Poulomi Basu

Artist and activist Poulomi Basu has forced the law to change: her transmedia project Blood Speaks started in 2016 and focuses on the ritual exile of women who are menstruating or experiencing postpartum bleeding. This work resulted in a shift in legislation in Nepal. Women, their blood, bodies, and the various ways they resist, have always been the centre of Basu’s work. She focuses particularly on the resilience of women who have faced some form of violence, whether at the hands of those at home or from a society that is strictly patriarchal.

Basu works in whatever medium best suits the message (VR film, photographs mounted on lightboxes, books) using an emotive visual language whose poetry doesn’t undermine the reality of what her collaborators confront in their daily existence.

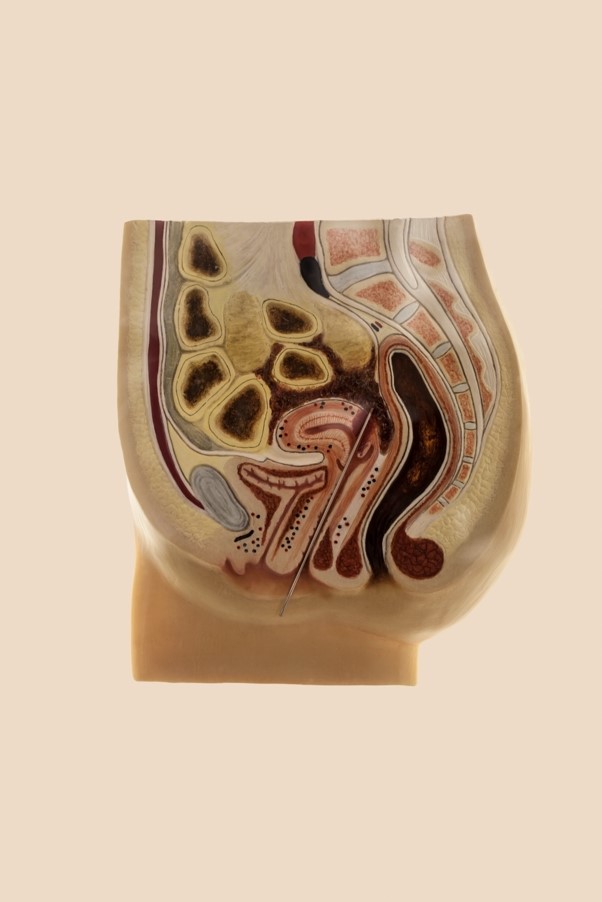

Laia Abril

Abril’s influential, award-winning work is based on extensive, deep research into subjects the world doesn’t want to see, or speak about, which disproportionately affect women. Her work constitutes an empathetic encyclopedia of the violence and oppression women experience in modern societies. Abril brings together texts and images on abortion, rape and eating disorders, and presents them as videos, books and installations. Her work isn’t for the pusillanimous, but visualising and visibility in Abril’s detailed, multilayered storytelling is urgent and leaves an enduring impression. She focuses on very real dangers, that, like women’s rights more broadly, continue to be drastically ignored.

Grace Ndiritu

All too often critique comes without consequence, or without any specific, practical way of implementing changes that can make a difference. Grace Ndiritu is one of few artists working today—and for the last three decades—who is pushing progress in real terms using art and spiritual rituals to inspire non-rational ways of thinking.

She’s led shamanic workshops that have led to policy changes around the status of climate change refugees in the EU parliament; established a community in order to understand how power structures proliferate; written groundbreaking essays—such as this one on the healing of America—and made films that explore the ways women can truly be set free. But it hasn’t been easy: Ndiritu’s practice is so radical that she has been sidelined and excluded from the art establishment for a long time. What she is creating is bigger than that though. It’s about interrogating the way we evaluate and engage with art; it’s a sustained challenge to all of the structures and conceits of the western patriarchy.

Gabrielle Goliath

In 2019 Gabrielle Goliath’s This Song Is For… explored the power of the dedication song, and reclamation through music. In the work, presented as a two-channel, immersive installation, we hear cover versions, all newly produced, chosen by survivors of rape. At a certain point, the sound is disrupted, like a broken record, which reminds the viewer that healing isn’t straightforward or linear for survivors who are often brought back to a place of traumatic recall. It’s not only the subject of the work that is so meaningful, it’s also the way Goliath made it—slowly, over many years, in collaboration with a group of women and genderqueer musicians.

In previous works, Goliath has explored issues around grief, sexualised and racialised violence by collaborating with female-identifying and queer performers and musicians using radical artistic methods that demand physical endurance and psychic effort. The result is a practice that puts the viewer in survivors’ shoes, without the comfort of closure.

Adelaide Damoah

“All of my performances have at their core the principle of Sankofa: the ancient Akan (Ghanaian) idea which tells us to learn from our past in order to live a better present and future,” Damoah says of her work. She is concerned with decolonisation, matrilineage and the physical strength and endurance of women over centuries of pain. In Damoah’s deeply moving, intense performances, the artist’s body becomes a paintbrush and history her canvas.

Damoah uses both her family’s personal images and experiences, and historical, archival records from the British colonial era. In a performance last year in New York, Into the Mind of the Coloniser, she dressed in Ghanain funeral clothes and conjured the image and spirit of her great grandmother, Ama. Later in the 23-minute work, Damoah invited the audience to cut her clothes, until she was stripped to her underwear; her body covered in red paint and dye. She then printed her body onto large sheets of colonial texts, bringing the idea of her body’s legacy and agency to the fore. Damoah proposes new ways of looking at diasporic history and its impact, first and foremost through women and their bodies.