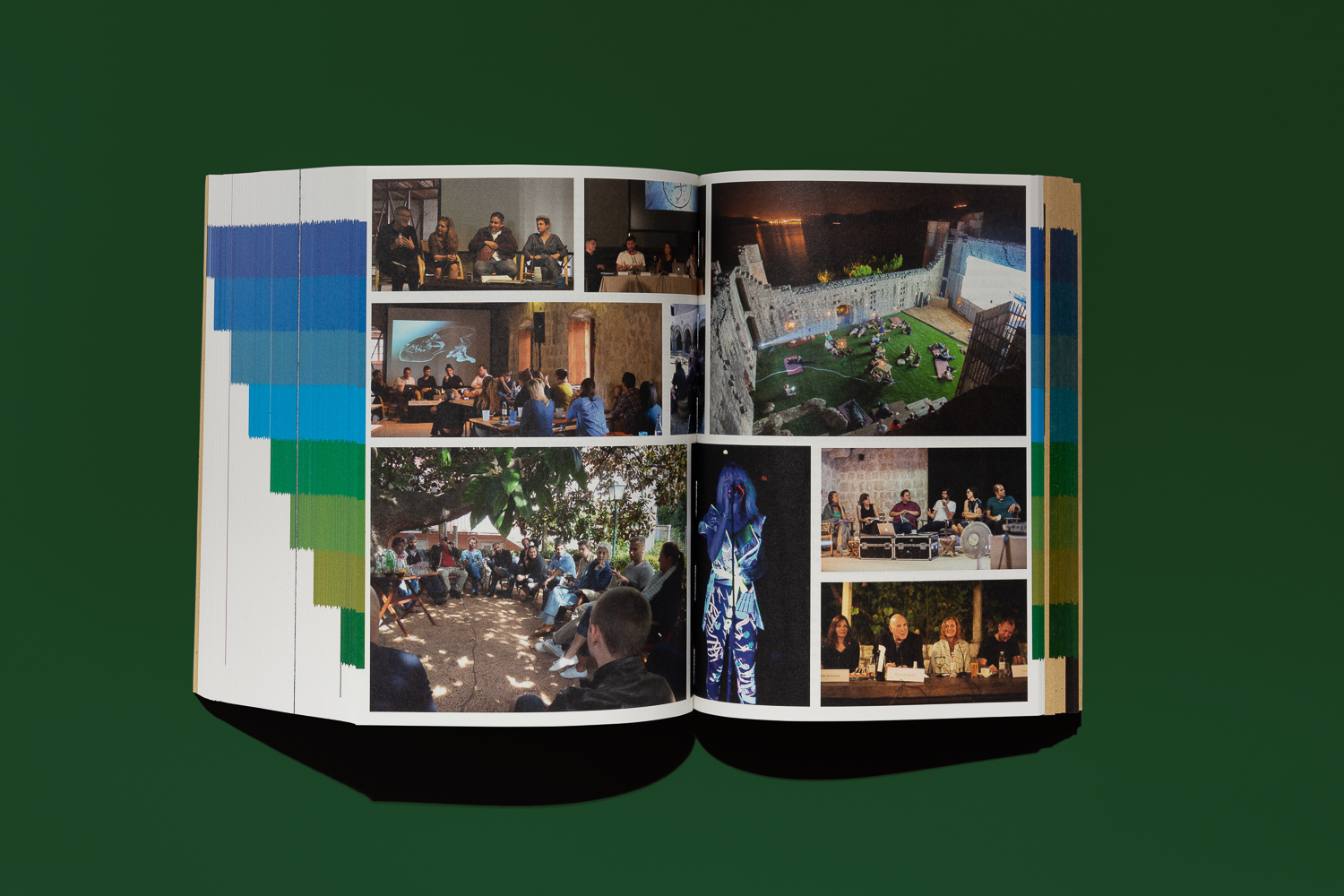

Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary: The Commissions Book, Sternberg Press

This brick of a book (it has over 1,300 pages) celebrates 20 years of experimental commissioning at the Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary (TBA21) foundation, featuring everything from sound installation to conceptual architecture, and an itinerant academy that takes place on a boat. With a dedication to supporting art that challenges our relationship to ecology and climate change, the list of artists and architects includes David Adjaye, John Akomfrah, Olafur Eliasson, Cecilia Bengolea and more. Within the 100 percent recyclable pages, you can expect to find in-depth interviews with the creators in question, alongside essays from transdisciplinary feminist theorists Astrida Neimanis and Eva Hayward. (Holly Black)

- Mark Mcknight, Heaven is a Prison, courtesy of the artist

Heaven is a Prison, Mark McKnight (Loose Joints)

Bodies tumble and entwine in an otherworldly desert landscape in photographer Mark McKnight’s latest book, the recipient of the 2020 Light Work Photobook Award. Shot in austere, high-contrast black and white, the sensation of the fantastical is heightened. The formal qualities of the human body are overlaid with those of the surrounding landscape, as naked limbs are contrasted with the arid grass, rocks and shrubbery. Nature is shown as boundless and yet curiously claustrophobic, and intimacies play out upon its all-encompassing terrain. Described by McKnight as a “queer purgatory”, there is an inherent tension at play between freedom and liberation, violence and affection, with no beginning or end in sight. (Louise Benson)

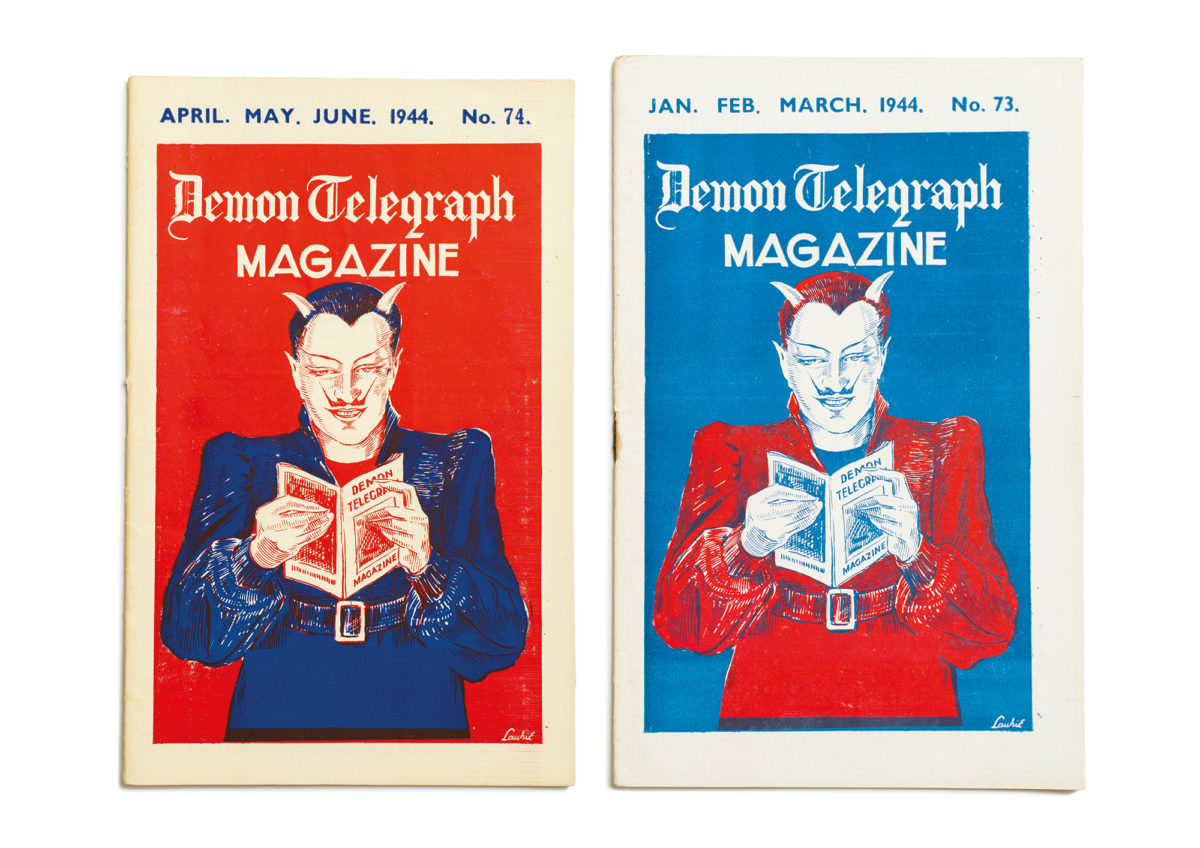

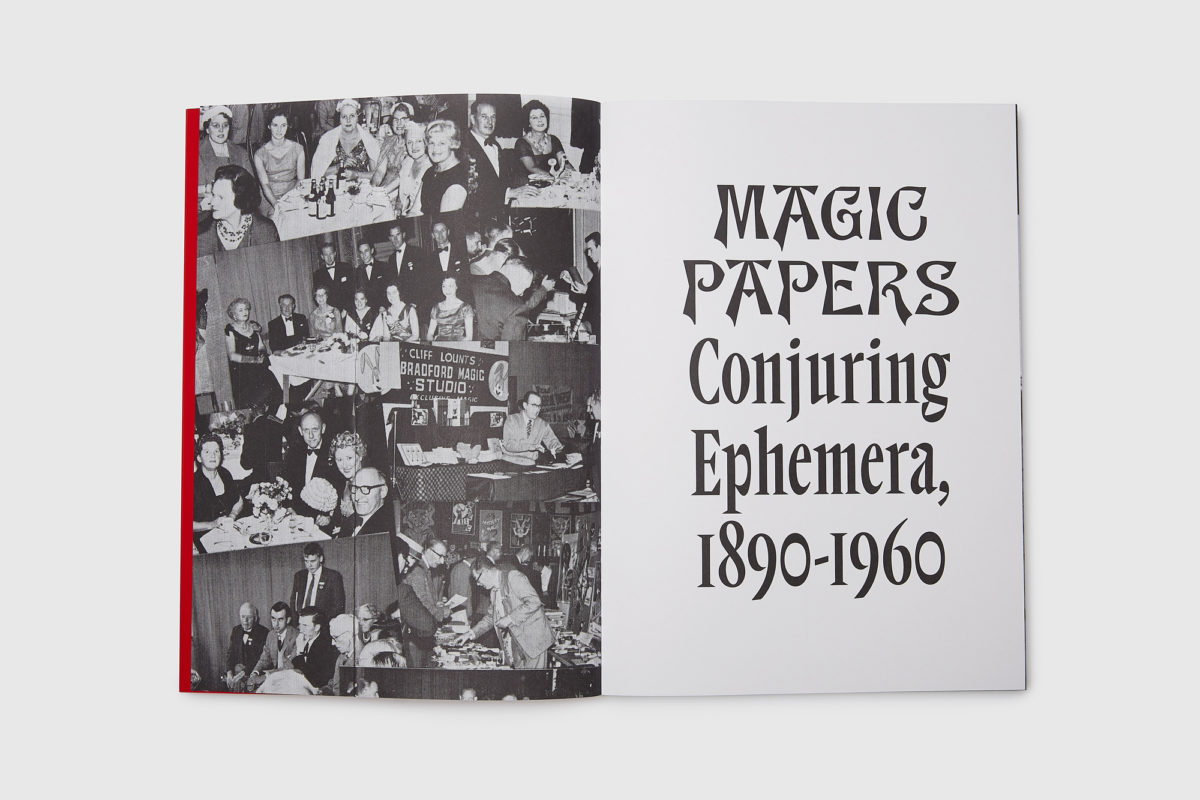

Magic Papers, Patrick Fry (CentreCentre)

Designer and publisher Patrick Fry and his publishing offshoot CentreCentre has a knack for making the seemingly dull interesting, and for unearthing the interesting things most would miss. The indie imprint is behind books including a genuinely intriguing tome about bricks, and another about the computer punchcards that were once ubiquitous but are now obsolete data storage and processing tools. Their latest book, Magic Papers, examines the ever-intriguing world of magic through the often unregulated and rarely preserved papers that disseminated the secrets of this cryptic craft back in its heyday around 100 years ago. These papers are strikingly beautiful in their elaborate, intricate designs—the typography alone is beguiling. The book’s contents was assembled from magic expert and archivist Philip David Treece’s collection of journals, periodicals, books and other ephemera created for the magic community between 1890 and 1960. As ever with CentreCentre, the book’s design is a thing of beauty, with subtle quirks in type and layout that serve the contents perfectly, never overshadowing it. (Emily Gosling)

Afternoons, Jenna Westra (Hassla)

The subtle gestures of even the briefest of encounters are unravelled by photographer Jenna Westra. She uses staged portraiture to construct and observe casual interactions between her models, drawing out the dynamics that are built up between them before the lens. Westra uses snippets of text, vignettes and simple instructions to create these scenes between her subjects, who are often dancers, encouraging movement and touch. Props and garments interact with bare skin, emphasising the sensual interplay of textures. Westra’s models bend, crouch and embrace freely in scenes that feel more charged than ever in the age of social distancing. Westra’s first book, Afternoons, accompanies her latest exhibition at Lubov Gallery, New York, which runs from 27 September to 22 November. (Louise Benson)

Philip Guston: A Life Spent Painting, Robert Storr

A major retrospective on the work of Philip Guston has controversially been pushed back to 2024 this week over concerns about the Ku Klux Klan imagery that frequently appears in his work as part of his message on social and racial equality, something he was deeply concerned with his whole life. Most roads in contemporary painting lead back to Philip Guston, who is as influential in 2020 as he was in the 1930s when he started out as a muralist. He was a classmate of Jackson Pollock and a close friend of Philip Roth, and shocked audiences at his first solo show in New York. Guston truly did, as the title of this new book suggests, dedicate his life to painting—often at the expense of his personal life. This new book is a stunning survey by Robert Storr, who has spent three decades researching Guston and brings his own unique insight to this fascinating artist, including his obsession with the Italian Renaissance—and exactly which shade of red was his favourite. (Charlotte Jansen)

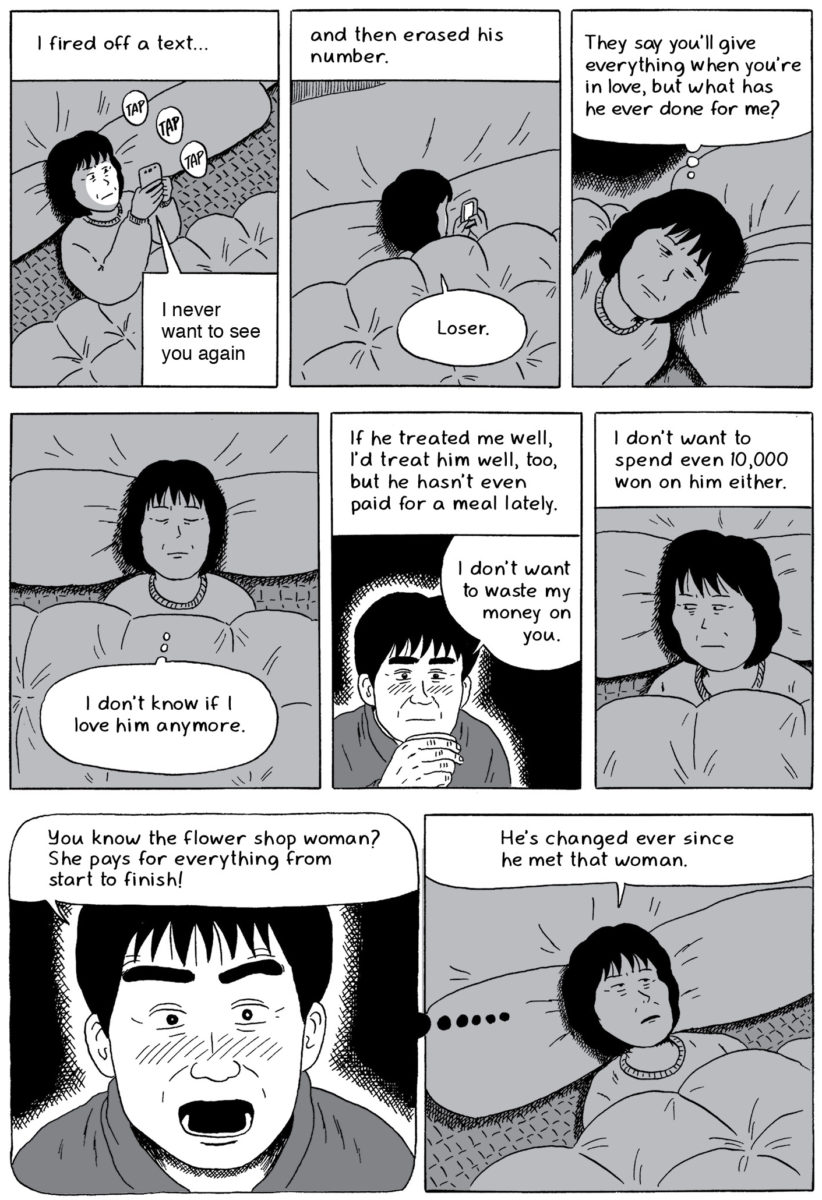

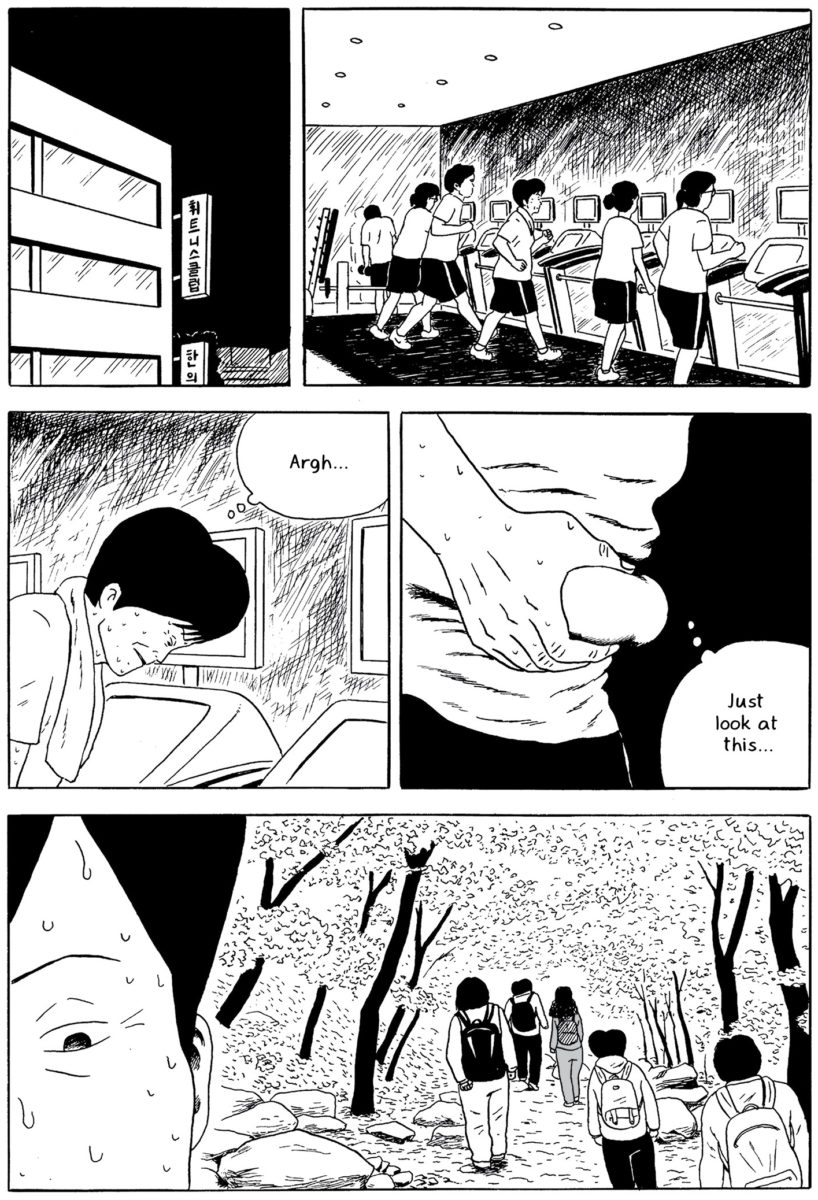

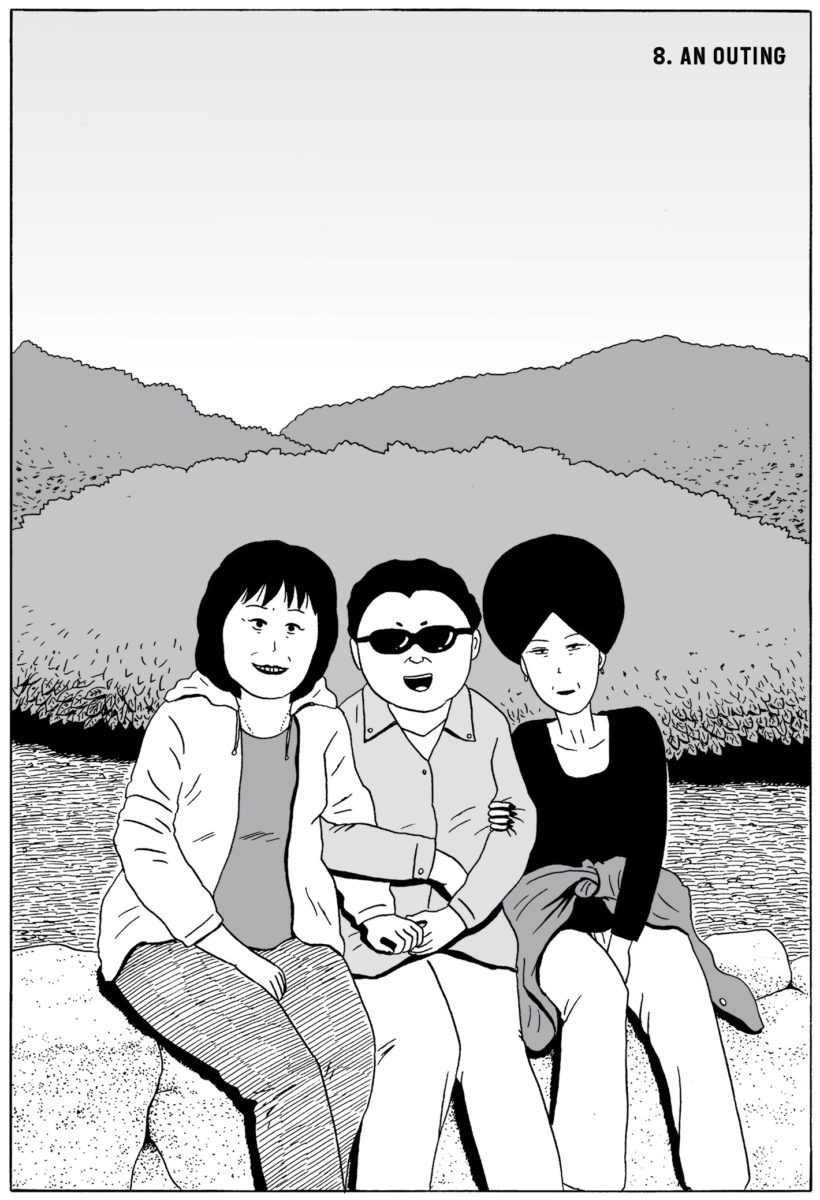

Moms, Yeong-shin Ma (Drawn & Quarterly)

In South Korean cartoonist Yeong-shin Ma’s debut graphic novel in English, Moms, he delineates a frequently ignored story: that of a seemingly unremarkable middle-aged woman. In this case, the protagonist is his own mother, and Ma’s process is fascinating. “I presented my mom with a pen and notebook, with a note on the first page: ‘If you want your son to find success, write honestly about you and your friends, about your love life and theirs,’” writes Ma. He went on to create the book of her stories from the notebook, which she filled out in under a month with details about her frequently disappointing boyfriends and their various addiction issues, work humiliations and gossip about her friends’ sex lives. As such, the book gently challenges stereotype, prevalent in South Korea and beyond, that it’s shameful for women in their 50s to lust and seek sex; as well as highlighting endemic loneliness in middle age. (Emily Gosling)

The Art of the Occult (White Lion Publishing)

Described as “a visual sourcebook for the modern mystic” this richly illustrated book celebrates the pervasive presence of magic across various fields of art and design. From the enduring power of sacred geometry; to the elemental force of fire, earth, wind and water; it takes an expansive look at how the occult has inspired artists, whether it be mythological subjects including witches, gods and spirits to compositional elements of shape and colour. Alongside well-known works by Leonardo da Vinci, Francisco de Goya and William Blake, more contemporary examples come from Pilar Zeta, Juliana Huxtable and Shannon Taggart. (Holly Black)

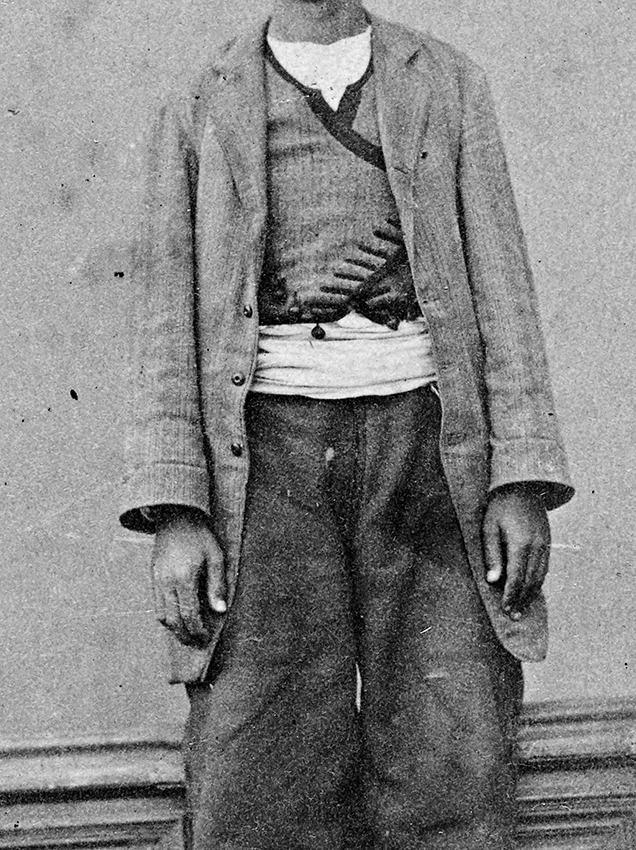

Hayal & Hakikat, A Handbook of Forgiveness & A Handbook of Punishment, Cemre Yeşil Gönenli (GOST)

The two booklets that make up this publication by photographer and artist Cemre Yeşil Gönenli reveal the ways in which photography has been used as a form of violence. Under the reign of the 34th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Abdul Hamid II, photographs of prisoners’ hands were used to decide their fate, after the Sultan read in a novel that “any criminal with a thumb joint longer than the index finger joint is inclined to murder.” Recognising the power of photography as a tool for wielding control, Abdul Hamid II had a photography studio set up in the Yıldız Palace in Istanbul to produce albums that were sent across the world. Conversely, he also commissioned photographs to be taken across the Ottoman Empire (though he rarely left Istanbul) in order to understand every inch of his own nation through visual imagery. This dual publication becomes a fascinating exploration of photography and a way to understand its meaning and function in the world. (Charlotte Jansen)