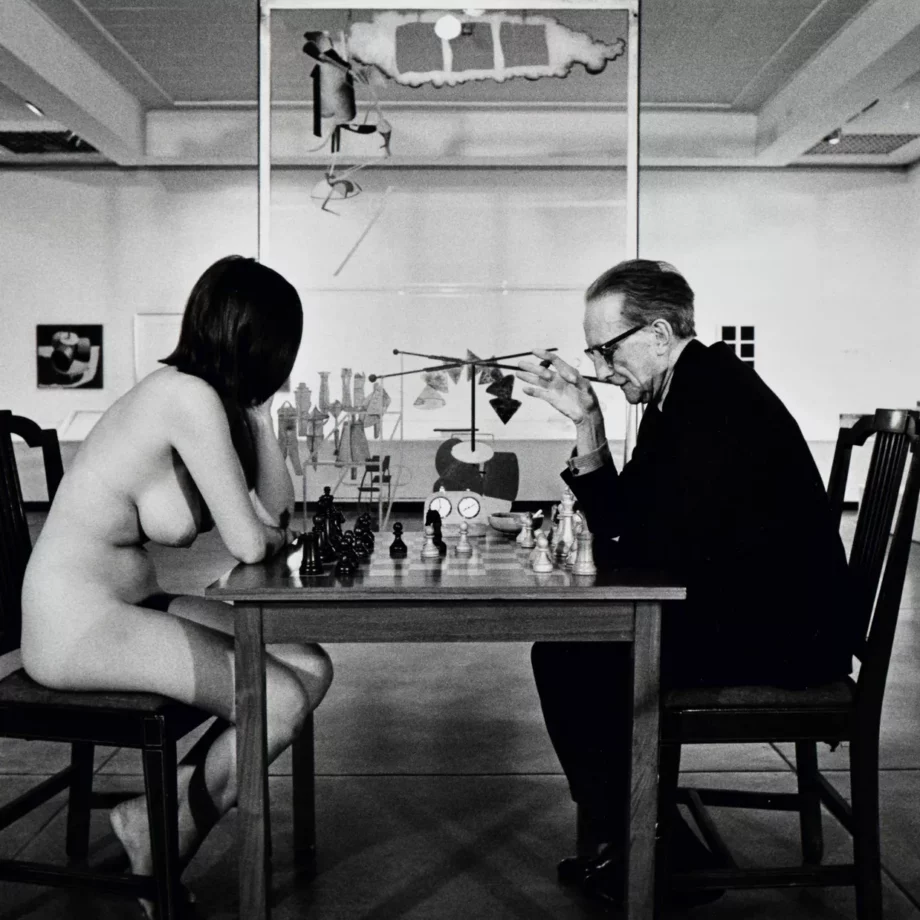

When Eve Babitz undressed to play chess with one of history’s greatest living artists, it was in a manner as effortless as her writing, her self-described “breezy landscapes” of hedonistic nights at the Chateau Marmont or the Polo Lounge. Julian Wasser’s 1963 photograph (Julian Wasser, Duchamp Playing Chess with a Nude (Eve Babitz)) and Babitz’s writing and tour de force personality permitted me to embrace both my bottomless appetite for pleasure and the urge to spill it all on the page.

“This large, too-L.A surfer girl with this extremely tiny old man in a French suit, playing chess” is how Eve Babitz described the infamous image of her playing chess, nude, against a clothed Marcel Duchamp, an odd-couple Adam and Eve for the sexual revolution.

If someone embodied the hedonistic potpourri that was Hollywood in the 60s and 70s, it was Eve Babitz. And in classic Eve fashion, she stripped nude in the chilly draft of the Pasadena Art Museum to make her married boyfriend, curator Walter Hopper, jealous.

Eve (it feels only appropriate to be on a first-name basis with her) was the original LA Woman, daughter of a well-respected studio musician, and goddaughter of Stravinsky, she, like Wasser, was a chronicler of the City of Angels. “LA has no sense of history”, she once wrote, “that’s why I’m always writing down my memories”.

The good-time girl with a notepad, her speedy musings appeared in major magazines like Vogue, Rolling Stone and Cosmopolitan, but she also wrote a dizzying and delicious blend of memoir-fiction (Eve’s Hollywood; Sex and Rage; Slow Days, Fast Company; Black Swans; I Used to be Charming), and even moonlighted as a photographer and record cover artist for hip peers like The Byrds and Linda Ronstadt.

Eve was more than a muse. She was a confessed adventuress. She even gifted us with the backstage-pass essay, “I Was a Naked Pawn for Art”- wisecracking that she didn’t like Wasser’s photo because her birth control pills made her breasts look like “two pink footballs”, that getting nude meant “pretending I was way bolder than I really was”.

These types of fizzy one-liners permeate her writing, revealing a commitment to a way of expression that is just as much self-mystique as it is real life, in all of its glory- champagne and caviar, quaaludes and swimming pools, but also bodily fluids, weight gain, sexual rejections, drunken mishaps.

In today’s climate, where social media filters like Facetune are overused, and Botox is as routine as going to the dentist, Eve’s authenticity- not liking her body and still capturing it on film, forever- feels revolutionary.

And when I look at Wasser’s photograph, it isn’t her body that I am drawn towards. It’s her voice, still louder than her nudity. In her writing, Eve’s voice always strikes, iron hot, self-possessed, not a kitten under male hands but a tiger out prowling on the sunset strip, seducing the likes of Jim Morrison and Harrison Ford, spilling champagne down her dress and writing it all up afterwards, with no details spared.

Art history has usually placed the nude female form as an object to be admired by a typically male gaze, where women’s naked bodies are stripped of their autonomy. Yes here is Eve, not playing a part except that of herself. Wasser’s photograph is the coming together of two symbols of their age- Duchamp, of the Old World of art, the masculine merry prankster, and Babitz, the thoroughly modern young woman with a mouth that’s good for more than blowjobs. Although she was good at those too, she once quipped, that’s why her ex-lovers always stayed in touch.

In the photograph, there is nothing illicit or exploitative about her nudity. Here is my body: checkmate.

While men may be busy getting distracted by Eve’s ample chest (something she even wrote an entire essay about), she is busy winning them over, always one move ahead. Using her charm to garner access, all of which turned into material for her writing. And in documenting her restless exploits, she turned the whole idea of a nameless, faceless nude muse on its head. This is the woman who wrote an entire love letter to men and their perfect legs (“cowboy, athletic and my beloved scrawny rock n roll”), the unabashed appetite of a woman who once described a man who “looked so much like a leopard skin that all you wanted to do was lie on top of him naked”, who objectified men in a manner that is hilarious and for me at least, relatable.

Before my own visit to LA recently, I had never seen an orange tree up close or the jacaranda and bougainvillaea that litter Babitz’s orbit, but I was familiar, reading her, with the taste of sleaze, chasing neon lights, crazy for a scotch and soda and a man twice my age, but mostly, of wanting to be seen and heard. I thought the point of living was to collect adventures and have the wildest stories. I had used my body but never fully embraced it, except when I lived in Sweden and got into swimming. My body was a thing I ignored for the cerebral x and o’s of my brain and my fingertips on a keyboard to write all of those crazy stories down.

Babitz’s writing is hot-blooded, all-body. Her words are as texturised and visceral as sunburnt oil-slicked skin diving into a pool, whether writing about Jim Morrison and his “edible smile”, kissing men who look like trouble with “shoulders like angel wings and eyes like turquoise pools”, or writing about lavender flowers that look like “cotton candy clouds”, sunsets as “grandiose carnivals in the sky”.

And throughout her work, sex and its intrigues play out across the glamorous restaurants of LA, where her bottomless appetite for pleasure also extends, refreshingly, to food. Eve’s idea of romance is sitting in a towel with a wealthy and handsome older lover gobbling shrimp after

skinny dipping or the joy of finding real pie and real hamburgers on an impulsive road trip with a pen pal lover. She even once wrote an ode to the all-night supermarket food aisles at Ralph’s. Drinking bloody Marys at Musso and Frank’s can “cure anything”. She loves “capers more than life itself”. A cure for a nervous breakdown or rage is a “hot fudge sundae”. After making love with a beautiful man after swimming naked in his pool, her first thought Is: “I’m hungry”. Which is to say, she’s best read at a bar drinking a cocktail the colour of a desert sunset and enjoying a guilt-free dessert.

In 1970s literary LA, there was also Joan Didion, whom Eve was often pitted against. I remember looking at photos of Joan and almost feeling a sense of despair. I could never be that person, that type of writer. But I could also never be that small. Her cool-customer aloofness seemed embedded within how petite she was, all sharp edges, how she could slip through scenes unnoticed. Eve feels like the antidote to this. “I never display any of those womanly qualities so praised through the ages like modesty, tact or sweet vulnerability”, she writes in Slow Days, Fast Company.

Growing up, what I learnt about my body was shame. Wishing I wasn’t so tall, was more flat-chested, and could hide away. Eve’s casual attitude toward stripping off in Wasser’s photograph also extends to her imperfections, and all with a playful deprecation, “I became interested in playing and tried to stop thinking about holding in my stomach”. But it shows a person who isn’t willing to hide.

Reading Eve still feels like a most reliable and thrilling relief, like exhaling out a sucked-in stomach and then sipping on a dry martini. Taking a bite from a delicious pastry and wolfing down a glass of champagne. Eve is not only a good time, but she makes me feel like having a good time is the most important order of the day, and that means not only being in one’s body but being unashamed of it—no Didion-esque slinking in the shadows under enormous sunglasses like an expensive Siamese cat.

A lack of a flat stomach was not an obstacle to charming the pants off of everyone or having fun, or making history by being a new, more modern kind of nude, and besides, as Babitz once wrote,

“I just wasn’t perfect. And I have never liked perfect things. They give me the creeps”.

Words by Katie Driscoll