Wouldn’t it be great to live in a world where anyone could become an artist, and not only those who can afford it? That utopia might just exist: Norway. The Scandinavian country’s truly democratic approach to the arts means that it has established a funding model that is unique in the world, and allows anyone to have a creative career. Norway’s wealth, distributed among a smaller population, and high tax rates contribute to the generous welfare state that benefits the arts, but it’s also down to a socialist way of thinking and a general consensus that art and culture are a vital part of a healthy society. And that means they must be properly supported.

The UK, meanwhile, ranks as one of the lowest contributors in Europe when it comes to the figures of GDP contributed towards culture, at 0.3 per cent—despite the evidence that culture yields plenty of profit for the country. £409 million per year will go into 829 organisations and projects across England, in grants and funds awarded by Arts Council England, every year until 2022. It may sound like a lot but when you break it all down that’s the equivalent of £14 per person, per year.

In Norway, the scenario is a little different. Their pioneering approach to arts funding sees individual artists receive stipends from the government, alongside the more traditional grants and funding that goes towards museums, artist-run spaces and galleries. Almost all of the art scene in Norway is sustained by public funds; the commercial scene is relatively small, due in part to the fact that there aren’t many collectors in the country. However, the lack of a competitive market (such as the one that drives the art world in London) allows more freedom for artists to experiment.

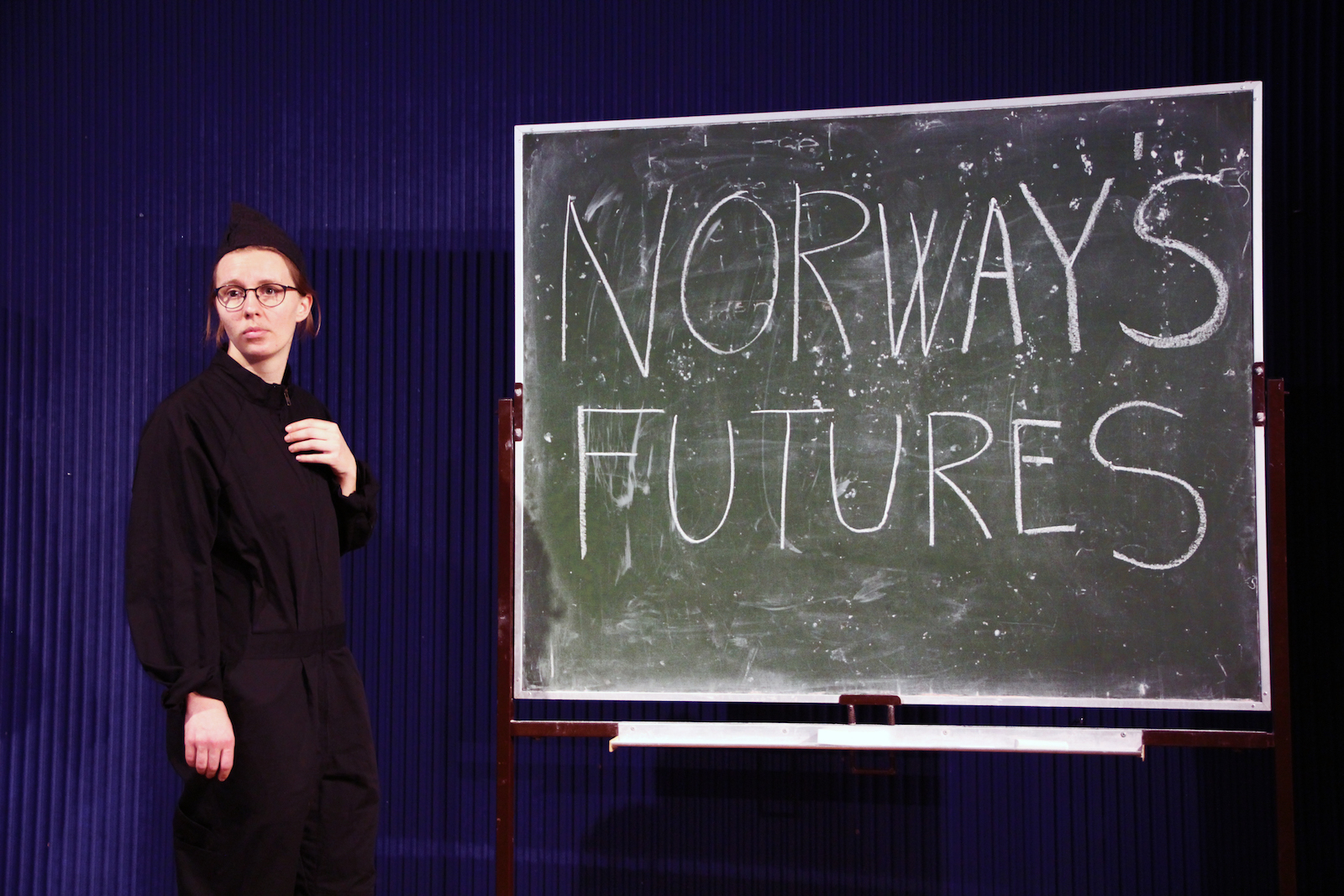

“Public funding of the arts finances many Norwegians who have committed their professional working lives to the arts,” says Per-Gunnar Eeg-Tverbakk, who alongside Eva González-Sancho is the co-curator of the new, five-year-long public art biennale, osloBIENNALE, that began this May in Oslo. The Biennale received 25 million NOK (£2,270,637.50) for its first year, and it is 100 percent funded by the government.

“My career includes positions at the Lofoten International Art Festival (LIAF); the Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo; the Nordic Art Biennial Momentum; and Artistic Interruptions: Art in Nordland—all of which are supported by public funding,” Eeg-Tverbakk explains. “While this means I am conscious that my practice and work may be held to account by the public, it has also given me an immense sense of freedom to experiment and explore,” he concedes. “I see part of my role as curator as finding a balance between connecting with the public and testing out new approaches to initiating, producing and presenting art in public space.”

“While I am conscious that my work may be held to account by the public, it has also given me an immense sense of freedom”

Putting that into practice, the first osloBIENNALE is an ambitious attempt to deconstruct visual information public spaces. “There is a lot of competition for viewers’ attention in public space. A look around the Central Station plaza in Oslo reveals an incredible amount of visual stimulation—in particular the advertisements—and reveals that public space is not really so public. It’s highly commodified and commercialised,” Eeg-Tverbakk continues. “Typically, urban spaces contains two kinds of information. The imperatives that tells you to buy stuff and the ones that inform you what is allowed in the shape of traffic signs: ‘Keep this speed’; ‘Go here, not here’. Public funding creates space for works of art that are open to interpretation and carry other voices, and I believe it’s fundamental to ensuring diversity of expression.”

The Arts Council Norway’s 2019 budget is declared as 949,5 million NOK (86 million GBP), with an additional 337,3 million (30.5 million GBP) for working grants for artists in all disciplines (including visual artists, authors, actors, dancers), awarded as an annual salary; about a quarter of the applicants for Working Grants are successful. Each application is reviewed by a jury of ten artists. The jury is selected in a democratic election, and changes every other year.

Anja Carr, an artist and curator based in Oslo, has received several different grants from the Arts Council Norway as well as Norwegian Artist Association and the Oslo Municipality funding body. Previously, she ran her own permanent space, PINK CUBE, in addition to her own practice. PINK CUBE is now itinerant. “I currently have a Working Grant from Arts Council Norway which means I get a monthly salary. For 2019, the grant amount is 268,222 NOK (24,300 GBP), which is the same as an average part-time position in Norway. But it could change next year, depending on the parliament’s budget.” Artists receiving the government stipend cannot be otherwise employed for more than 18.75 hours a week, or receive additional benefits.

Carr points to one major disadvantage of an arts ecosystem that relies on Norway’s generous and liberal-minded arts funding: political precarity. “The grants are constantly threatened politically and we have to fight for these rights that other artists before us have given us. We never know about the future.”

“Public funding creates space for works of art that are open to interpretation and carry other voices”

Working to protect the public money that artists receive, UKS (Unge Kunstneres Samfund / Young Artists’ Society) is a membership organization founded in 1921 lobbying for the social, economic and political rights of professional artists. Among their initiatives is campaigning for national art policies and outreach on contemporary art. Chair of UKS Ruben Steinum notes that in the capital, where development has been exploding and housing prices soaring, the local infrastructure has been put under significant pressure over the last two decades. “To solve this issue, the focus needs to shift from short-term thinking to a more wholesome and long-term understanding of the art ecosystem—and in that the importance of the individual artist and small and mid-sized art institutions,” he tells me in an email.

One of the most radical things about Norway’s current system is the fact that it allows anyone to be an artist. “You don’t have to come from a rich family to become an artist here. All the artists I know that receive grants work very hard. Culture is still just a tiny part of the government’s total budget,” Carr says. She is showing work at three exhibitions this month, including a solo show opening at Oppland Art Center in Lillehammer.

“You don’t have to come from a rich family to become an artist here”

Of course, receiving money from the public in this way could also makes you susceptible to public opinion. Are artists held accountable for the kind of work they produce? How much does the government bear down on artists and institutes, and are people disgruntled by it all? “In fact, a recent survey by Audiences Norway and Opinion revealed public funding of the arts in Norway is well supported,” Per-Gunnar reports. “Nearly 85 percent of Norwegians said they feel positive about art in public space—even those who do not share an interest in art—and 70 percent still believe the municipal government should fund it. Oslo Kommune [the city of Oslo] allocates 0.5 percent of its infrastructure budget to investments in and placing of art, which is generous and, as I understand it, unusual. This makes the funding model in Oslo very special and allows a certain amount of experimentation and risk not found in other countries.”

“While there is a growing sense of internationalism with curators and this undoubtedly feeds my professional life, working in Norway is special. The community is relatively small and there is definitely a Norwegian perspective that we share. I have two children and I am able to fully participate as a parent in family life because of the Norwegian emphasis on work-life balance and reasonable working hours and conditions.” Carr agrees. “I feel very lucky to be born in this country and be able to work full-time as an artist, but as long as I work hard and do my best, I don’t feel any responsibility when it comes to the content of my works. You can’t try to give people what they want. People want different things and art is meant to challenge and surprise, not necessarily to please.”