This month the remaining commuters and shoppers to North London may or may not pass by Face to Face, a new exhibition of social and portrait photography curated by Ekow Eshun, the broadcaster, writer and former director of ICA in London. Displayed in the 90-metre-long King’s Cross tunnel, the series has been created in partnership with the Fund for Global Human Rights, presenting work from regions where the fund operates: Southeast Asia, Latin America, Africa and South Asia.

The work of the chosen artists: Alejandro Cartagena, Margaret Courtney-Clarke, Medina Dugger, Mahtab Hussain, Dhruv Malhotra, Sabelo Mlangeni, George Osodi and Kyle Weeks is wide-ranging, dramatic and heavily stylised. As is the case with all public art, its impact is far from pre-determined. Reception and meaning are constantly evolving processes, dependent on conditions far beyond the artists’ or Eshun’s control.

“Face to Face is a snapshot of a specific moment in multiple concurrent social histories“

The photos mostly present a single subject in each shot, some of whom are unmistakably associated with and defined by their surroundings—one example being George Osodi’s series Oil Rich Niger Delta, which documents the effects of oil mining of the lives of local residents over a four-year period. In Ongi Boy, the background shrubbery gradually darkens as it approaches the foreground, with inky black smoke framing the boy as if dissuaded from obscuring his figure; the reality of air pollution and environmental devastation is a different story. His clothing appears crisp and clean despite the visible fires burning behind him, his pose somewhere between a squint skywards and a dramatic, playfully self-conscious stance.

With the series, Eshun wanted “to highlight social documentary photography that functions as a form of engagement, dispensing with the ostensible objectivity of reportage photography and focusing instead on the subjective validity of lived experience.” One such example is Kyle Weeks’ series of self portraits taken by youths of the Himba population in northern Namibia. Weeks, himself Namibian, encourages the viewer to appreciate indigenous populations as diverse communities, rather than deferring to a single, internationally exported preconception which tends to reinforce stereotypes of otherness.

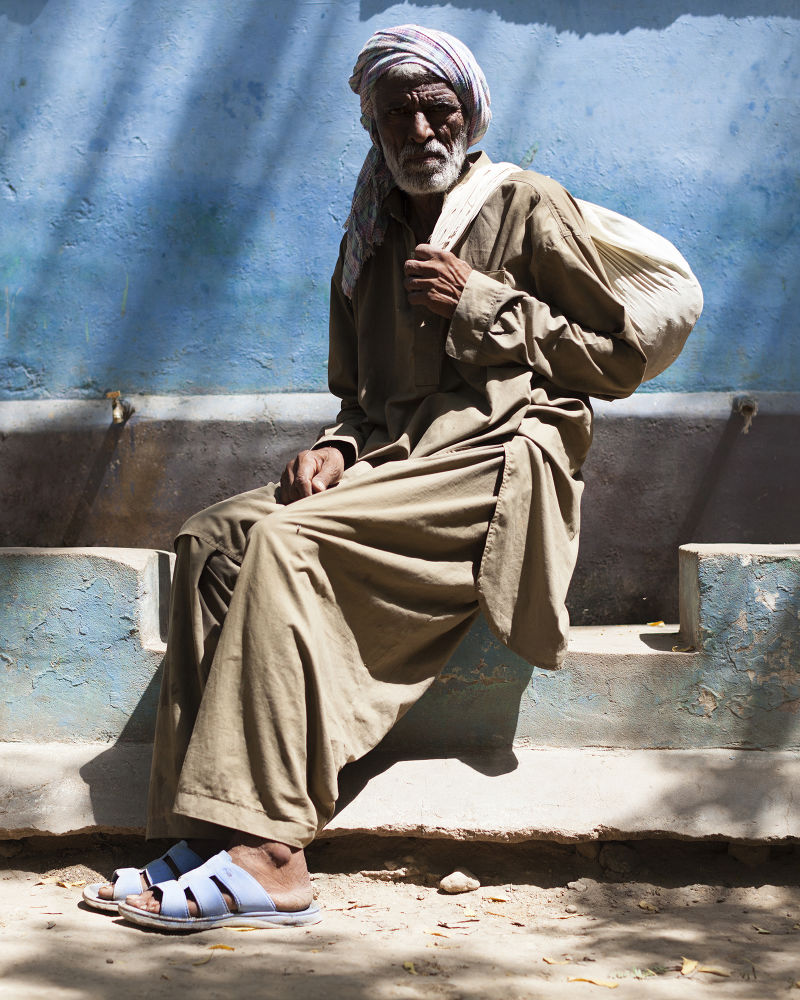

Weeks’ work illustrates the power of insisting upon proximity between the artist and their subjects, as well as allowing posers to participate in the capturing process. This creative collaboration raises questions about photographic agency and attribution, but Weeks’ subjects—all named and their location given—are depicted with ample sensitivity, though other works in the series, such Mahtab Hussain’s Man in Cemetery, do not carry the subjects’ names. Hussain’s image is no less powerful, though the decision to anonymise his subject represents a divergence in how photographers convey context and meaning to their audiences.

“Allowing posers to participate in the capturing process raises questions about photographic agency and attribution“

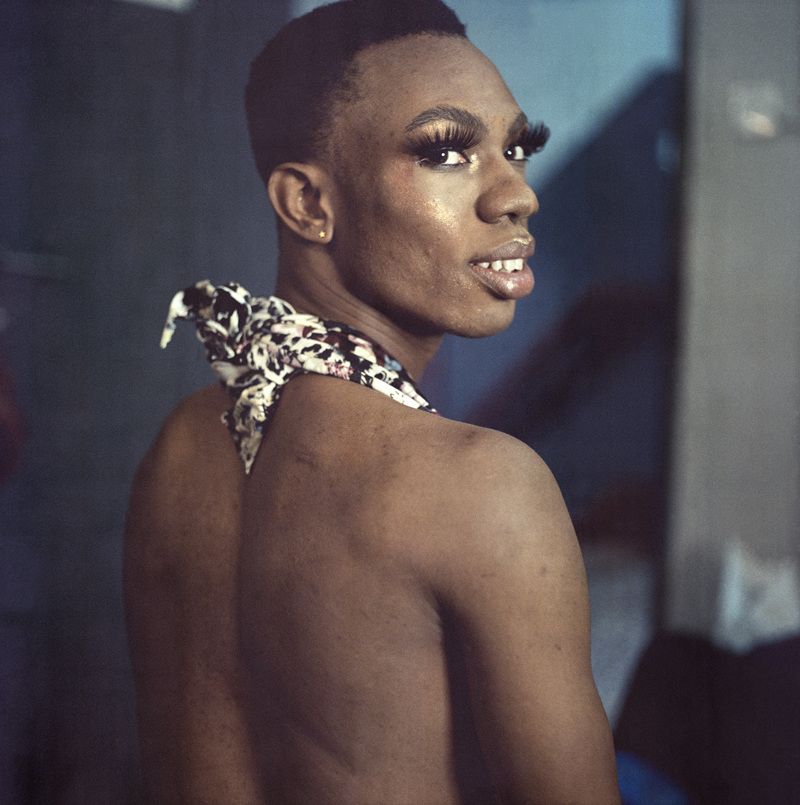

South African photographer Sabelo Mlangeni’s series The Royal House of Allure reveals a covert community, documenting a queer safe house in Lagos whose inhabitants are at significant risk given the country’s legal and social hostility towards LGBTQ community. Mlangeni describes how when he first met James Brown, the House of Allure resident asked: “If my country kicked me out because I collaborated with you, would your country give me a safe place to hide?”

The images are the product of these ethical concerns, each one representing a creative relationship of mutual understanding and trust, even if true sanctuary is still a distant prospect. In this sense, Face to Face is a snapshot of a specific moment in multiple concurrent social histories—and viewing them together does much to enhance our understanding of global diversity.