a model and muse to Lucien Freud), and partnerships with such artists as Sarah Lucas and Peter Doig, challenged the conventions of ballet, and suggested that it had a place in the seething real-life underground of London’s counterculture. Mark E Smith, another musical icon who passed away two years after Bowie, was also a collaborator.

In To A Simple, Rock ‘n’ Roll . . . Song, legendary video artist Charles Atlas is on hand to direct the high-contrast colours and moving image projections, having designed lighting for Clark’s performances since the 1970s. A soft orange glow opens the performance, before giving way to an almost over-ripe purple, as dancers cut stark shapes against it in simple black and white costumes and bare feet.

“This ability to not just transform pain into joy, but to encompass the two in a single motion, is the magic of Michael Clark”

The performance is divided by its three highly distinct musical choices. Opening with Erik Satie, the composer’s piano works are animated by dancers who hold themselves with rigid poise. Their movement is stripped-back and minimal, their poses held at length as if they were part-human, part-sculpture. Patti Smith’s Land takes over next, and the dancers return to the stage with new swagger and sway. Their tight monochromatic outfits have loosened to leather flares, which swing lightly as they leap and thrust their hips back and forth. It is an awakening, with all the allure of early rebellion.

The gesture takes me back to my teenage days, lost in the down-to-earth voice of Patti Smith, longing for the assertiveness that adulthood could bring while wishing away the tightening grip of responsibility. Dancers entwine with one another onstage, coupling in carefree moments before kicking away suddenly and dreaming of more. The backdrop is Charles Atlas’s video installation Painting by Numbers adapted for the stage, a tumbling array of white numbers that shower overhead.

David Bowie is kept for the final act. The dancers appear in their silver costumes, like molten metal moving through the air. Blackstar builds into the joyous energy of Aladdin Sane and the stage becomes thick with rapid motion, as if gleaming rain were falling from the sky above. Clark’s tribute to Bowie feels intensely personal, finding light in the darkness of his absence. This is a show that reflects life’s surprising contrasts, moving from sadness to joy in an instant. Like Bowie’s ability to connect with his audience on a highly personal, human scale, Michael Clark’s To A Simple, Rock ‘n’ Roll . . . Song shows that intimacy can be found in the collective pleasure of the performance.

All photographs by Hugo Glendinning