“Sometimes we lose love and then we lose our heads. We stare straight ahead and cross the road without looking”

Love is crossing the road and not having to look both ways, or so a friend said when we were sixteen. She had been in love and I hadn’t. I was curious, of course, and when probed, that was her insight into how love feels. I was confused, naturally: crossing the road and not having to look both ways? Surely that’s madness. A death wish at most and dangerous at the very least. What she meant was that love lends you an extra pair of eyes, that love has your back. As I went on to fall in love, I learned that all of this was true: love offers support, often it is madness and sometimes it is dangerous.

Take, for example, Chris Kraus’s I Love Dick, a story about her love and infatuation with Dick Hebdige, which sits somewhere between fiction, essay and memoir. After having dinner with Dick, “an English cultural critic who’s recently relocated from Melbourne to Los Angeles”, she “can’t stop thinking about last night” and proceeds to write him letters, increasingly obsessively as she falls deeper and deeper into her passion. Letters put feelings onto paper, externalize our internal state in an attempt to communicate the truth of who we are. French artist Sophie Calle asked 107 women to interpret a break-up letter that was sent to her by an ex-boyfriend, which resulted in her French Pavilion installation Take Care of Yourself (2007) at the Venice Biennale. Bemused by its tone, she approached female friends to garner their opinion on the letter with the aim of helping her to respond. This snowballed, and soon she was approaching professionals (crossword writer, opera singers) to deconstruct the letter and reinterpret it using another language—their language. Did it help her to further understand the letter or how to write back? Perhaps so, perhaps not. It is testament to our societal investment in emotion, a shared language in which we all have experience, so that we might come together to lighten the load of love’s weight.

Before I’d been in love, I imagined the emotion to be a constant state of joy; sheer ecstasy that lights up everything under a glowing beam, rainbow rays being emitted from your eyes to bathe the world in wonder. Slushy. And at moments, it is this. I’ve been so enamoured by love that I’ve missed a long-haul flight to Australia because I couldn’t see past my feelings to look at a clock and cognitively process the necessary timings for check-in. I’ve also been so consumed by the loss of love that I’ve felt forlorn for months. Heartache. Sometimes we lose love and then we lose our heads. We stare straight ahead and cross the road without looking. Most of us will have felt all of these extremes, because that’s what being human is.

“Love is a sensorial awakening of racing heartbeats, of shared breath and sweat”

At weddings, we celebrate love’s brilliance. We choose love poems that reflect our best feelings—no one wants to hear a recital of how haggard love has, at times, made us feel. We collude in a moment where love equals perfection, where love is crossing the road and not having to look both ways. We tune into our good times together and tune out the bad. For these occasions, we rummage through our bookshelves, choose love poems that melt through it all. There are the favourites: TS Eliot’s A Dedication to my Wife speaks of lovers’ bodies becoming one:

To whom I owe the leaping delight

That quickens my senses in our wakingtime

And the rhythm that governs the repose of our sleepingtime,

the breathing in unison.

Of lovers whose bodies smell of each other

Who think the same thoughts without need of speech,

And babble the same speech without need of meaning…

Love is a sensorial awakening of racing heartbeats, of shared breath and sweat. If we let words melt into form, it might conjure the sculpture of August Rodin, whose Metamorphosis of Ovid (1886) sees two women embracing, arms and legs entangled as hard marble becomes soft flesh, fingers sinking into tendrils of hair, faces merging, bodies absorbing one another. Critics of the nineteenth century shied away from discussing the work for its sheer eroticism. Keep melting, and now meander forward in time to the late-twentieth century: what would they have thought of Jeff Koons’s project Made in Heaven (1990)? Comprising billboard posters, photography and sculpture, Koons depicted his sexual relationship with his Italian porn-star wife, Cicciolina. Blurring the boundary between fine art and pornography, their explicit, glossy, glamorized poses capture them having penetrative sex, bringing into question conventions of taste and the role of sexuality in visual culture. Today, we see sex everywhere and flesh is used to push products: sex sells. Koons taps into this space, one of love, sex and bodies as shiny perfection, though lured into a realm of fantasy, with butterflies, pink backdrops and bronzed rocks to mythologize the physical aspect of love.

Bodies have merged throughout the centuries, to differing effect. An evocative ode to this is found in Ali Smith’s book Artful, where she describes lovemaking in relation to landscape—body, earth and air becoming intertwined:

I thought how somewhere at the core of this lovemaking I had sometimes known, understood for a moment, what goes on at the core of the earth down through all the roots, past the taproots, way down through the layers of cold to the layers of heat, right through to platelet level. I thought, too, how at exactly the same time as going this deep I could understand any huge bell hung high in a bell tower, hollow and full, stately and weighty, as high in the air as a bird, beginning the slow ceremonious swing of itself against itself that means any second the air is going to change its nature and become sound.

It was a place that could only be reached when you were brave enough to come into yourself so wholly that you left yourself behind.

It was a place I missed. I had no idea how to get back to it. I had no idea if I’d ever see it or be in it again.

Being with another, letting your bodies become one, allows access to a space that isn’t accessible alone. Losing this equates to a form of isolation—from being able to access yourself—closes the door to a space that might be locked forever. How might it feel in our memories, as an idea; can we ever conjure it fully, reproduce it, concretize it? As Alain Badiou says in his short book In Praise of Love: “Love cannot be reduced to any law. There is no law of love… just as when you tell someone, ‘I love you’: you say that to someone living, standing there in front of you, but you are also addressing something that cannot be reduced to this simple material presence, something that is absolutely and simultaneously both beyond and within.” So love permeates our bodies but exists somewhere beyond us, an immaterial presence that finds form in our words and flesh for just a moment.

“I see one lover slowly being consumed by nature and the other looking on blankly”

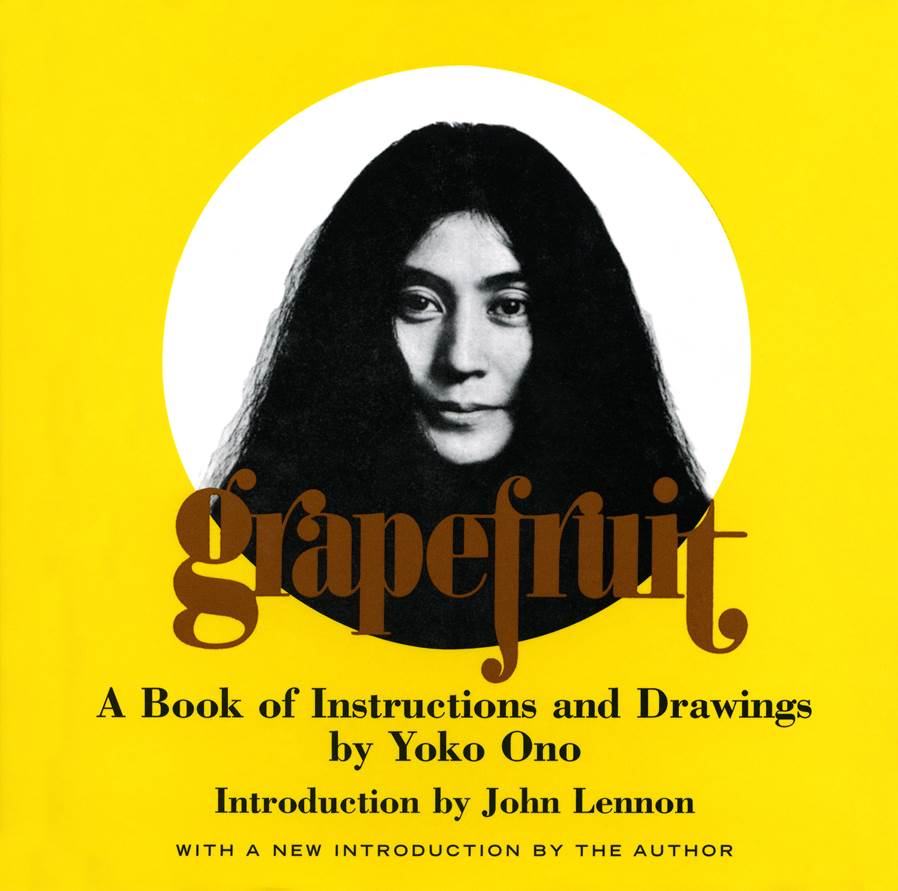

It’s not necessarily about love per se, but Yoko Ono’s Snow Piece, from her book of illustrations and drawings Grapefruit, makes me think of love, imagine love:

Think that snow is falling.

Think that snow is falling everywhere

all the time.

When you talk with a person, think

that snow is falling between you and

on the person.

Stop conversing when you think the

person is covered by snow.

1963 summer

I read it and envision scenarios where lovers walk, talk, stop and stare. I see one lover slowly being consumed by nature and the other looking on blankly. Perhaps as one disappears, the lover is snapped out of a trance and digs frantically to recover the other. Perhaps they are lost forever, or maybe they find them, breathe on them and slowly let them thaw. Returning to Sophie Calle, her Pas Pu Saisir La Mort (Couldn’t Catch Death) tries to capture breath. In this video from 2006, the artist placed a camera at the foot of her mother’s bed to capture her last moments of life on film. She wanted to be there to hear her last word, to seize her last breath and let it play out forever. After all, when we love someone, we don’t want it to end.