“Like they say, ‘You’ve never seen a man cry until you’ve seen a man die,’” reflects Jammie Holmes. At just 37 years old, the Dallas-based artist has felt the leaden touch of grief more than most. His figurative paintings capture contemporary black family life in the Deep South, meditating on ritual and tradition as well as darker themes of suppression and fear in disenfranchised communities. Holmes offers a layered view of black masculinity: his paintings are vulnerable tributes to the people he’s loved and, in some cases, lost. One poignant work, Living in the Shadows, portrays a man conflicted about his own sexuality and at the end of a lifelong journey for self-acceptance.

“I had been through so much growing up and I wanted to get rid of my anxiety. I just needed to paint”

More recently, Holmes garnered international attention last summer when he committed George Floyd’s final words to the sky. Small planes flew over a handful of US cities, banners billowing behind them emblazoned with Floyd’s chilling pleas: “Please I Can’t Breath”, “Everything Hurts”, “They’re Going to Kill Me”. “When George Floyd died, I was able to be more calm about the situation because I know what it’s like. I’ve been pulled over by police before, I’ve been searched before, I get all of that,” says Holmes measuredly. Yet the artist is far from apathetic: “It’s not that I’m less sensitive to it. I just handle it differently.”

Much of Holmes’ work is rooted in his upbringing. The self-taught painter grew up in the heart of Louisiana in the city of Thibodaux, south of the Mississippi River. His family lived on Narrow Street, a mile-long road of modest, low-slung homes. The street itself is a tapestry of closely-knit families occupying neighbouring homes. But behind its unassuming façade lies one of the deadliest moments of US labour history: Narrow Street is located in the same neighbourhood where the 1887 Thibodaux Massacre took place, in which tens of striking black sugar cane workers and their families were killed by a mob of white militiamen (the true number of fatalities remains unconfirmed).

“No matter how many times I watched my mom smile, I watched her cry a hundred times more”

Thibodaux has been scarred by decades of racism, violence and poverty. And like many Southern cities, it has been reluctant to face a reckoning with its poisoned past. It took until 2017 for the local city council to formally acknowledge and condemn the massacre. “There is so much blood on Thibodaux soil,” says Holmes, noting the prevalence of plantation houses in the area. “We’ve had Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Isaac, Hurricane Andrew… all these big hurricanes and these slave quarters are still standing.” Holmes himself is only four generations removed from slavery in his own family: his great-great-grandmother was born a slave.

As Holmes recounts his past he often returns to the women in his life. “All the women in my family raised their kids by themselves: my grandmother, my mom, my aunt,” he says. “That’s what shaped every single man in my family, because we were all raised by women. They taught us the good, they taught us the bad, they just taught us how to be men.” Holmes credits his mother with being his “crutch” when he first moved to Dallas. In Mama Raised Me (2020), she’s depicted as a confident, beaming figure clad in a glamorous red dress. But even as Holmes reconciles with his childhood, using his paintings and undertaking therapy to heal, the trauma still lingers. “No matter how many times I watched my mom smile, I watched her cry a hundred times more.”

Holmes didn’t set out to be an artist. In fact, he had been working for years in Louisiana oil fields when a position opened up at a machine shop in Dallas. “I took a chance and lied on my application because they needed somebody local,” he recalls. “I gave them a random address and they gave me the job. They wanted me to start the next day so I had to go to Walmart to buy work clothes because I didn’t have them.” Holmes made the agonising but necessary decision to uproot his life and leave his family behind: “I had to sacrifice everything to take a chance to make something out of myself.”

“I need them to feel the painting, because I want them to experience what I felt when I was creating the art”

A revelatory visit to the KAWS show at The Modern in Fort Worth inspired Holmes to begin painting in earnest and he bought some supplies from Michaels, a local art store. “I had been through so much growing up and I wanted to get rid of my anxiety,” he says. “I just needed to paint.” It’s been a whirlwind five years since his first-ever visit to an art museum and he now counts musician Lenny Kravitz and Quality Music Control founder Kevin Lee among his collectors. Soon, the artist will be showing new and recent work at a solo exhibition (22 May—26 June) with Library Street Collective, the Detroit-based gallery he signed with last year.

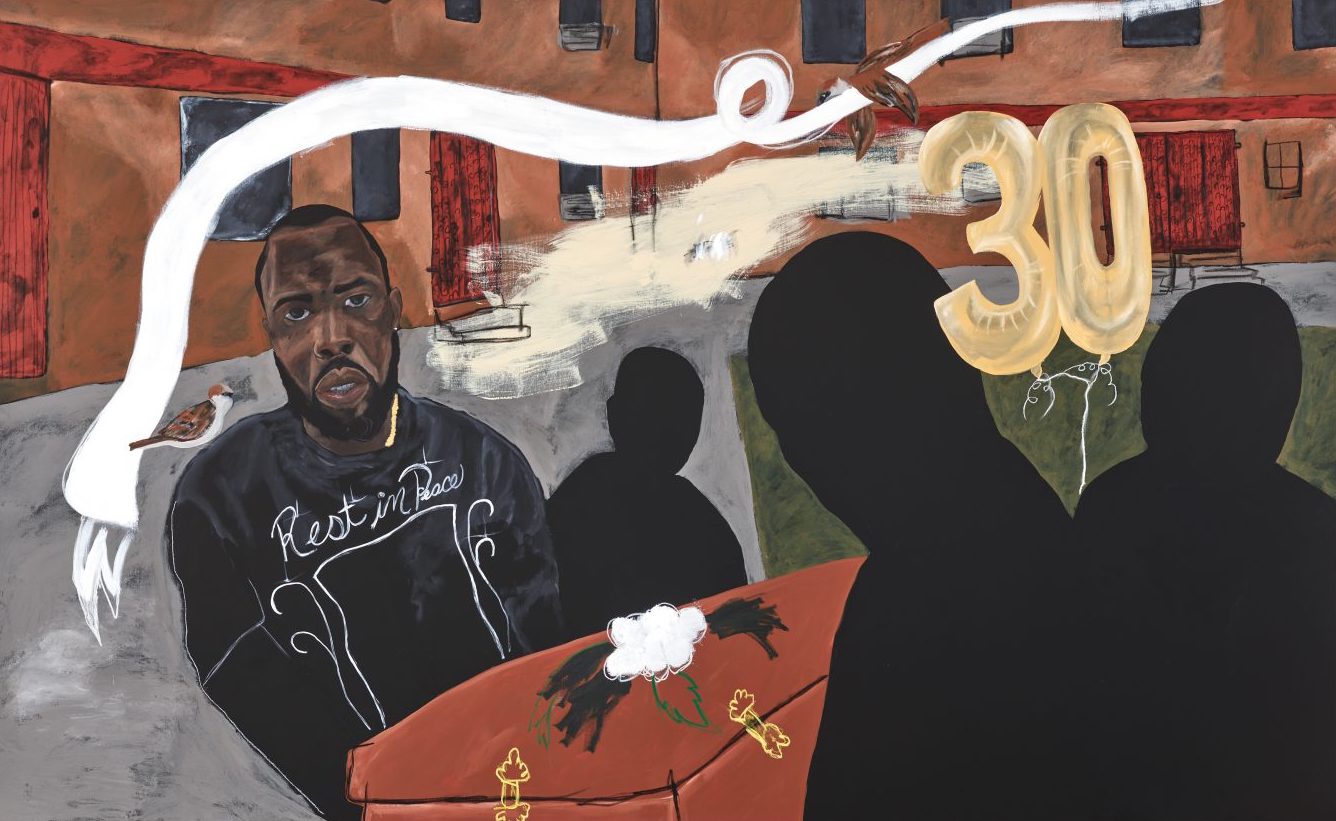

The show presents a narrative around the loss of someone close, an occurrence that is all too familiar for people who come from a neighbourhood like his, he says. One mourning ritual in Thibodaux involves making black T-shirts emblazoned with a portrait of their deceased loved ones and the words ‘Rest in Peace’. In past works, Holmes has included on these shirts an image of his cousin Tyrone, one of Holmes earliest and most fervent supporters until his death in a car accident. This time, however, the artist has left the shirts blank, allowing space for the viewer to imprint someone they have lost in their own lives. After more than a year spent in collective and individual mourning due to the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s an especially evocative invitation by the artist.

A number of the works illustrate an immersion in water, symbolising baptism. In Carrying Caskets #2, the artist depicts himself as a pallbearer carrying a casket through water, acting as the custodian at the boundary between life and death. “I wanted to show the feeling of an individual being a pallbearer to someone that they love, or really care about,” Holmes explains, having been a pallbearer to a close family member more than once. In each of the works that Holmes has painted himself into, he’s staring directly at the viewer: as he explains, “I need them to feel the painting, because I want them to experience what I felt when I was creating the art.”

Distance from Thibodaux has offered Holmes a new perspective. “Lately I’ve been listening to the buzzing of the lights in my studio. I don’t know why but it gives me time to clear my head and look at the pieces that I’m working on and to come up with new ideas,” says Holmes, who ‘paces’ his studio by riding his bicycle in circles. “I’m constantly planning what I want to do, I’m always thinking.” He’s determined to use his platform “to change the way the city is looked at” and to bring art to Thibodaux (Holmes is in the process of setting up a foundation). “I sometimes see it in a painful way, because I know how ambitious my city is,” he adds. “But I also know that they’re going to do whatever it takes to survive.”