Lydia Eliza Trail speaks to Tobias Bradford about his eerie, twitching, works of art.

The automaton is a perverse little machine. While it takes the form of a human, its movements can only approximate the soul. Still, in its imitation of being, the machine can manipulate our emotions. We feel sympathy, pity, and pathos – against our better nature. I speak to Tobias Bradford, an artist who uses the automaton as his primary medium, on the occasion of his exhibition As My Eyes Adjust at Company Gallery New York. We discuss his creations, delicate beings that twitch before our eyes.

As My Eyes Adjust originates in Bradford’s 2019 degree show at Goldsmiths College of Art, London. At the time, he was interested in the occult practices of the early 20th century. In Spiritualism, a movement that saw the rise of mediums offering encounters with the paranormal, elaborate theatrical setups were built to engender a willing suspension of belief in the audience. “It’s that line between fact and fiction which interests me”, he elaborates “Spiritualism, magic, and illusionism went hand in hand; it was still considered a kind of science”. Spiritualism Exposed (1926) is the origin of his title: As My Eyes Adjust. The film features a long, drawn-out scene of disembodied hands emerging from darkness to entertain an Edwardian audience. At one point, the lights are switched on, and the phantasmagorical presence in the room is revealed to be a man waving things around with a long stick. “It’s the flick of the switch. The reveal, that’s where the title came from. Your eyes adjusting to the light. I found that reveal funny, you know – pathetic in a kind of endearing way”. Watching the sculptures convulse on the gallery floor, it seems the artist has projected the pathetic, endearing quality provoked by the farcical reveal of Spiritualism Exposed, onto his sculptures. The artist grants his creatures existence despite, even because of, their faults.

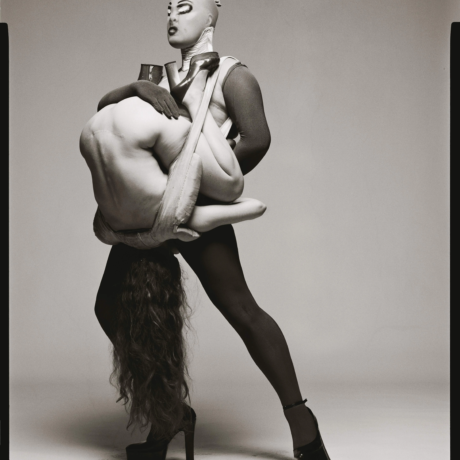

Bradford’s contemporary audience is not dissimilar to those of the Spiritualists; both choose to suspend belief for a chance to encounter the titillating macabre. In the basement room of Company gallery are three animatronic sculptures: Joints creak like tectonic plates (2024), Nude Figure (2024) and Dog (2024). These works do not interact with one another; their only source of comradery are erratic, janky movements and an inability to achieve a fully animated status – like a broken record, or a clock hand stuck on a minute marker. Dog (2024) is the body of a headless mammal lying on the floor. It’s proximity to death, or the act of dying, is unnerving. The sculpture’s ‘breath’ is ragged and shaky, conveyed by an accordion-like device that pumps up and down as its legs spasm. There is a slippage between puppetry and stop-motion in its movements, which affords Bradford’s works a lively awkwardness that recalls the Czech surrealist animator Jan Švankmajer.

For this show, Bradford refers to – if not cyberspace – a science-fictional universe in which our avatars, far from being a perfect version of ourselves, are the physical manifestations of our anxieties. In the work OUTSIDE (2024), a light-up LED screen reads, “Sun beaming straight into my Wide Open Eyes. I have touched the grass, and I have allergies”. The digital glitch is more familiar than the broken clock hand in our everyday reality. Bradford’s work has not been examined for its relation to Legacy Russell’s seminal text, Glitch Feminism (2020). A glitch in cyberspace reflects the imperfect – the broken and non-useful. Russell extrapolates the glitch as a site of political dissent – “a much-needed erratum” and humanising correction to the late-capitalist machine. Bradford’s interest in reducing the human form to a repetition of an action, paired with his use of non-accelerationist materials; springs, wood and basic motors, can be seen as a physical expression of Russell’s liberatory glitch.

The interiors of Vegas casinos influenced the windowless basement room that houses Bradford’s works. Within their vast interiors, rooms (or halls) are often decorated as if they were the outside world, presumably with a vested interest to keep their occupants inside. The use of AstroTurf as flooring at the gallery is lifted from Las Vegas’s famous underground house. While described online as a “Luxury cold-war era home”, really, it’s a bunker with soft furnishings. Built in the 1970s by Jerry Henderson, director of Avon products, the rooms mimic world construction in The Truman Show (1998). Its picket fence contains painted vistas, the garden furniture, all that distinguishes the “inside” from the “outside”. In imitating these spaces, As My Eyes Adjust creates a feeling of campy agoraphobia.

“Childhood is really quite scary and uncomfortable at times, both wondrous and terrifying” Bradford explains how he references childhood play: “As children, we don’t really make the distinction between subject and object; that distinction is developed later in life”. The works recall the crude animism of a child’s imagination. As if a child is crouched in a corner nearby, unable to distinguish the animate and inanimate, projecting life into the works.

I ask Bradford if he ever feels like he’s playing God. “I like when a work surprises me…when I allow it to live its own life, succumb to its own entropy” as stated in the second commandment, to create in God’s image is blasphemous; “The idea of breathing life into a machine, it’s very self-indulgent, and perverted”. Bradford’s machines do not feel self-indulgent, far from it. Rather, they meditate on the pain of humanity and existence. If anything, the weight of their existence is put upon Bradford; the sculpture’s sense of self – aside from their indefinite twitching – is unknown.

Words by Lydia Eliza Trail