In December 1988, Neneh Cherry performed her hit song Buffalo Stance live on Top of the Pops. The song is still a banger. Cherry performed with the energy and charisma of the 24-year-old star she was then. Only more recently have I come to realise that in that performance Cherry was 8 months pregnant, her neat bump visible under a tight-fitting miniskirt. For my generation this was a definitive moment, though I was too young to realise what it meant at the time. Of course, Cherry’s decision to perform at that stage of her pregnancy was questioned and criticised at the time. I thought of it again only in 2009, watching MIA perform Paper Planes live at the Grammy Awards, on her due date. Next it was Beyonce’s turn at the Grammys in 2017; dressed, like Cherry was, symbolically in gold and pregnant with twins.

These epic moments of pop cultural history showed pregnancy, and common misconceptions about the limits and constraints of motherhood, in a completely different light within the mainstream. It was a firm two-finger salute to a culture that describes pregnancy as a ‘condition’. In the 2010s it also produced an unrealistic image of mothers, the archetypal madonna figure now beautified in the place of beatified, and unimaginable for most mothers.

I like to revisit Cherry’s defiant performance on YouTube, but I also return to photographs that deal with birth and its aftermath. These are a reminder of the physical labour of becoming a mother, where there is space for nuance and ambiguity. On mother’s day, many mothers will be reflecting on the time, or times, they became mothers, however that may have been and however long that may have lasted. It’s a day that is laced with grief, pain, loss, trauma—as much as eliciting joy and sweetness of nostalgia. Works of art bear witness to this in ways no staged performance can; they bring us in closer to contemplate the core of human existence.

“It’s a day that is laced with grief, pain, loss, trauma—as much as eliciting joy and sweetness of nostalgia”

Iringó Demeter depicts a pregnant woman slumped in a plastic chair; Demeter’s trademark up-close perspective means pregnancy is not the first thing we notice about the picture. The formal beauty of the lines, the shadow, the unusual posture of the pregnant woman—it is a subtle reminder of the warmth of body in close proximity, the warmth Demeter alludes to in her title and its inexpressible vitality. Motherhood is perhaps as simple as that: one body a nurturing cocoon for another.

Elinor Carucci. My Belly After Giving Birth and C Section, 2004. Courtesy the artist

Elinor Carucci has made many images about the maternal but one sticks with me: a self-portrait of her body in 2004, the taped wound from a c-section still visible, the linea alba too, running over a belly still swollen and a now vacant womb. It would be too straightforward to interpret this image as a rebellion against what we usually see of pregnancy and birth—to me it looks more like a battle cry, proud and triumphant. As mothers there is no limit to what we put ourselves through, physically, mentally, emotionally. This endless well of resilience is what is too often overlooked. C-sections are so routine that we forget what has happened in that procedure to a woman’s body; how deep that cut has to be to pull a child out.

“As mothers there is no limit to what we put ourselves through, physically, mentally, emotionally”

The experience of becoming and being a mother may connect with something universal in nature, but it is profoundly changed by politics and culture. Jon Henry’s series Stranger Fruit is a reminder of this, a series created for, with, and about mothers of Black men in the US. Based on the pieta, and inspired by subsequent interpretations of it by Renee Cox and David Driskell, Henry’s mothers carry their children in their arms, imploring and accusing. Henry collaborated with mothers who have not lost their sons—but they live with the threat and fear every day. The images were created as a response to the murders of Black men in the US now, but the grief hits like a tidal wave that isn’t confined to the specifics of time or place. Their worst fear is my fear, and I imagine, the worst fear of any parent.

Lisetta Carmi’s unforgettable document of a birth in a hospital in Genoa in 1965 was intended as an informative document, with a medical, full-frontal attention to the moment in which one body emerges from another. It doesn’t give agency to the mother—we don’t know who she was, we can’t see her face, and the viewer is exposed to a view she didn’t have—but it is an attempt to demystify the act of birth. The mother’s individuality is erased but she stands for something that reaches towards the universal in our existence.

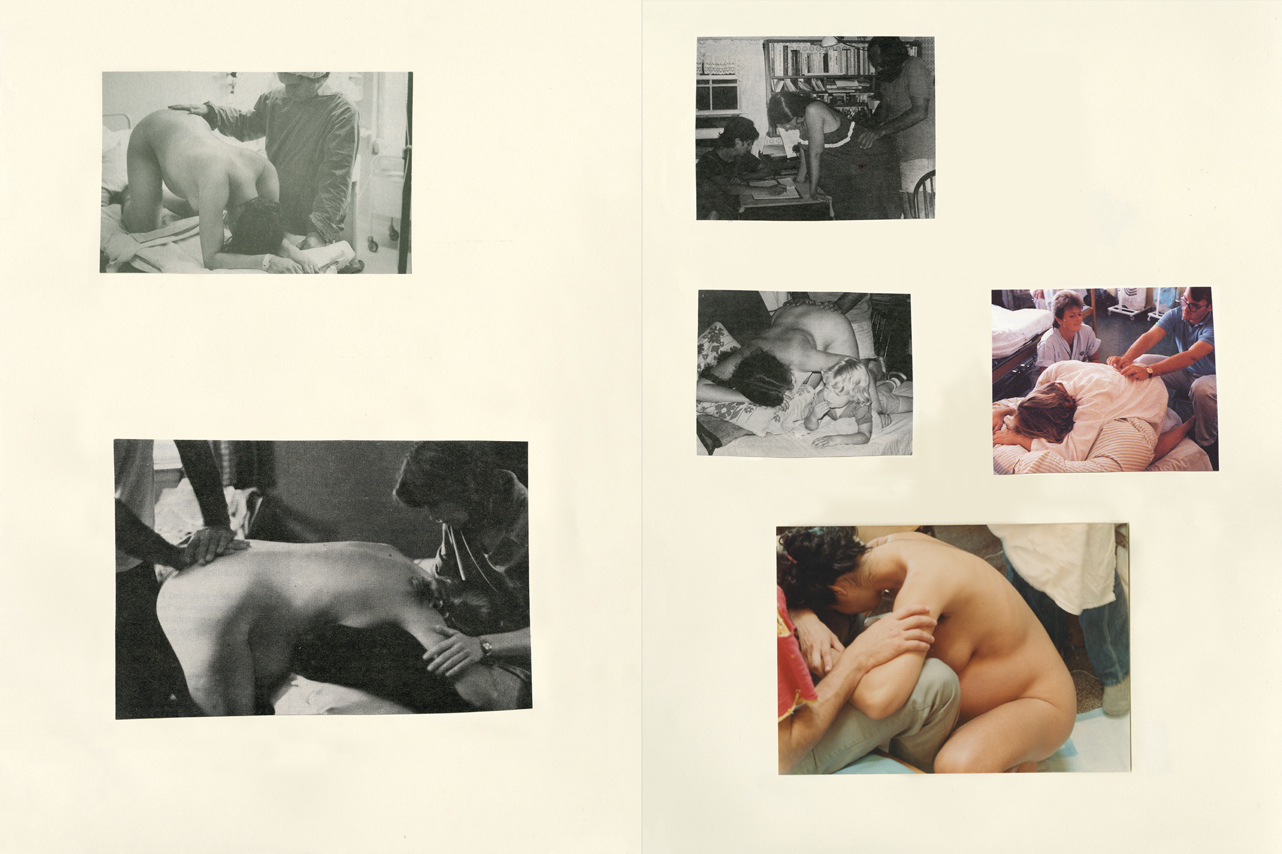

In My Birth, composed of over two thousand images of women preparing for and in the process of labour and childbirth, Carmen Winant brings together such documents of birth created in the 1960s and 1970s with similar motives to Carmi. Multiplied and seen together through Winant’s eyes, it has a staggering effect; the collective productivity and force of women. It’s hard to accept, travelling the images of her vast installation, how that power has been subdued; how mothers are rejected and ridiculed.

In 2020 Maggie Shannon offered a counter-narrative, in her series documenting women as they become mothers at birthing centres in Los Angeles during the pandemic. Here we see Shalom Montgomery and Tsune Brown, whose son was born at the New Life Midwifery Birth Center in Arcadia, California, with the help of midwife Chemin Perez. Their story, and the others who let Shannon photograph them, allowed the narrative to come back to mothers and their inherent strength: the physical demand, the drama and determination, the courage needed to give and sustain life.

“The experience of becoming a mother may connect with something universal in nature, but it is profoundly changed by politics and culture”

Most of the visual symbols associated with mother’s day represent passive femininity—cut flowers, which harks back to the origins of Mothering Sunday, celebrated on the 4th Sunday of Lent in the Christian tradition, called Mothering Sunday because families in Britain would visit the ‘mother’ church, the largest church in their area, with children plucking wild flowers to hand to their mothers on the way. Embedded in this is the idea of devotion and dedication, the recognition of the mother as all-encompassing energy; the physical creator of the divine; the protector of humankind.

Audre Lorde described her approach to motherhood as teaching her son the same way she taught her daughter; how “to move to that voice from within himself, rather than to those raucous, persuasive, or threatening voices from outside, pressuring him to be what the world wants him to be.” This what we owe our mothers: the autonomy to be.