Bodily forms are found in abundance in nature and botanics. A draped leaf recalls curvatures akin to the swoop of a brow; a fresh shoot from the ground could just as well be a fingertip emerging from below. It is a symmetry that is hardly surprising given our shared roots on this earth. For we are dust, and to dust we shall return. Or perhaps, as humans, we are simply bound to see the world as an eternal reflection of ourselves.

Certainly, there has been no shortage of comparisons between the female body and flowers in the history of art, from Georgia O’Keeffe’s sensual paintings to the sexually explicit photography of Nobuyoshi Araki. But the male form is less frequently evoked by artists through nature.

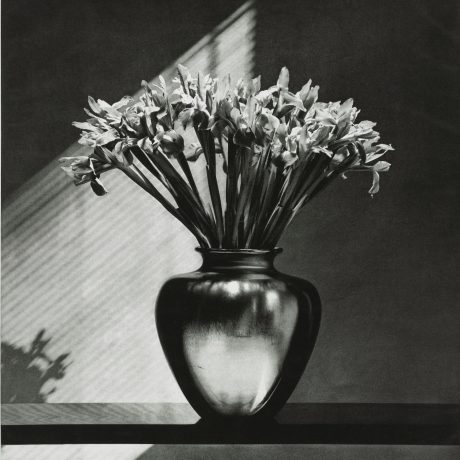

For Robert Mapplethorpe, the flower became an extension of the forms that he framed and photographed in his nude portraits of men. During the late-1980s, he photographed numerous plants and cut flowers in his signature black and white on medium format.

“A draped leaf recalls curvatures akin to the swoop of a brow; a fresh shoot from the ground could just as well be a fingertip emerging from below”

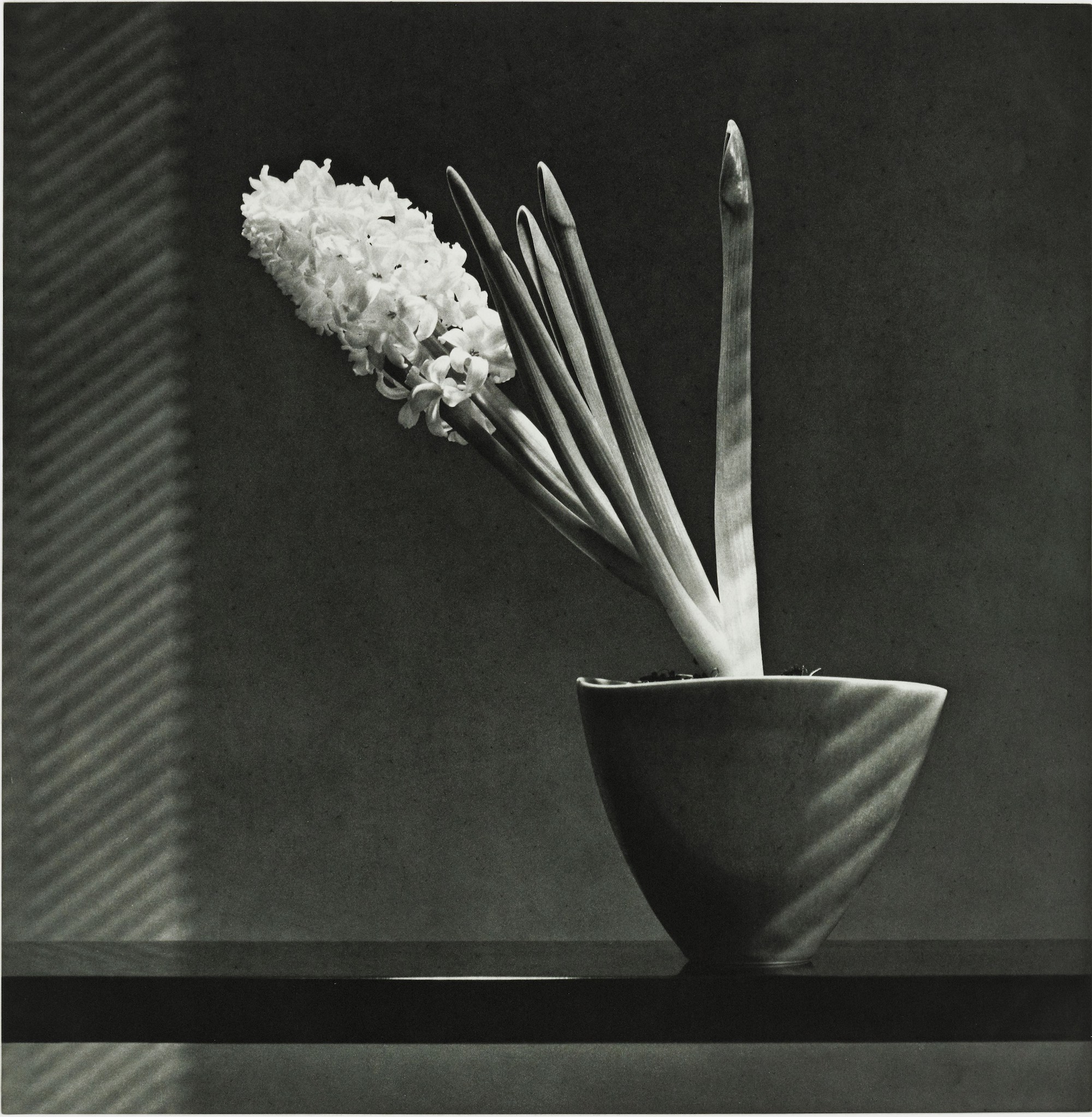

Hyacinth, shot in his studio in 1987, brings tenderness to the still life. A single stem emerges in the frilly array of bloom, lopsided and tumbling to one side. It is as if the fullness of yearning had afflicted it. Just one stalk of the plant stands upright, its sexual connotation clear. Natural light from the unseen day streams through the window, casting a shadow through the blinds—as if to suggest a surreptitious moment just removed from prying eyes.

This image was captured just two years before Mapplethorpe’s death from complications related to Aids. The loss of his partner and patron, Sam Wagstaff, the year this image was made led Mapplethorpe to reckon with the reality of the infection in his own body. He would have been aware of how little time he had left when he took this picture.

In this knowledge, his focus on the transient natural world carries new poignance. The single, blossoming hyacinth looks perfect, but has already begun to droop ever-so slightly. The decay that would come next is inevitable, defied only by the click of Mapplethorpe’s camera shutter. In front of his lens life stands still, offering momentary respite from the endless march of hours, minutes, days.

Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith: Flowers, Poetry, and Light

Selby Gardens, Sarasota, until 26 June

VISIT WEBSITE