Three years ago, I was visiting Manchester, talking to a Salford based musician and self-proclaimed Northern mystic named Black Lodge. Under an informal agreement made half an hour prior in a local spit and sawdust pub, he agreed to be interviewed for a radio documentary on The Fall’s Mark E. Smith in exchange for red wine. He had with him a skull that he carried around in a Piccadilly Records tote bag, which accompanied his improvised performances at his beloved King’s Arms in Salford. During the evening, diverted by many conversational off-roads, it became evident that Black Lodge’s fascinating history eclipsed his fabled encounters around the Northern Quarter with Mark.

Born under the birth-name Daniel Dwayre, Black Lodge spoke about growing up in Newhey in the early 1980s, a northern industrial village close to Rochdale. He told me about the profound influence of William Burroughs’s cut-up method on his creative practice and life, his time spent with Joseph Beuys’s Free International University in East Germany as a young man in the late eighties, living in anarchist squats, the implosion of punk in Britain, Factory Records, the occult works of Austin Osman Spare and Aleister Crowley, serendipity, the media and necessary magickal counterbalances, selling his record collection to purchase a meditation gong, and his recent experiences under the influence of DMT, the powerful hallucinogenic tryptamine drug.

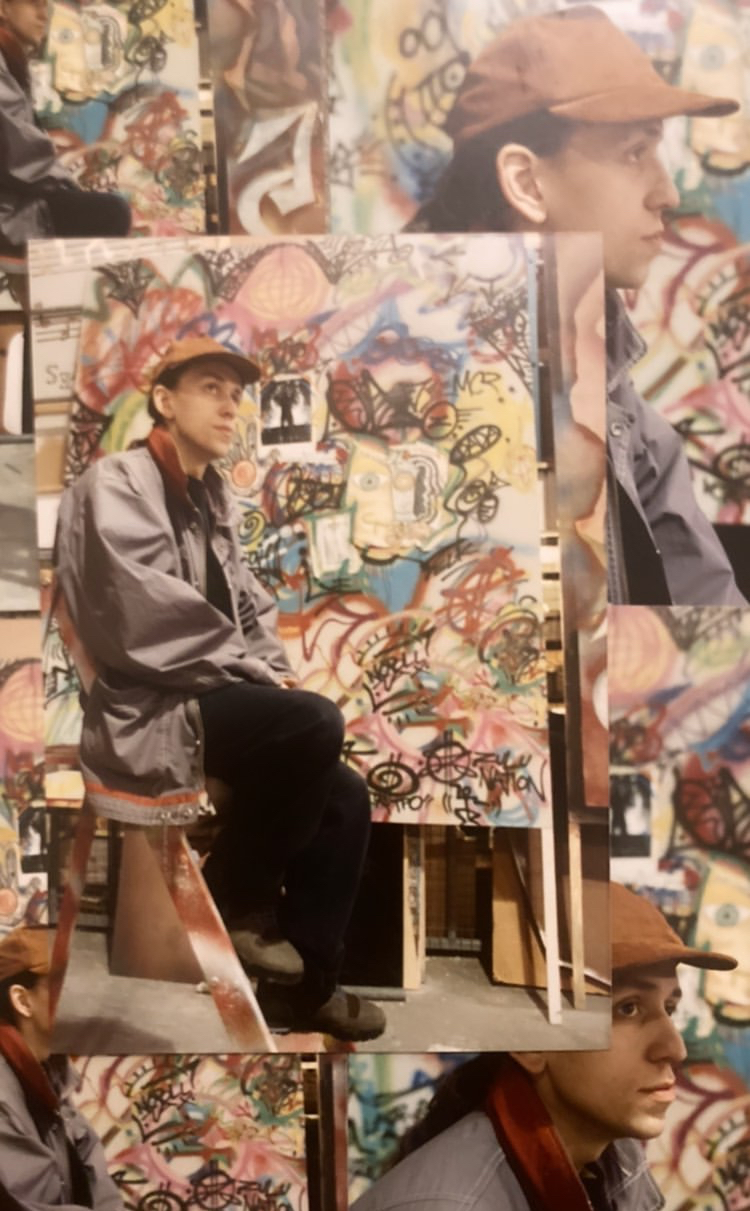

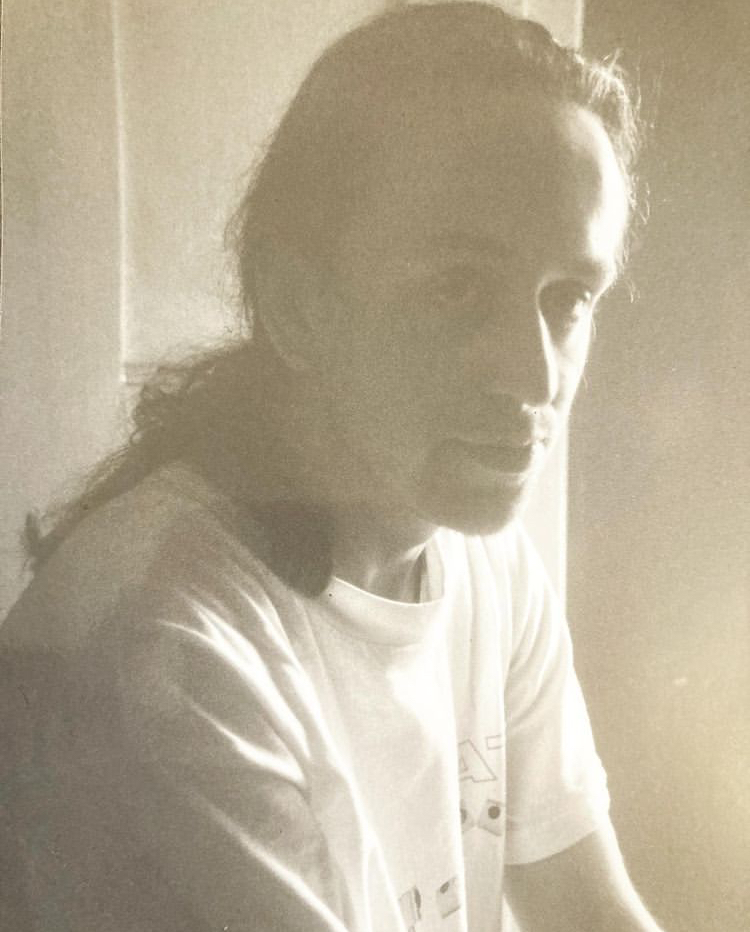

This shyly subversive man in his late 40s, with a grey beard and glittering eye, who signed to Mo’ Wax, the iconic trip-hop label, in 2001, and later released music on Will Bankhead’s Trilogy Tapes, left a lasting impression on me. Here was someone who could see things that other people could not. Black Lodge was switched-on, a true outsider artist who championed the counterculture from its classical beginnings to the contemporary present. We spoke about the work of 10 FOOT, TOX, Nico and Oliver Payne. His graffiti tag was painted onto the shutters of a carpet shop across the road and all over Manchester. The tags, he claimed, pointing out into the rainy night, were ley lines that worked on a shamanic level, roads that led to him.

There was a quality of vulnerability to Dan, which denoted the sacrifices one makes in a life committed to living on the jagged margins, upending yourself ceaselessly and forgoing trappings such as marriage and children in the pursuit of raw experience. This vulnerability matched a droll sensibility and tenderness of spirit, which reminded you of the rarity of meeting someone in the here and now who you could deeply connect with. Throughout the evening, he would often return to the notion that the self is unfixed; individuals can cut up their experiences to create art out of or live within.

Whilst this was the first and only time Dan and I met, we stayed in contact afterwards over Instagram. He was always interested to know how the documentary was going and sweetly kept up to date with my personal projects. Early last year, I received the sudden news that Dan had passed away.

Having haunted the seedier side of the north for almost five decades, searching for the light in the pouring rain, it felt unreal that he had left the world from which he had sifted so much experience. I was bereft that I had not said goodbye, that he would never hear the (still-unfinished) radio documentary, that we would never have the third bottle of wine we said we would have the next time we met.

Last summer, a few weeks after Dan’s death, still despairing from his loss, I travelled to Woolwich Works to experience the Dreamachine, a multisensory immersive experience comprehensively reimagined by Collective Act. This consciousness-altering spectacle was created in 1961 by William Burroughs, the artist, writer and inventor Brion Gysin, and mathematician Ian Sommerville as a stroboscopic flickering light art device that produces eidetic visual stimuli.

The device is traditionally made with a cylinder with geometric shapes cut into its sides, placed onto a record player with a light suspended inside, and rotated at 78 or 45 revolutions per minute. The device projects light at thirteen to eighteen pulses per second, corresponding to alpha waves in the human brain during wakeful relaxation. This can create a trance-like hallucinatory state akin to a psychedelic trip when you close your eyes in front of it.

Within the long-disused Woolwich Public Market, our group of thirty stowed our shoes and phones in lockers near the entrance. We were given a precautionary induction talk aimed at those with photo sensitivities and introduced to the Dreamachine’s history, along with its potentially consciousness-altering effects. We lay back on a reclining doughnut-shaped sofa inside an enormous octagonal room, the overheads dimmed, and we closed our eyes. The microcontroller lights above started dancing, slowly at first, then they picked up speed, sparring in rapid succession.

The light then grew in intensity, gradually casting soft fuchsia and azure blue forms that mirrored each other like a Rorschach test. Electrical-like auras pulsated around them, becoming more vivid, transmogrifying into sphinxes that multiplied and disappeared into the surrounding void. Tunnelling through this non-field of vision soon felt like an unreachable distance, an all-consuming centrifugal point that my mind urged itself towards. I felt as though I was witnessing simultaneous impressions of past lives, the more of which I experienced as I let go of the influence of the Dreamachine’s omnipotent lights.

Flowers began forming out of the ether, their petals dripping with brilliant colours, becoming outlines of skyscrapers and cathedrals that shuddered and slithered, melting away. Psychedelic graffiti tags appeared, names and words blurring beyond comprehension as though sprayed in real time by some faraway Oz, weaving a strange performative spell.

Black Lodge came to my semi-conscious mind as I gradually lost sense of my own body’s physicality in time and space. His presence penetrated the darkness and became imbued with the visual effect upon my consciousness. Traces of his early abstract expressionist paintings made in Berlin came to me from photographs I had recently seen; Matisse’s faces shifting into codified symbols and hieroglyphs that could have featured on an unreleased The Fall album cover. The unreal cityscape was simultaneously familiar yet deeply unknown. It felt exactly as it should have, a signifier of a lost future constructed from a densely rich past.

I cannot claim to have experienced anything resembling Dan’s own psychedelic trips that he took during his life; this is something insurmountably subjective and unknowable. Yet, by experiencing the Dreamachine, my mind felt like it drifted closer to his as the lights pulsated against my retina, travelling through overlapping rhythms of consciousness. Constantly shape-shifting and cutting up complex geometric forms, I was in a hinterland between reality and the unknown but would never reach the end of. It felt like a place where Black Lodge had been before or was journeying on his way out of life.

Describing a trip is like trying to articulate the effect live electronic music can have on your mind, which is to say- hugely difficult. Of the same ilk, this is a cerebral experience that connects you with parts of yourself that are often unreachable. Dan would have known this; his potted discography is notoriously hard to track down and define into anything like a collection or retrospective. One of his King’s Arms sessions features spoken word, distorted fever-dream bass, 1980s proto-techno, and a decaying rave tape he found in the Salford snow. His vision was open to many secret vistas whose existence no common eye suspects.

The evening in Woolwich and the one spent with him in Manchester now felt inseparably woven. Experiencing the Dreamachine felt as though it brought me closer to him and his sated connection to underground culture, hoisting me several rungs up the ladder I was already on. It helped me manage my sadness for his passing by understanding the ripple effect that a person’s life and death can create and how you can feel closer to that person by sharing a semblance of their own experiences, no matter how far away and far out you might find them.

Meeting Dan in Manchester instilled in me a tenacity that, despite having known him for only a small moment, we had broken bread together upon his uniquely curious quest. Whether by luck or serendipity or magick, Black Lodge would have considered all things as having a preternatural intention. Life was always going to be like this; you go in search on strange, unfamiliar roads and sometimes find others along the way who have gone in deeper, further, and even end up loving them for it, cherishing those encounters until the end. So it goes.

Darkness is undoubtedly imbued within Dan’s life and art, inseparable from his being and likely a force he would not have wanted to do without. I sometimes listen back to our recorded conversation at night. His anecdotes are often hilarious and punctuated strange truths; others ebb on the truly strange and frightening underbelly of life. Looking back now, my memory of meeting Dan now feels like a flickering beacon emerging out of a rich wellspring, above the greyness of a tall city, out of the smog of life, and into something altogether charged and mystical.

Andrew Finch is a curator, filmmaker and writer based in South East London. He curates Carousel at Photo Book Café, a film exhibition exploring contemporary themes within art and independent film.

Instructions for creating your own Dreamachine can be downloaded here.

Words by Andrew Finch