New York- Beverly Semmes is a painter whose palette seemingly includes every material under the sun, from tulle, velvet, clay and crystal to vintage porn magazines, and, of course, paint. (She even once made floor mats from Band-Aids). The New York–based multidisciplinary artist has been pushing the boundaries between fine art and craft since the late 1980s.

Her visual language — an amalgamation of soft sculptures, gestural brush strokes, large scales, vivid colors, irregular vessels — communicates the tension between exposing and revealing the gendered body. A puritanical desire to conceal gives way to a pointedly feminist reckoning with the performance of identity and sexuality.

At last month’s Independent NY art fair, in a booth by Susan Inglett Gallery and Specific Object, Semmes’s paintings superimposed atop 90s-era porn magazines from her “Feminist Responsibility Project” hung alongside Yayoi Kusama’s nude photography series and Lynda Benglis’s handmade Artforum T-shirts. The booth titled “An Assault on American Prudery,” highlighted the ways Semmes and her peers have challenged the male gaze and reframed sexualized depictions of women over the years. Her mixed-media painting Glitter Brick Triptych, 2023, which featured a collage approach to the same source material, was on display at Kapp Kapp gallery’s booth.

Back at Semmes’s studio, the artist leans across a table to show me screenshots on her phone from her recent installation for a group show titled “Black & White” at Shoshana Wayne Gallery in Los Angeles. In the photos, two art installers carefully unfurl one of her seminal large-scale dress sculptures, Buried Treasure, 1994. The young men’s bodies appear in sync with the movement of the black crushed velvet dress; they bend and reach to release a charcoal ribbon of sleeve (approximately 30 feet long) in a careful criss-crossing motion.

“I never saw the installation process as a performance before this” she observes. As we watch the installers, she likens the process to Jackson Pollock’s dance-like movements, splattering paint across his studio floor. “It takes a certain kind of focus, you have to calm yourself,” she adds.

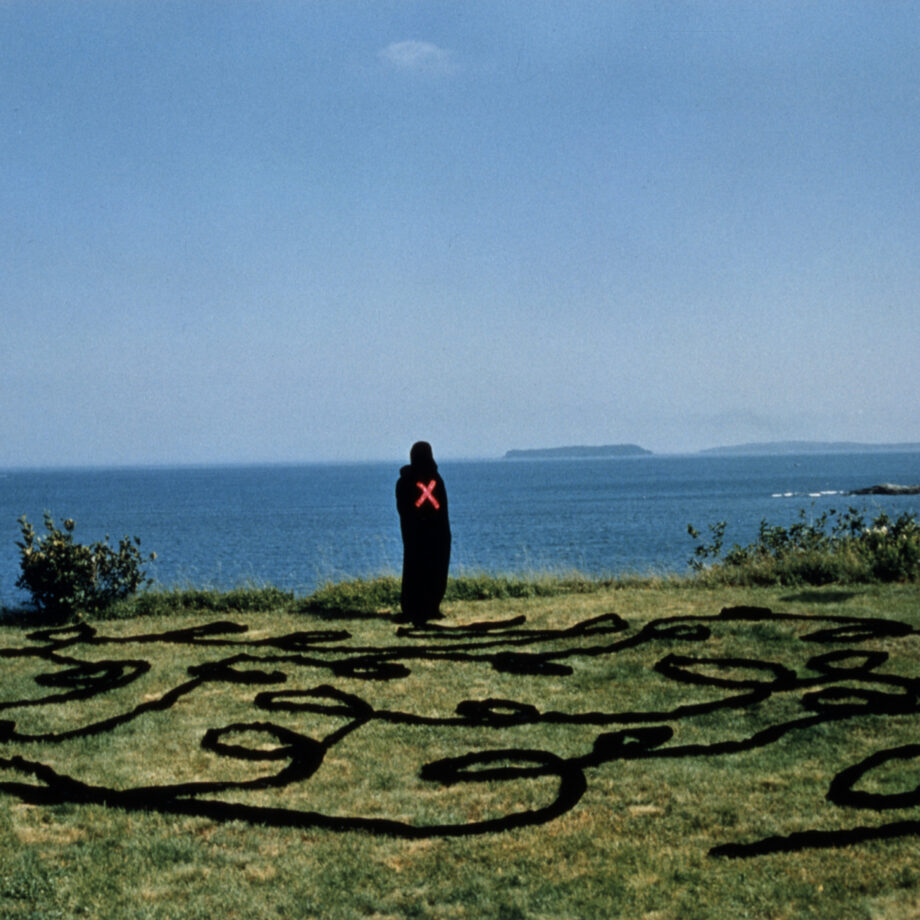

Semmes picks up a book of her work from the table and opens it to a photo of Buried Treasure from the year it was made, worn by a figure with their back to the frame, a red “X” emblazoned across the dress. A green cliff and a slightly lopsided horizon sets the stage. A glimmer of an American flag peaks out from the top right-hand corner of the frame. The dresses’ tendrils spill forward across the grass. Apart from the flag, there are no other markers of identity: the figure is anonymous, the dress unisex.

“I thought of my works as landscapes,” she says, the image bringing back memories from her early days. “Growing up in the 70s, I definitely identified as a feminist, but as an artist, I didn’t see my works as holding feminist messages.” Instead, she saw the dresses as trees. The draped fabric strewn across the floor: roots, a waterfall, a pool, a bush. And, as I look at the photo of the dress with the ocean in the background, I see it too. I note that there are lots of comparisons to be made between the ways men treat the land and the way men treat the female body.

The artist began to understand the feminist readings of her works after curator Marcia Tucker visited her studio leading up to a feminist group show, “Bad Girls,” at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in SoHo in 1994, featuring Semmes alongside artists like Nancy Dwyer, Cheryl Dunye, Xenobia Bailey, Renee Cox, and Margaret Curtis. “I thought that landscape was a big subject, and it hadn’t really occurred to me that feminism on its own was a big subject or that I would be biting off something to do for a long time,” she says.

Semmes’s ongoing “Feminist Responsibility Project” began in 2002, when a friend in upstate New York gave her a stack of 1990s-era X-rated magazines including Penthouse and Hustler. “I put them in a drawer for quite a while before I pulled them out and eventually drew on them.” The magazines gave the artist the opportunity to downsize, to imagine, for once, creating clothing for the Lilliputian sized women on glossy 8 x 10 pages rather than larger-than-life figures. In the early aughts, Semmes began to obsessively cover up the nude models, channeling her puritan grandmother (not to be confused with the grandmother who introduced her to sewing as a child) from her kitchen table. “In a way, it was a performance of her,” she reflects, “a prompt, a jumping off point.” And with that, Semmes jumped off into a series that she continues to work on to this day. A few years after its inception, she landed on a title that is both self-aggrandising and silly.

“Why the name?” I ask. “It was during the Bush years and we were hearing all this talk on the radio about responsibility and assigning personal responsibility to people in an effort to support this agenda that would have less public programs,” she reflects. “I thought this will be my responsibility: I’ll fix all the porn. It kind of cracked me up; it seemed so ridiculous.”

In the last two decades, Semmes has made hundreds of “FRP” works, often revisiting and reworking images. “With a few strokes, I can change them so much; I can undermine whatever the thinking was behind the original,” she says. The anonymity of the models is both amplified and challenged by her hand. Her colorful brush strokes and lace-like scribbles conceal, to a degree; they also set each woman apart, imbuing the characters with a sense of personality.

As fate would have it, Semmes now counts one of the models as a friend. The two officially met at a party about a decade ago, whereupon learning of the woman’s past successful adult modeling history, the artist asked her if she could identify herself in any of the paintings; she could. It turned out that the model had been featured in numerous of Semmes’s works. “She came down for the Susan Inglett show where I had a big image of her, and we took pictures in front of it,” she tells me. “I’m always showing her my work and asking her ‘is this you?’” She adds that the model didn’t express any hangups about her past: she viewed her job as glamorous, a professional performance that required physical stamina (the ability to hold contorted poses) and the understanding of how to play a role.

While the artist’s work has shape-shifted over the years from soft sculpture to ceramic to painting and collage, performance has been a through line. Before the artist made fabric sculptures to hang on walls, she was creating costumes for short Super 8 films while pursuing an MFA in sculpture at Yale University in the late 80s. “I had a comfort level with the costumes,” she said, noting that textile’s existence outside of the art world allowed her the space to experiment. She often styled her friends and family in the oversized garments, photographing them in nature or manicured gardens. Her dresses hung on the empty walls of her studio in-between performances. “I realized that I liked how they looked on the walls as much as the photographs that I was taking of the performances,” she muses.

Semmes’s dresses grew and grew until they outgrew the parameters of what is considered clothing. They began to take the form of monumental soft sculptures; the performances moved from outdoors to gallery rooms. In Watching Her Feat, 2000 — a fluorescent canary-yellow installation that engulfed the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia with piles of tubular fabric — gallery attendants took shifts sitting on a chair facing the massive work, dressed in matching yellow jumpsuits; red light set the room afire, filtered through curtains. In Petunia, 2001, a model-cum-attendant sat in a deconsecrated church, clothed in billows of pink chiffon. A sprawling pool of the same fabric covered the floor of the room. Once an hour, the woman rose and glided around. The light-filled space was tinged pink by the reflection of the fabric.

In a more recent work, Marigold, 2022, a royal purple velvet gown cascades down a wall into a pool of organza that holds various symbolism-packed objects including a plastic black lab that now lives at Semmes’s studio. A yellow McQueen dress peeks out from beneath the gown’s skirt. Semmes was commissioned by Alexander McQueen creative director Sarah Burton along with eleven other women artists to create works based off of looks in the luxury brand’s latest collection.

At Semmes’s Brooklyn Navy Yard studio, the leftover yellow scraps from the aforementioned McQueen collection poke out from neat bags of fabric, overflowing onto a table: “This is my inventory,” she says, pulling out seemingly endless bolts of textiles. Semmes runs a sheer blue-gray scarf between her fingers, thumbing its velvet polka-dots. Each piece has a story: fuschia pink, translucent blue, material that looks like tree bark, red velvet, a fuzzy scarlet swatch with diamond slits. The artist has built up her collection over the years from her early downtown studio, trips to Japan, fabric stores on Orchard Street, materials given to her and found on the street.

A closer look at a varied practice reveals a shared DNA that examines what it means to take up space in the world. By the studio’s front door, a sculpture of clay pots stacked atop each other from her “Sketchpot” series of anti-ceramics sets the tone. Across the room, a ceramic cup nestled on a pedestal surrounded by fake fur recalls Meret Oppenheim’s fur lined teacup. Nearby, an unfinished canvas is sprawled out on a table; small metal pins jut out from the edges of velvet circles — Semmes contemplates ways she can incorporate the pins into the mixed-media work.

A rug with Pink Pot, 2008, printed on it hangs, folded in half by the back wall; a bare midriff, crouched nude legs, and open toed black heels poke out from the loopy handles of a fuschia vessel. Images of her works appear printed across various customized merchandise: trucker hats, aprons, rugs, and pillowcases, scattered like easter eggs throughout the space. There are also objects printed with photos of garments by CarWash Collective, a collaboration between the artist and Jennifer Minniti, a designer and a professor and chairperson of Pratt’s fashion department. So far they have staged gallery presentations and performances. Next year, the two plan on presenting a new CarWash project at Kapp Kapp.

Semmes pulls a white pillowcase out of the piles of fabric: a photo of a model wearing a CarWash collective dress is printed across the front. I note that her work seems to flirt with fashion while remaining in the art world. She has taught figure drawing in the fashion department at Pratt Institute, and she plans on teaching at the university’s new fashion MFA program next year. Maybe the divide between the two mediums is just a line in the sand, or a spectrum, I offer. She nods in agreement: fabric has been appearing more and more in her paintings, and she and Minniti have been discussing creating a “full-on fashion show.” She is also preparing for a large-scale installation project with Tufts University Art Galleries featuring fabric dyes manufactured by the university’s silk lab, and a solo exhibition at Susan Inglett Gallery — both next year.

“There’s a whole dress that’s under here,” she says as we inspect a current work-in-progress hanging on a studio wall: an image of a model with an unplaceable smile stares out from behind a light-blue and red painted vessel topped with patchwork squares of rich, brown velvet. She takes the painting down to reveal a black velvet dress draped over the back. The possibilities of clothing shine through Semmes’s work, even hidden away, tucked on the back of a canvas.

Words by Meka Boyle