Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

Out today on Artsy is Olivia Giovetti on Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Harvesters.

I’ve developed a few debilitating phobias in recent years. The big one is confined spaces. Riding the train or walking through an underpass can cause my face to flood with heat and my brain to dislocate from my body, petering out into tiny splinters. My panic attacks have always had a psychedelic quality to them. None of this heart beating and palm sweating stuff. More just death and I, wrestling in a spiral of chaos.

I’m fairly confident that these phobias were already present in my mind before stepping into the halls of the Palais de Tokyo

two winters ago, but I can’t say that they weren’t further exacerbated by the experience. I was there to see a one-man show, On Air, by Argentinian artist Tomás Saraceno. Walking from the 17th Arrondissement, where I was staying with my friend Margaux, the gallery and the Eiffel Tower opposite were both submerged in a dense fog. It was a cold morning, and the vast art deco steps to the gallery were empty. I’d had two strong coffees that morning and my heart was beating fast.

“My panic attacks have always had a psychedelic quality to them. Just death and I, wrestling in a spiral of chaos”

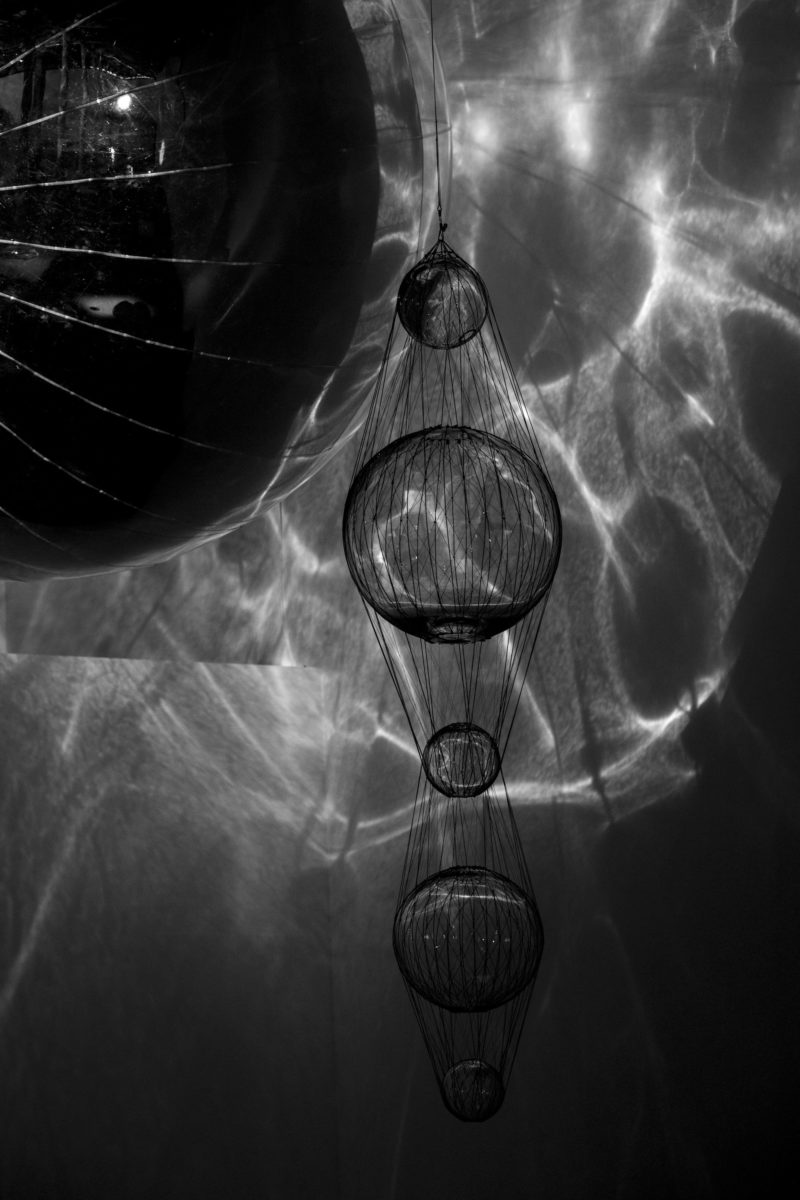

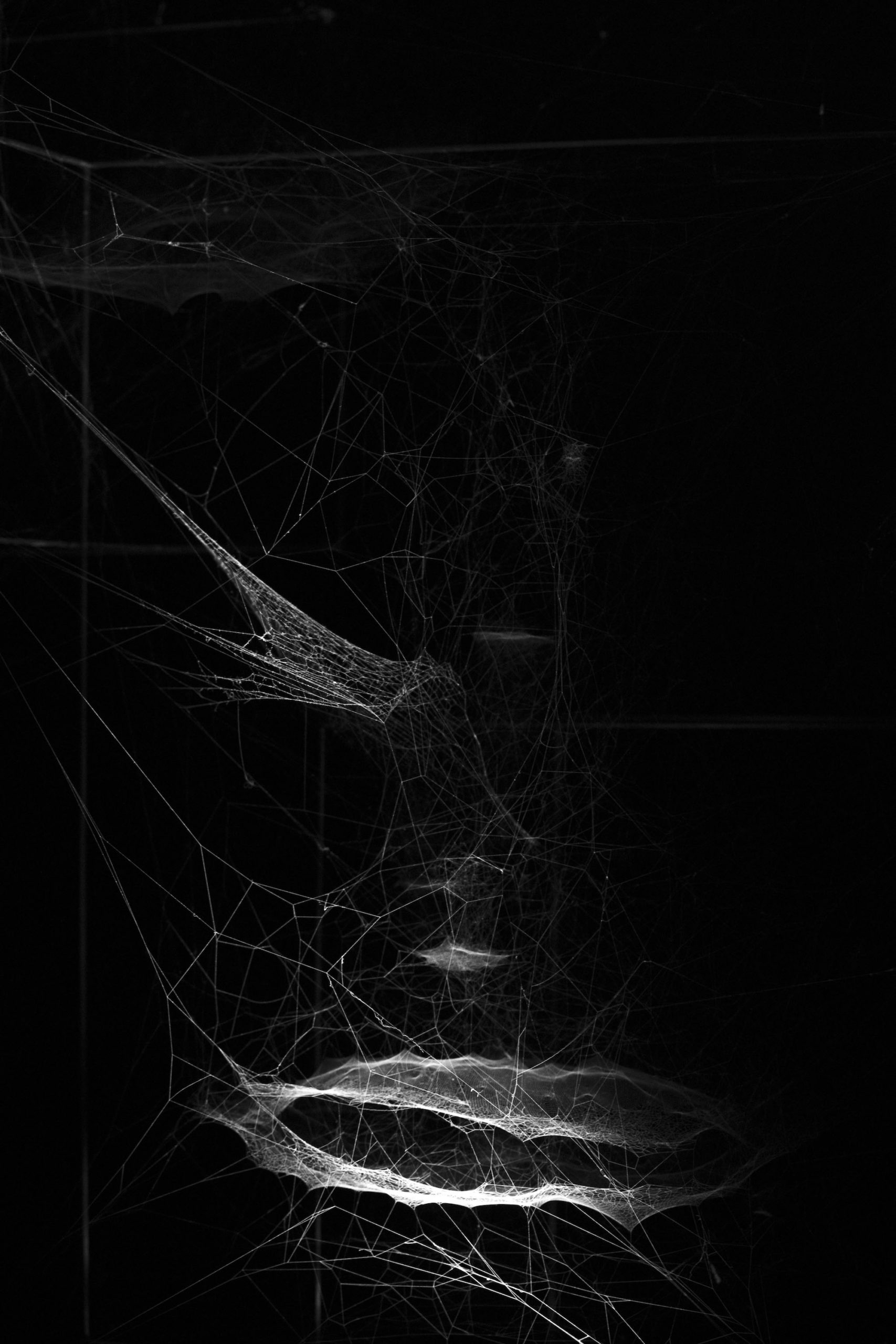

The first room of the show was lined with black curtains. Dim, UV light made it difficult to see. Inside were several large cuboid frames without glass, in which different species of spider had been left for a period of a few weeks. In that time, they had each created elaborate webs, some several metres high, each species weaving a pattern distinct from the last. Some had built what looked like dense burlap, while other webs appeared more flower-like and fractal.

From far away these installations looked like laser-cut designs through glass, or maybe formaldehyde. But it was only by getting up close that you could see they were constructed from fine strands of silk, gently wafting on the exhalations of the visitors who piled in to gawp at them. The room was big, and as you walked, more of these strange sculptures came into view. In the middle was a larger frame than the rest, whose web had been spun with a thread so delicate that its cumulative impression was that of a cloud or a vapour suspended in the middle of the room.

The parts of the web that had been spun more densely created delicate planes of materiality that transformed under the light—invisible one minute and then glowing, halo-like the next. It looked like a Turner painting, whose skies always seemed to me to be made of a thin gauze. Around this structure, a small crowd had gathered, many of whom were in their seventies or eighties. It was odd, the group of us standing there, in the centre of this city where we would otherwise be burrowing between the Haussmann boulevards and thinking about nothing but our next appointment, or what we might be having for dinner.

Me and several old men and their wives with severe grey haircuts, Miyake silhouettes and Balenciaga trainers, as unyielding and unsentimental as the Philippe Starck restaurants

they would soon be retreating to to discuss the whole experience—”C’est bizarre!”—and yet staring, open-mouthed as if they were five years old. Their master, a two-centimetre arachnid from the Amazon rainforest, lolloping between the vast canopies he’d created for himself in this, one of the most respected contemporary art galleries in the world.

A man, with a tanned head protruding from a zip-up roll-neck, leaned in and pointed out something to his partner, finger nail skirting dangerously close to the web. He pulled it back as if it were the crown jewels of England, coy and remorseful for his encroachment on the artist and his precious work. “Pardon”, he whispered, before saying something indecipherable to his companion. Perhaps he was discussing the way that the spider pedalled its long, golden legs after arriving at a safe resting point, spinning more of its silk to bind the fibrous beams of its vast palace.

We stayed there for several minutes, all of us, doing nothing but watching as the spider continue its work and watching as our own flutters of breath, our coughs and our conversations disturbed the integrity of the structure. When eventually we prised ourselves away, I walked around the rest of the exhibition, an assortment of seemingly disparate objects and installations.

“I turned back, thinking about the quiet rhythms of the ecosystem that keep us all here and keep us all alive”

A single thread of spider’s silk stretched over several metres, in front of a microphone that filled the gallery with the melody of its gentle reverberations. Crystal galena radios, like those used in World War Two to intercept messages—a copper coil wound around a large amethyst and wired up to a pair of headphones—exporting me to a conversation between a man and a woman somewhere across the city. A live map of the air currents encircling the globe; air from Mumbai being converted into black pigment to make drawings on a vast, white sheet of paper. At the end of the exhibition, a huge, artificial spiders web had been constructed for visitors to walk through, their bodies striking the various fibres to create loud, harmonious echoes that served almost like a conversation between us.

The image of the web was still at the forefront of my mind as I made my way through the gift shop and finally towards the exit, with only a thought for how much we had lost through modernity, as well as the obvious and inescapable gains. I took a walk to the Bois de Boulogne, where the queue to enter the Gehry building extended far along the path (apparently an Egon Schiele exhibition).

I turned back towards the small antiquated fairground nearby, desolate and out of use until the warmer summer months, while thinking about the quiet rhythms of the ecosystem that keep us all here and keep us all alive. At the carousel I stumbled across a giant rat orgy—hundreds of the fuckers scuttling past one another and squeaking at the top of their lungs—worrying about how I was ever going to get home to London. Suddenly, a high-speed train, fifty kilometres below the seabed, seemed so obscene and so unthinkable.

All images: Tomás Saraceno ON AIR, solo exhibition at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2018, curated by Rebecca Lamarche-Vadel. Courtesy the artist; Andersen’s, Copenhagen; Esther Schipper, Berlin; Pinksummer Contemporary Art, Genoa; Ruth Benzacar, Buenos Aires; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York. © Photography Studio Tomás Saraceno, 2018

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life.”

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Harvesters

READ NOW