Format photography festival returns for its tenth iteration in Derby, UK this month, featuring more than 90 projects from artists and collectives around the world. After receiving over 800 submissions in response to an open call with the theme of ‘Control’, curators Louise Fedotov-Clements, Niamh Treacy, Laura O’Leary and Peter Bonnell have assembled a programme exploring the loose theme in a variety of styles, including works by Elena Helfrecht, Tami Aftab, Federico Estol and Sima Choubdarzadeh.

The works here explore control’s absence and presence in a range of global societies, as well as the structural conditions which produce and sustain it. Humans are controlled by illness—both physical and mental—but also state instruments such as the police and armed forces, while the rise of advanced surveillance technologies render some forms of control both invisible and practically limitless in scope.

One way to wrest back agency from oppressive forces is to co-opt its own tactics in liberatory ways. In Reduccion, Felipe Romero Beltrán’s restages the restraint methods used by police against undocmented immigrants in his native Spain with immigrant subjects, nullifying the acts’ inherent power imbalances and instead focusing on touch, the male form and choreography in a physical theatre-like display. The men were instructed by a national police officer for the shoot, lending an authenticity that (unlike the ‘Warning Zones’ in which Spanish police patrol) never veers into direct coercion.

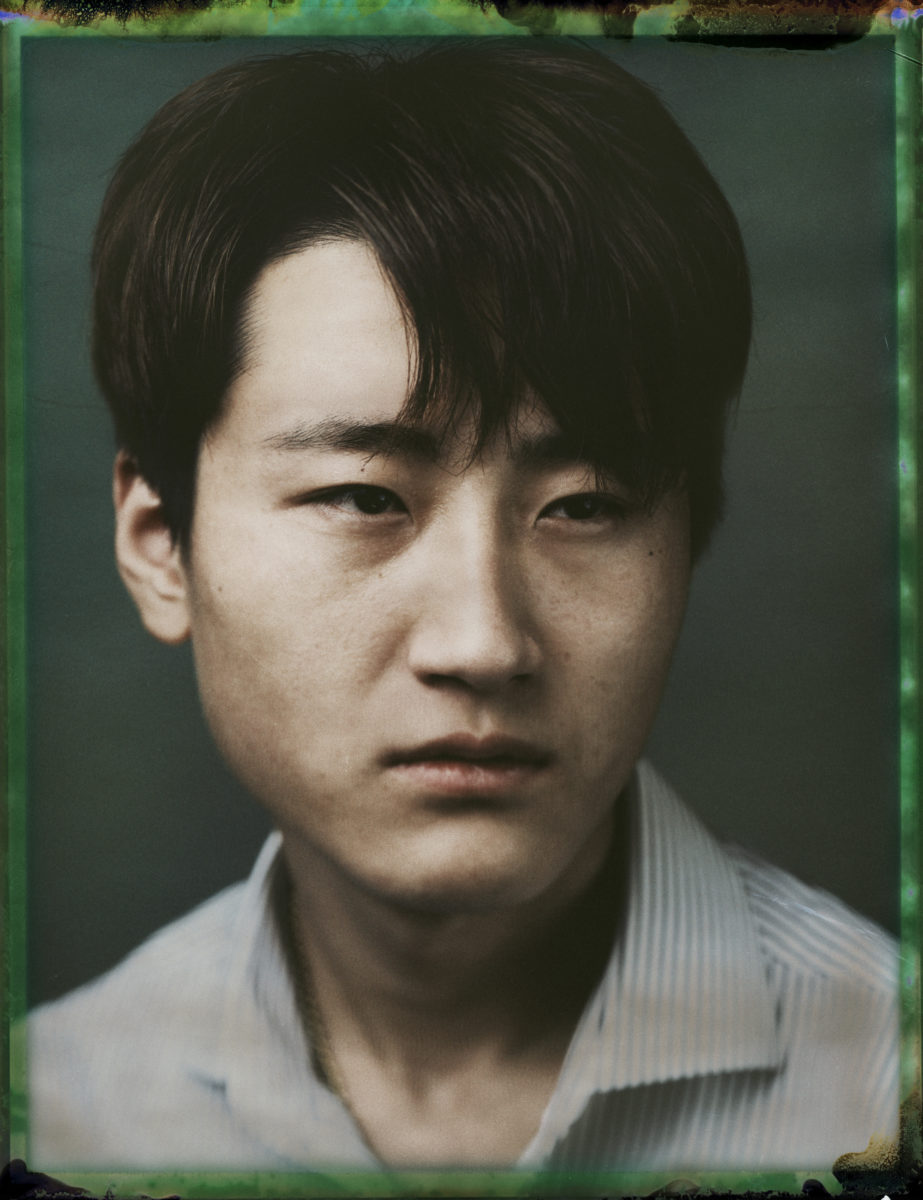

Etinosa Yvonne’s multimedia project It’s All in My Head addresses the violence-induced mental health struggles of the Nigerian population. Using manipulated portraiture, collage and animation alongside first-person testimony, Yvonne’s work makes visible the scars left by nearly two decades of terrorist attacks by Boko Haram and other groups. “I have had to run from Boko Haram insurgents on two different occasions and always run alone leaving my family behind,” reads a statement from a commercial farmer in Borno State. The images themselves feel introspective but resolute, often featuring a translucent effect laid over animation or images relating to the subject.

Etinosa Yvonne, It’s All in My Head, 2019-ongoing. Courtesy the artist and Format

Mental health is also explored from a personal perspective via Mitchell Moreno’s self-portrait in Pandemaniac. Alone in their London flat during successive lockdowns, Moreno creates expressive, installation-like shots exploring how the mundanity of the everyday can be inverted and stylised. Blood red walls and fabrics evoke a sensuality which belies the isolation of the past year, while thick make-up and costuming illustrate the performativity so central to Moreno’s practice. The theme of control is stretched and subverted across these mental health-related projects: it is at once something to be resisted, but, as in Reduccion, can be redirected in acts of positive appropriation by the artists and their subjects.

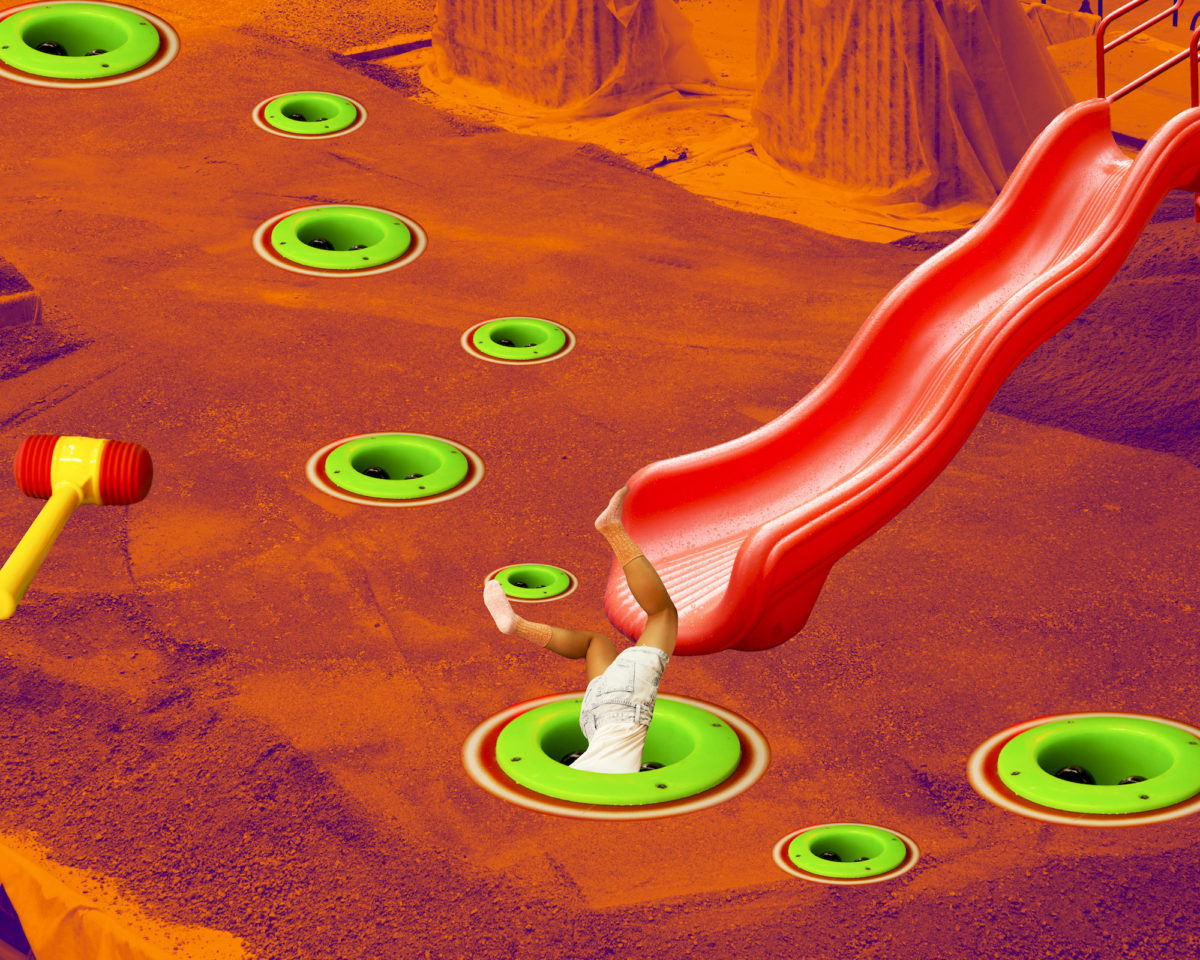

Dávid Biró’s Do You Accept Cookies? perhaps best illustrates the widening of the theme of control to capture a cross-cultural moment. Instead of focusing on the individual experience, he questions the ways that societies impose structures of recognition onto their citizens, which, via mass image collection, flatten the individual into a series of data points. Biró’s face-imitating installations question what the viewer recognises as human, inverting the role of surveillance cameras to highlight the potential dangers of such technologies.

He also uses various hacks to detect the blind spots and biases of facial recognition technology. Control here becomes a currency to be fought over by governments, activists and citizens with profound social and political implications. Despite the agency that these artists explore throughout their work, widening our understanding of control often involves ceding it to unknown forces.