What is Awaaz?

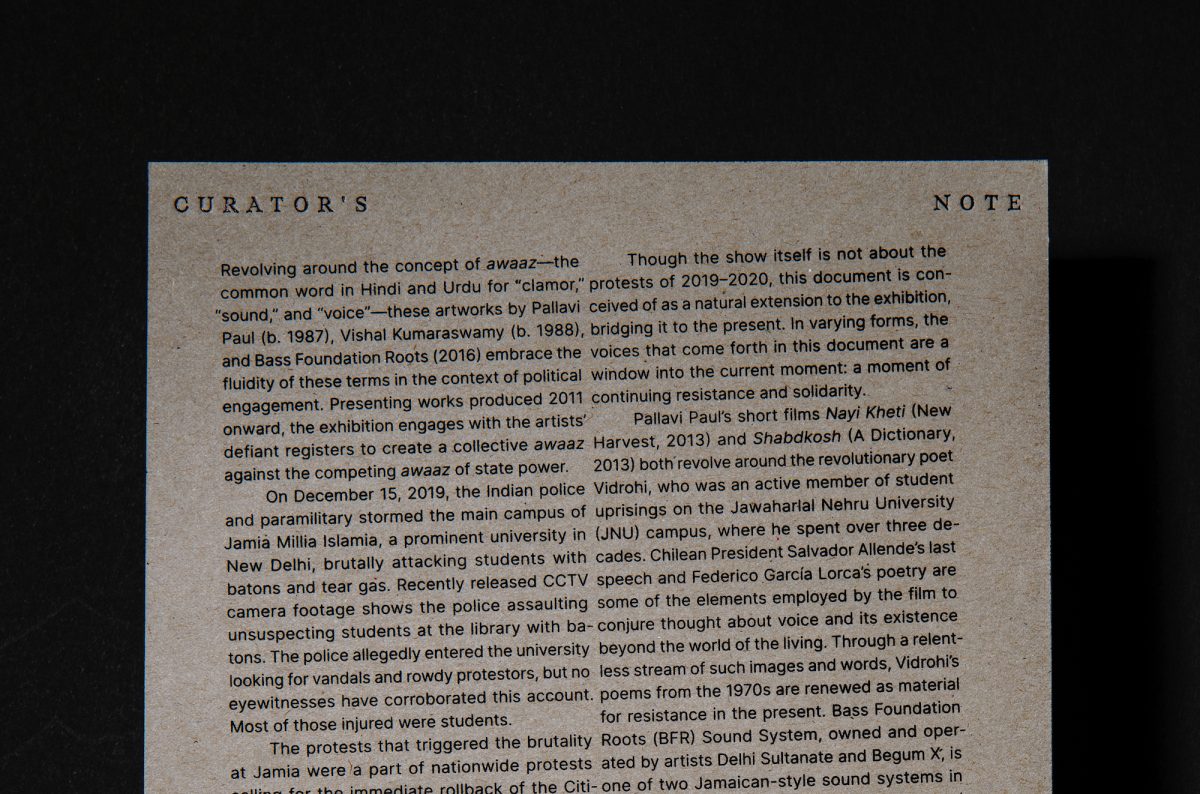

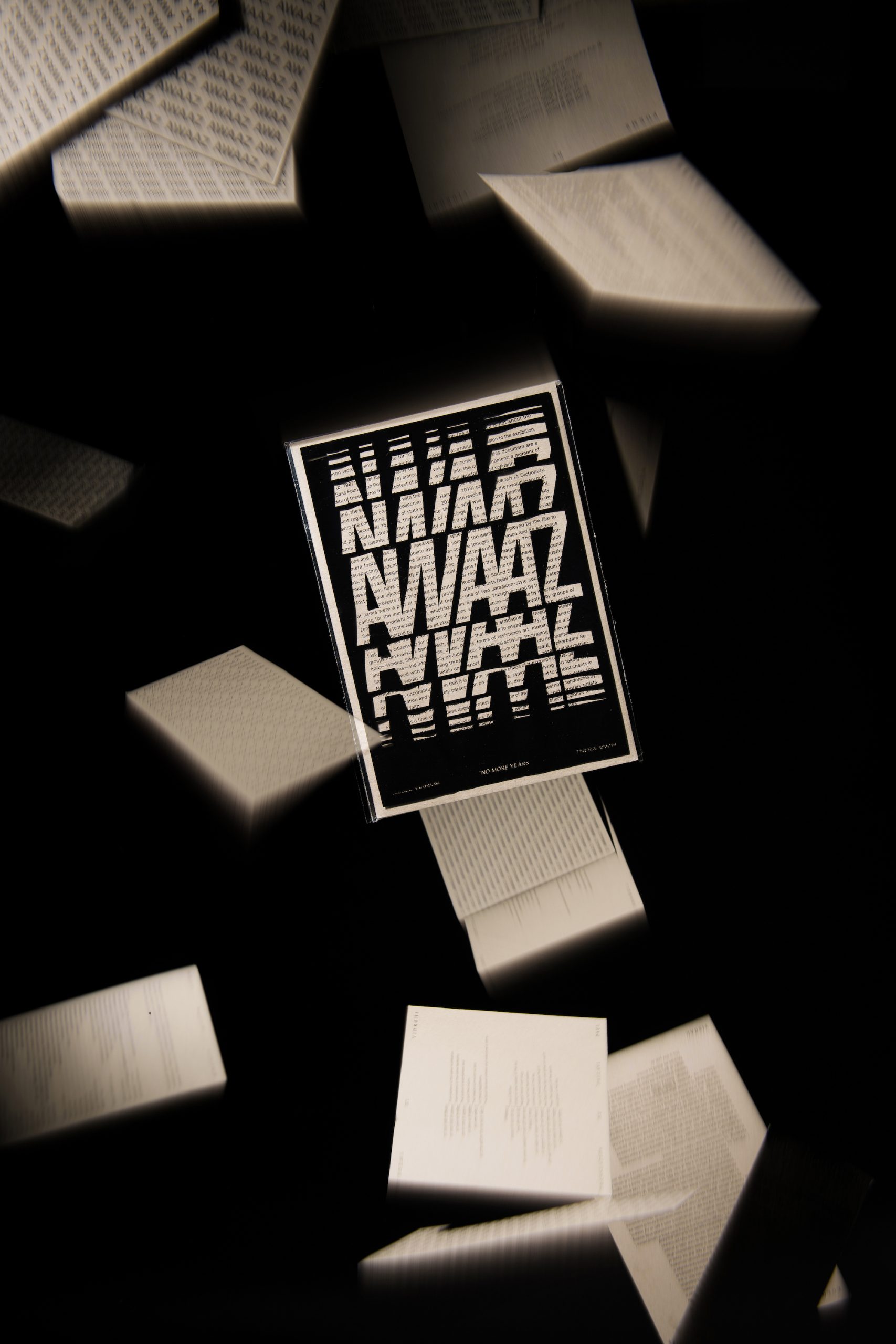

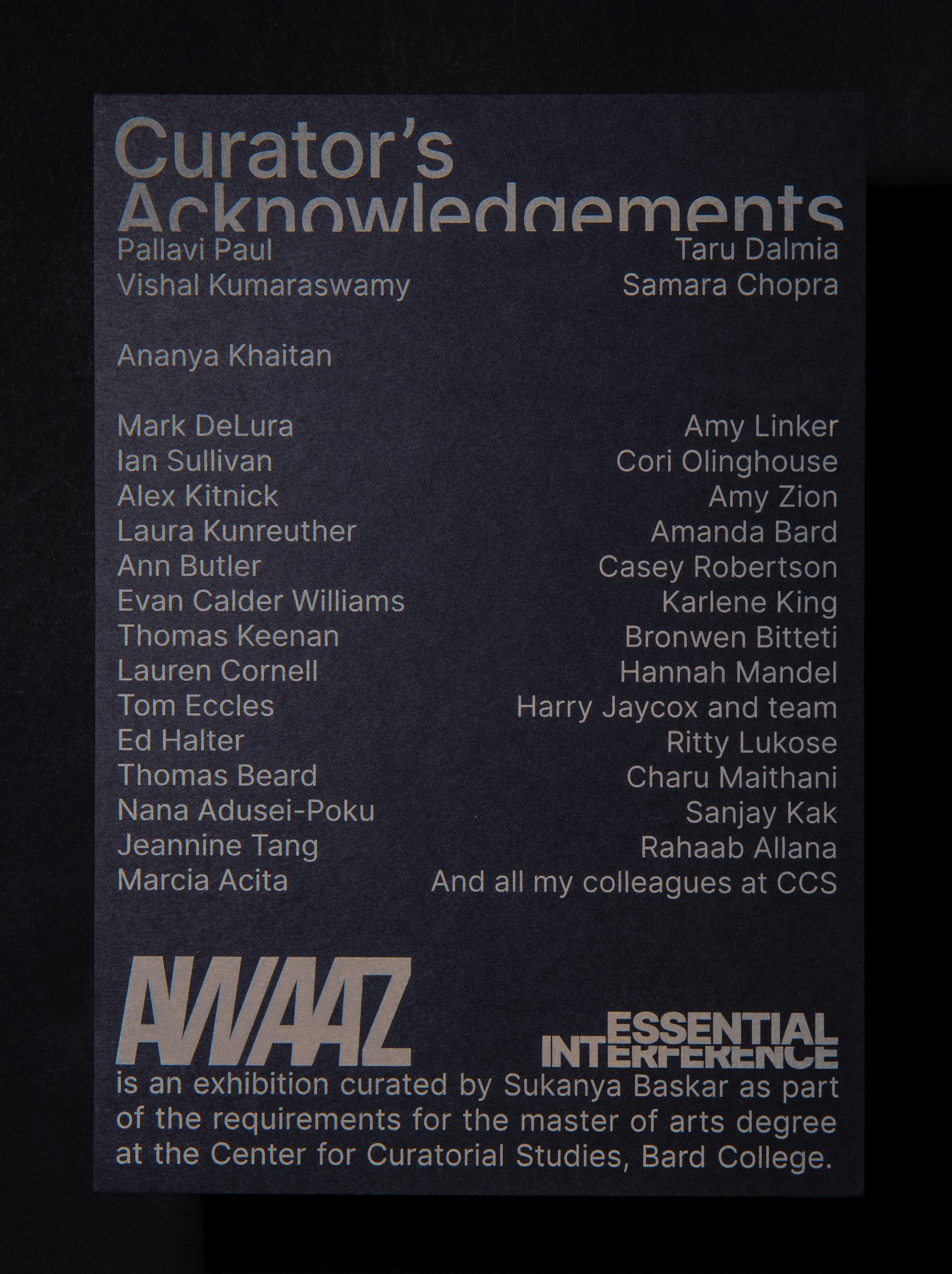

Curated by Sukanya Baskar at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College in upstate New York last year, the exhibition Awaaz (which translates to “voice” or “noise” from Hindi and Urdu) and its accompanying publication feature texts responding to the rise of fascism in India. While it was being put together and designed in 2020 by the New Delhi-based graphic designer Ananya Khaitan, protests against the CAA/NRC laws were breaking out across India, with protestors opposing discriminatory government policies that targeted non-Hindus, especially Muslims. “Given the spirit of the exhibition, the publication took a left turn, pun intended,” says Khaitan. “All the featured artists from the show submitted textual pieces (poems, eulogies and such) and the resulting document became a time capsule of that tumultuous moment.”

“Artists are a valve through which societal rage is expressed, as well as a balm which eases the pain”

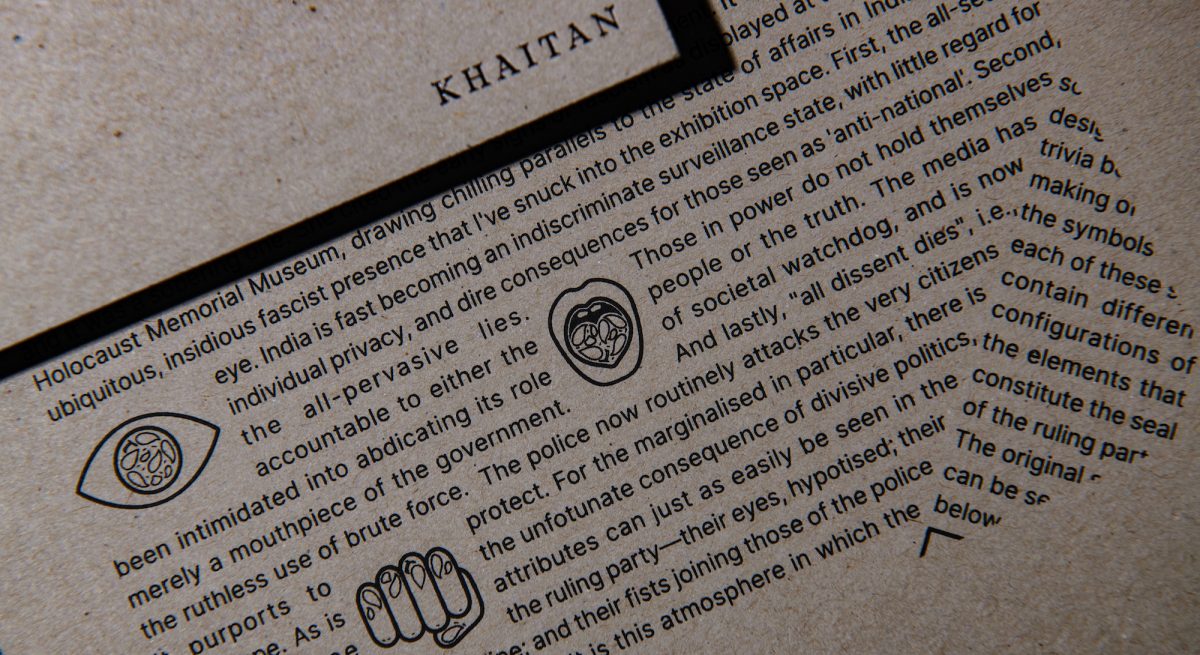

The typefaces of the publication echo the reverberating sounds that collective voices create, forming graphic interjections and repetitions evoking calls and chants. “It’s the ‘awaaz’ of unrest, of protest,” continues Khaitan, who selected open-source typefaces to chime with the collective nature of the book’s message. Inside its loose pages, readers will find poems by Ramashankar Yadav, also known as Vidrohi, submitted by video artist Pallavi Paul. “The famed poet and social activist studied at Jawaharlal Nehru University, the liberal arts university often targeted and scapegoated by the government,” explains Khaitan. “Also, media artist Vishal Kumaraswamy submitted an Eulogy for Broken Relationships, an excellent piece describing a fairly universal experience during such polarised times, that of discovering shocking and irreconcilable political differences with loved ones.”

Who’s behind it?

As was the exhibition, the zine was conceptualised by curator Sukanya Baskar. Far away from her home country in America and unable to travel into India due to the pandemic, she felt compelled to engage with the politics and tumult of that particular moment, choosing an exhibition and print to do so. She and Khaitan discussed the exhibition and publication’s graphics remotely. The international nature of their collaboration, along with that of the artists involved who were also scattered across the world, prompted the decision to design the book as separate sheets taking different formats.

“These sheets were rough-hewn textured card-stock, echoing the sombre nature of the content,” explains Khaitan. “These are double-pasted, to give each some heft, with the edges treated with black. The entire publication is screen-printed, except for the page titles and author names, which were stamped onto the page.”

Why else should I read it?

“The zine feels almost quaint at this moment in time, given how the pandemic is ravaging India and the government’s wrongdoing and neglect has far surpassed what even its worst critics could have expected,” says Khaitan. That said, what he hopes readers could take away from the publication, apart from some insight into what’s happening in India, is the vital role that artists and artists’ voices play during difficult and troubled times: “They are a valve through which societal rage is expressed, as well as a balm which eases the pain.”