If you’ve visited an exhibition recently, you may recall seeing someone in the corner—most likely dressed in black—quietly observing the room. The role of the gallery attendant is rarely reflected upon by gallery-goers, and yet their watchful presence is as ubiquitous as the artworks themselves. Often working long hours, they are an essential labour force of the art world, as ready to engage in a critical discourse with visitors as they are to point them towards the loos.

The typical profile of the gallery attendant is art school graduate with big plans for the future. Many work part-time, allowing them to focus on their own practice outside of the job. “For the vast majority of people in the role, money is tight. They’re often trying to find their own studio, and are finishing or have just finished university,” an attendant at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts confirms. “And then you have the odd person who’s been there forever, and a few who have joined in retirement just to pass the time.”

Competition for gallery jobs remains fierce, and many in the role feel overqualified. “I applied for a temporary voluntary role and then was really pleased to get this job. It seemed glamorous,” a former attendant at Serpentine Galleries tells me. “When I started, I immediately found that the public were much more respectful and polite to people working in galleries than people working in shops—I’ve worked in both—and it must be the same people. It’s assumed that you have a higher level of education. It was depressing but a relief as well.”

Those in the role often form close bonds with one another, rooted in a mutual understanding of the ups and downs of the job. “One of the main pluses of the whole experience was the cliquey camaraderie with the other attendants,” one recalls. “Your breaks would be at the same time as one other person and it would be like a date with them, where you got to know them really well. It’s a long day on your feet, really gruelling. I’ve never smoked as much as I did in this job.” A former attendant at an international blue-chip gallery agrees: “Everyone’s got something to complain about, which is such a conversation starter working at commercial galleries—you can always bitch about someone from sales.”

“I think of the job as a bit like when people do those silent meditation retreats”

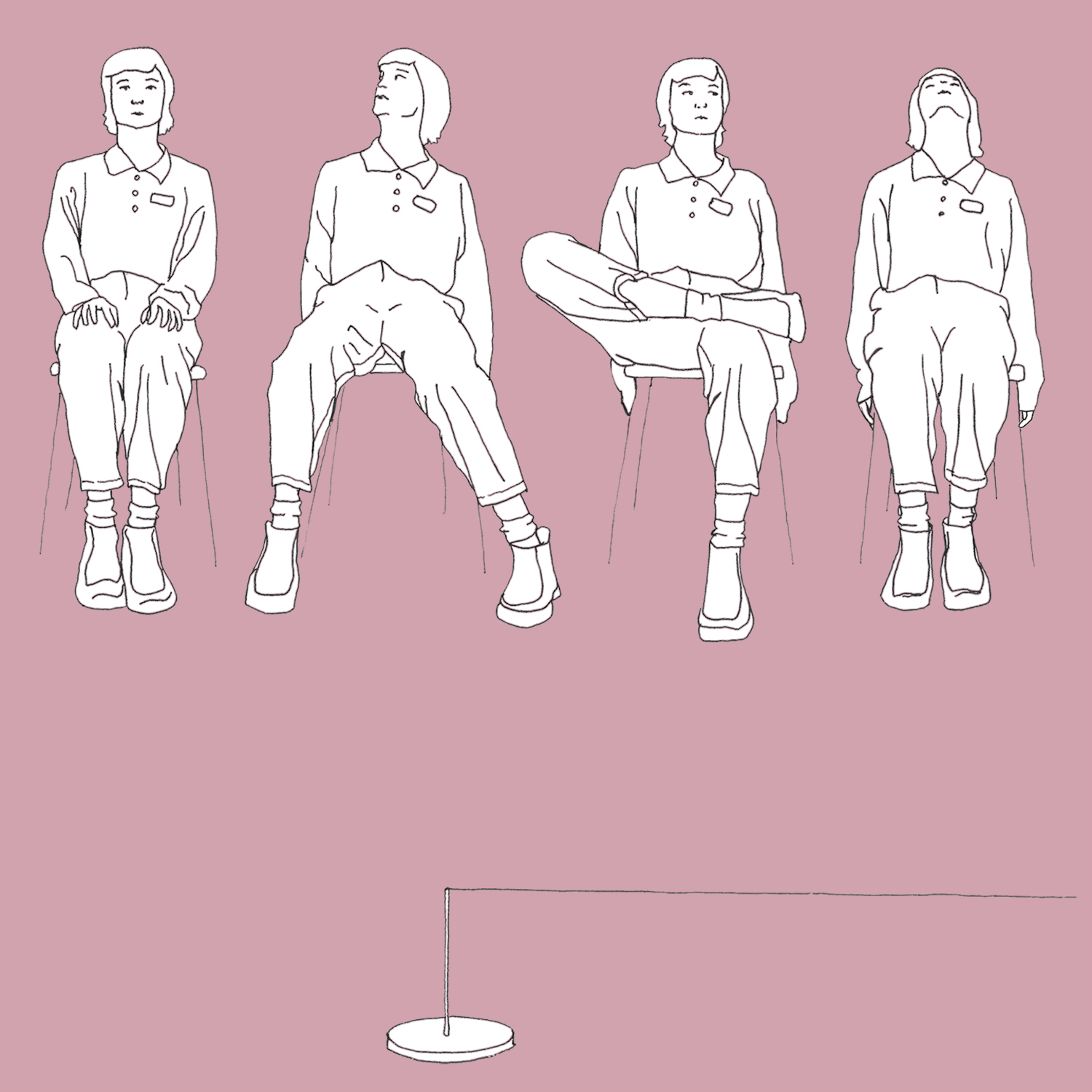

Most gallery attendants I spoke to explained that reading was not permitted on the job. For some, sitting down or leaning against walls was also not allowed—at one London gallery, through union campaigning, the attendants were granted one seat to share between them. It raises the question: with long hours and nothing to do, just how do you pass the time? “I remember trying to repeat and memorise bits of French vocab and grammar. I also counted the floor tiles, really cliched things like that,” one former attendant recalls. Another reflects: “I think of it as a bit like when people do those silent meditation retreats. You watch people and create stories for them: some you really hate and others you love—your brain plays tricks on you.”

All attendants point out that the experience is above-all influenced by the exhibition that you happen to find yourself working in. “If you had a show with no natural light, that was the worst,” the former Serpentine Galleries attendant remembers. “The Ed Atkins show was torture, absolute torture, appalling to work in. I like his work, but just imagine spending a full day in the show…” An attendant at South London Gallery agrees: “The worst thing is short looped videos, they really make you go insane.”

Hidden away in the dark, it is easy to feel invisible—although even brightly lit exhibitions can leave attendants feeling ignored. “I’ve felt a lot more invisible here just because we have to wear a uniform and we all look the same,” a Tate attendant asserts. “There’s also so much to see and do that, unlike at a lot of commercial galleries, people don’t have the time to ask us questions about the exhibitions. It’s more like working in a theme park than a gallery.”

“The worst thing is short looped videos, they really make you go insane”

However, when visitors do engage with staff, the experience can be rewarding. “Especially with elderly people, they often have experiences in their life that they can relate to the artwork,” a current attendant at White Cube explains. “I think that exchanges between young and old are something that usually happens within your own family; it doesn’t often happen on the street, and this is a rare space for it.”

At larger galleries, it is more common to encounter audiences who are not necessarily interested in art at all. “I see people with Hamleys shopping bags from Oxford street, loads of tourists coming in,” the attendant adds. “But also, the White Cube architecture is very Tumblr-esque, it’s very Instagrammable, very visually pleasing. People like to take pictures of themselves in the space, and they’ll do multiple poses—like on one leg.” An attendant at ICA confirms: “Any piece that has a mirror will inevitably get Instagrammed, but that’s probably more telling of society than the work.”

Next time you take a snap of yourself at a show, it might be wise to take a moment to acknowledge the constant presence of the gallery attendant, stationed quietly in the corner. Spare a thought for the long day ahead of them. It might be easy to feel intimidated in the pristine surroundings of a gallery, but it’s valuable to keep in mind that many of the staff are more open to conversation than you might think. As one attendant concludes, “I’m very much of the belief that galleries shouldn’t be silent white cube spaces; they should be places for discussion and to share ideas.”