Immediately to the left of my desk is a window. When I’m bored or tired or feeling nosy, I look out of this window. I’ve learned a lot about my neighbours this way and imagined much about their lives since March last year. There is the woman who argues with someone on the phone at the same time every day, walking below my line of sight with her voice raised; and there is the little girl who scoots happily along with her mum but dawdles and complains when with dad. I recognise the vans of the delivery drivers who service my area, ferrying yet another parcel to people with the privilege to stay inside.

If I’m not looking out of the window, I’m on my phone. My concentration is so completely shot that any work I manage is done in a fugue state between long and intense bouts of procrastination. Through my phone I look at other people at home doing things that mostly aren’t work either. Sometimes my phone shows me memories that are now surreal: ‘1 Year Ago Today’ I was in a pub, or at a party, or with my family. They are a window to the past and a faraway future. Soon these archived digital memories will show me pictures from the first UK Lockdown.

In cinema the ‘space-off’ is the area outside the visible frame of the shot, inferred from what the frame does make visible. Despite what the filmmaker chooses to show us we can choose to think about the room, the building, the landscape and the world beyond. As the anniversary of that first lockdown approaches, I have reflected on the work of four artists and their use of video to document the early peak of the pandemic. They let our new reality live in and outside of the frame.

“They document an experience in ways which feel just as liminal as those portals to the past on my phone”

From March to July 2020, director Orian Barki and artist Meriem Bennani made a series of eight films from in and around their New York apartment, while director Stroma Cairns was stuck inside a London flat with her mum and siblings for the first time in years, documenting their bouncing off the walls in her Quarantine series. In Lagos, filmmaker Munachiso Nzeribe was compelled to film out of her taxi window as lockdown began in March, gathering footage that she would work into a film three months later. The resulting works don’t attempt to make sense of the pandemic. Instead, they document an immediate experience of it in ways which feel just as strange and liminal as those portals to the past on my phone.

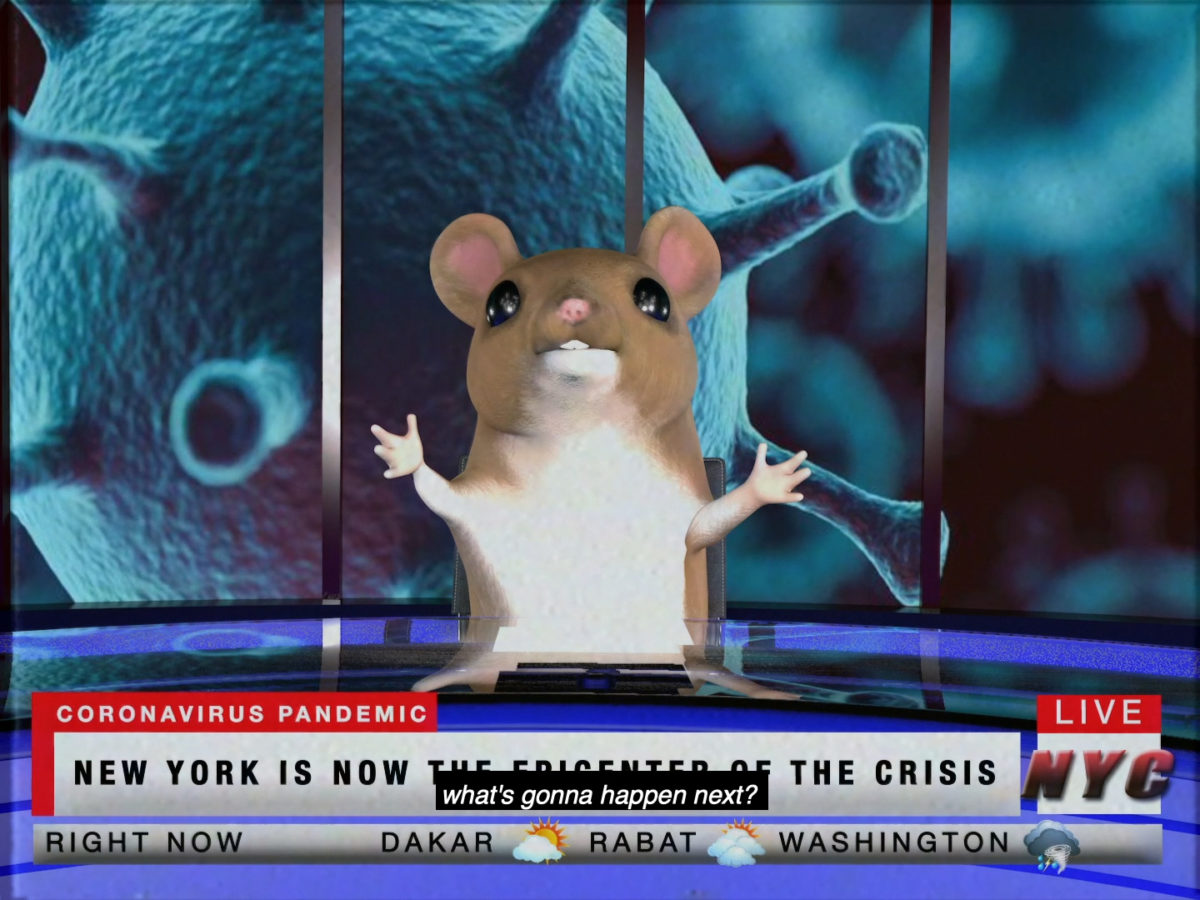

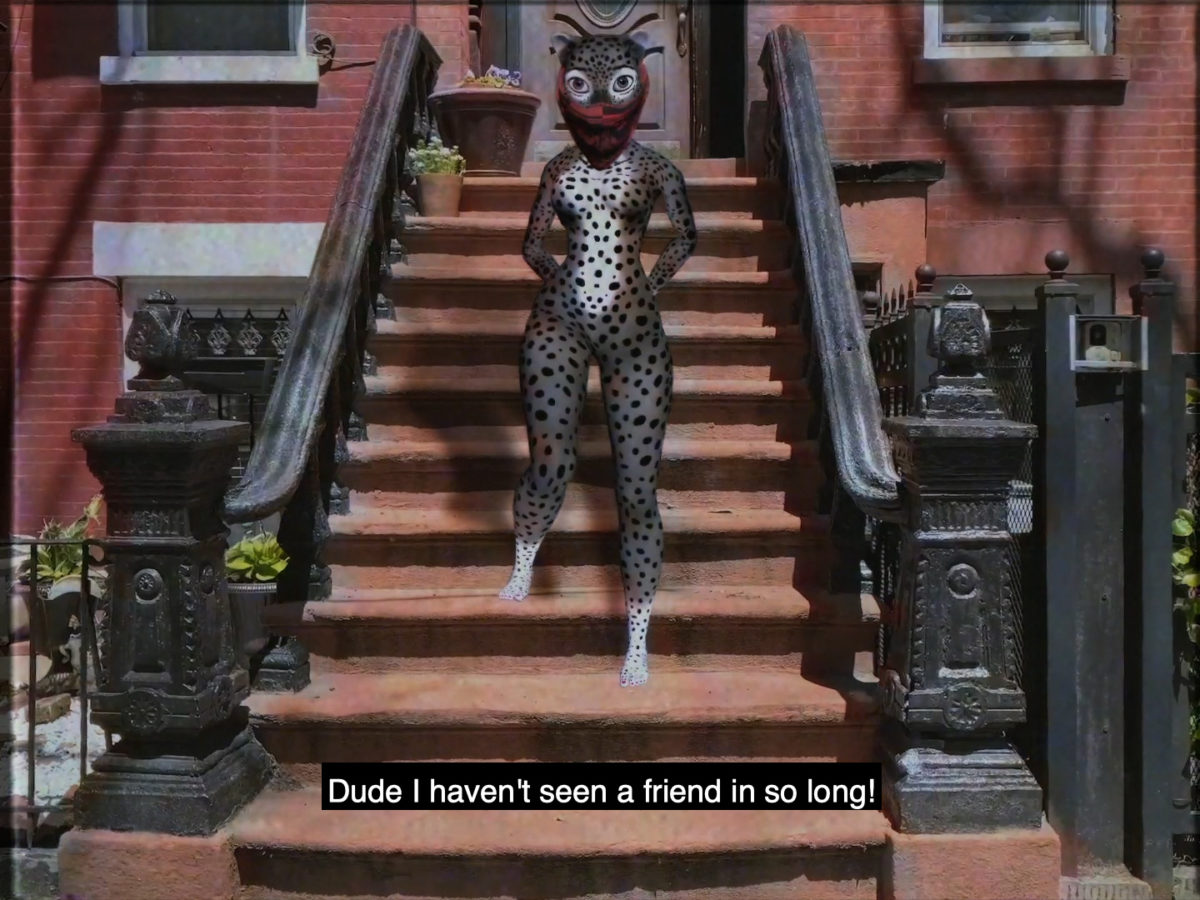

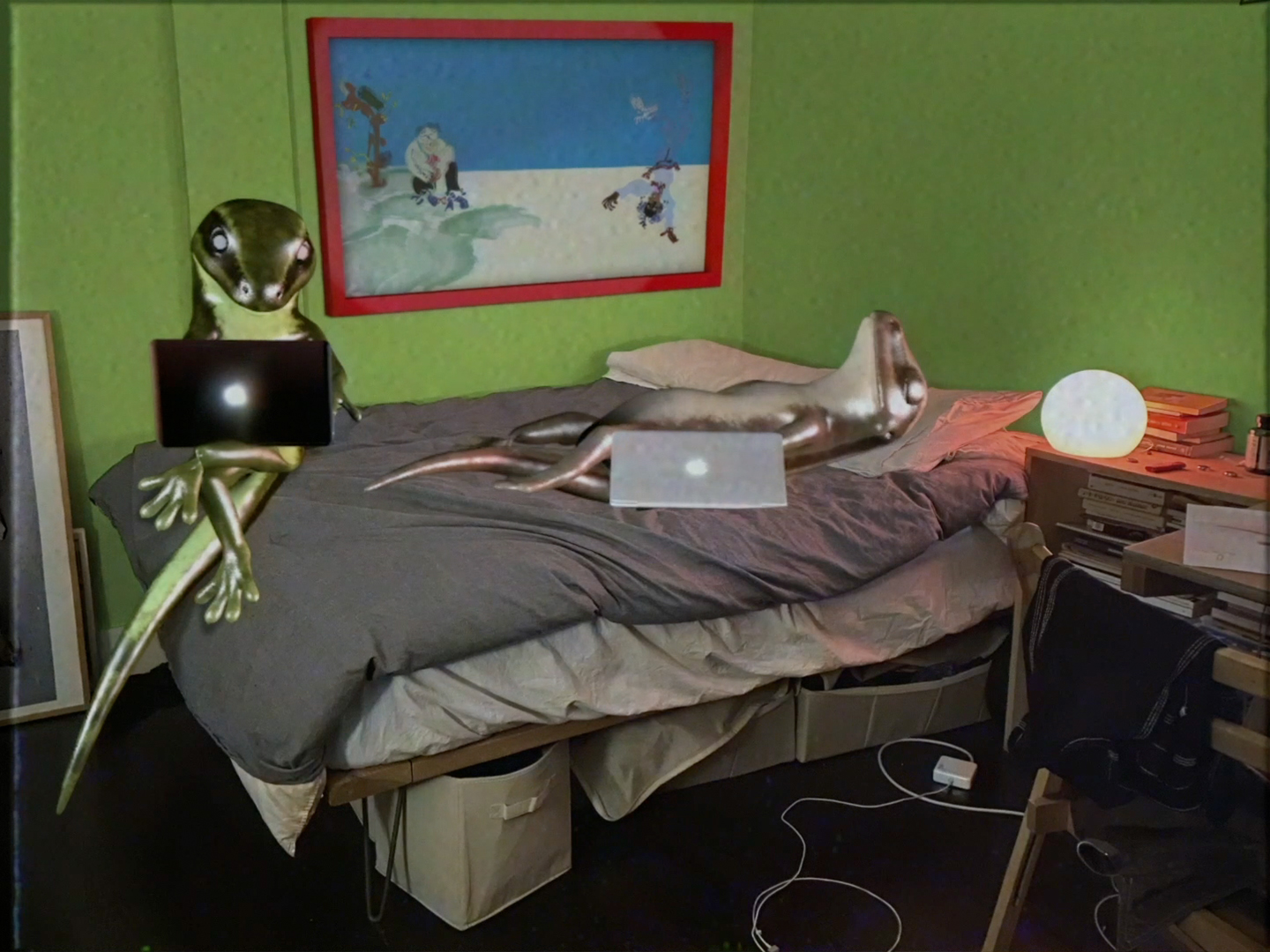

Barki and Bennani’s Two Lizards series uses 3D animation over background footage filmed in and around their apartment. The films slowly widen in scope to take in not just their rooftop but the city, the country, the world. “That was our natural process of experiencing the new reality of the pandemic”, says Barki, “first examining our own personal state and then looking at the state outside of our immediate perimeter.” The resulting cast of characters are warm and relatable, voiced in a highly naturalistic, half-improvised style—presented as animal avatars that successfully convey the full breadth of human emotion.

They talk and live in a way that is comforting in its familiarity. In one episode the lizards wander around an empty Times Square looking for somewhere to pee (“They really need to turn these billboards off,” they muse. “I know. They would never!”); while in another, a feline nurse recounts how people avoid her on the Subway for wearing scrubs, laughing at the irony as the 7pm clap for essential workers begins. Perhaps what makes these films feel so pure is that they were “created in real time”, rather than with any kind of hindsight. As Barki points out: “most of it was a natural reaction to reality.”

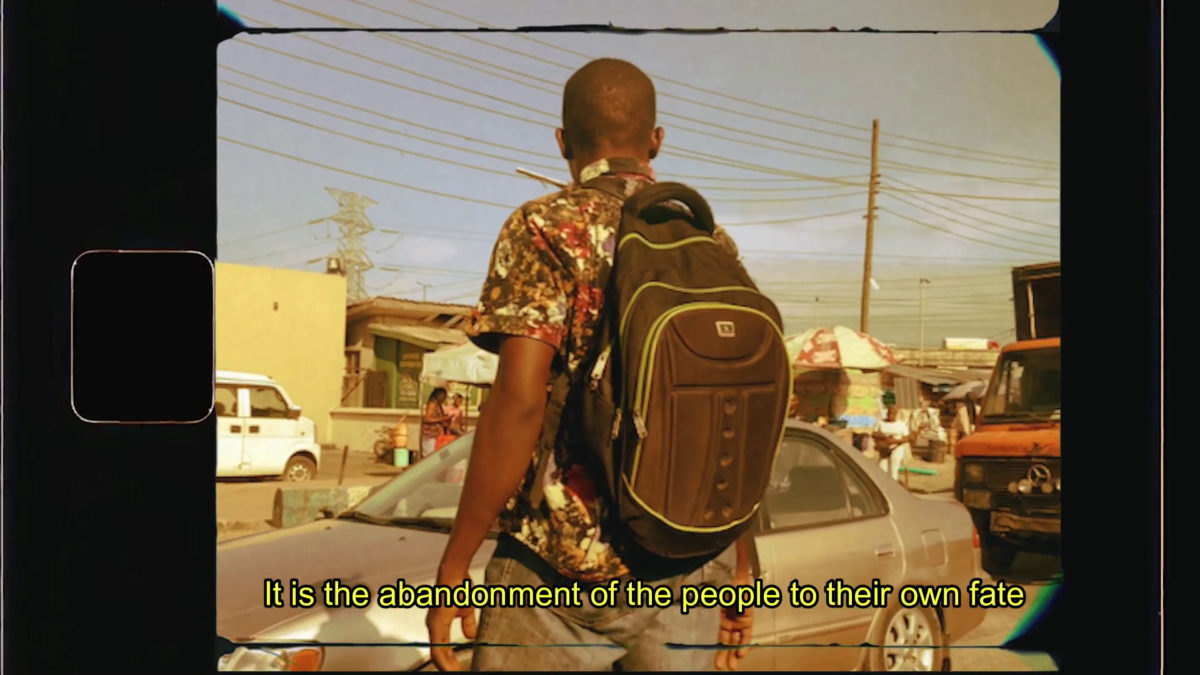

- Munachiso Nzeribe, Onyemaechi (still), 2020. Courtesy the artist

Nzeribe was likewise drawn to her subject without the strictures of a plan: “All the footage wasn’t necessarily intentional,” she says of making her film Onyemaechi (Who Knows Tomorrow?). “I just went with the flow of how I was feeling at that moment and created.” Onyemaechi was mostly shot through windows, often on the move, taking in the happenings not just of Nzeribe’s neighbours but life in other parts of Lagos too. Its focus is more explicitly political, pairing a voiceover of Nzeribe’s own thoughts with words from Nigerian activist and lawyer Dele Farotimi. “When are we going to eat the rich?” muses a title card.

From inside closed spaces like a taxi or her bedroom, Nzeribe’s film reflects on the sheltered privilege she enjoys as a middle-class citizen: “The window to me as an artist represents stepping out of your reality into other peoples lived experiences…In observing my surrounding there’s a clear dichotomy between the rich and the poor. Living in Lagos for me is definitely a very frustrating experience.” Nzeribe’s roving lens conveys that feeling of frustration at watching an inept government leave its people behind, the lens pausing to focus on a face as the taxi slows before being forced to zoom away. “I’ve always been a keen observer,” she says, “but I definitely feel like isolation made me a more intentional observer.”

- Stroma Cairns, Quarantine (still), 2020. Courtesy the artist

The pandemic has made keen observers of us all, encouraging us to monitor our fellow citizens and ourselves more closely than ever. Time has also taken on a new strangeness, void of the usual markers and events that help give it shape. Lockdown kept London-based Cairns in one place, and suddenly all she could watch was her own family: “I kept trying to start new projects but was getting distracted by how chaotic it was living back at my mum’s.” Eventually she gave in to the chaos and chose to focus all that energy into making something: “my subjects were constantly around…to be honest it was the most freeing creative process.”

Cairns’ films capture the very specific feelings that erupt when you’re stuck with the people you love; they feel more like emotional snapshots than documents of any event or happening in particular. Cairns keeps a tight lens on her family, zooming in on their tears, screams or laughter with a focus that feels not invasive, but intimate. “People I didn’t know would DM me saying it really made their day,” says Cairns. Her films do foster a real sense of connection. You squeeze onto her family’s tiny balcony to sunbathe, or huddle round their kitchen table as they argue, feeling more like part of the furniture than an outside observer.

Each of these artists have made work in the midst of a crisis as a way to find a foothold in it. Barki reflects that the films “helped to pass the time, process reality, feel connected, have a sense of control over what was happening.” Looking back, though, she also sees a naivety there, which is perhaps what makes watching the films now so tender: “the first wave was more saturated, everything was new: the lizards are definitely a representation of that feeling, they are romantic and youthful in their fascination.”

“They let our new reality live in and outside of the frame”

In contrast, Nzeribe’s film is a study in frustrated time: a “manifestation of the phrase who knows tomorrow?” She gave the film a deliberately dated feel to visually represent that sense of time gone stagnant: “I wanted to reflect how Lagos hasn’t really changed structurally or systematically over the years.” Looking back on her own work has a temporal strangeness for Cairns. “It literally feels like yesterday, and makes you feel like time hasn’t moved at all.”

The space-off of a social media post is often much harder to piece together than in a film; our feeds wilfully obscure so much of reality. All of these films were posted through Instagram first (although Nzeribe’s lives on YouTube). Barki and Bennani explain that they deliberately chose to give their films an accessible home: “We made them as an independent project and weren’t interested in trying to find a platform that would want to feature them.” Likewise, Cairns sought to undermine the usual artifice associated with the platform: “Instagram can be a depressing, weird space sometimes, so I thought it would be nice to just put something out that was more honest.”

To bump up against these films amidst a bout of doomscrolling is a welcome intervention. They felt at home on my phone while simultaneously helping me to peer into something beyond it. Months later they still retain that intimacy and immediacy, like an open window just beside you.