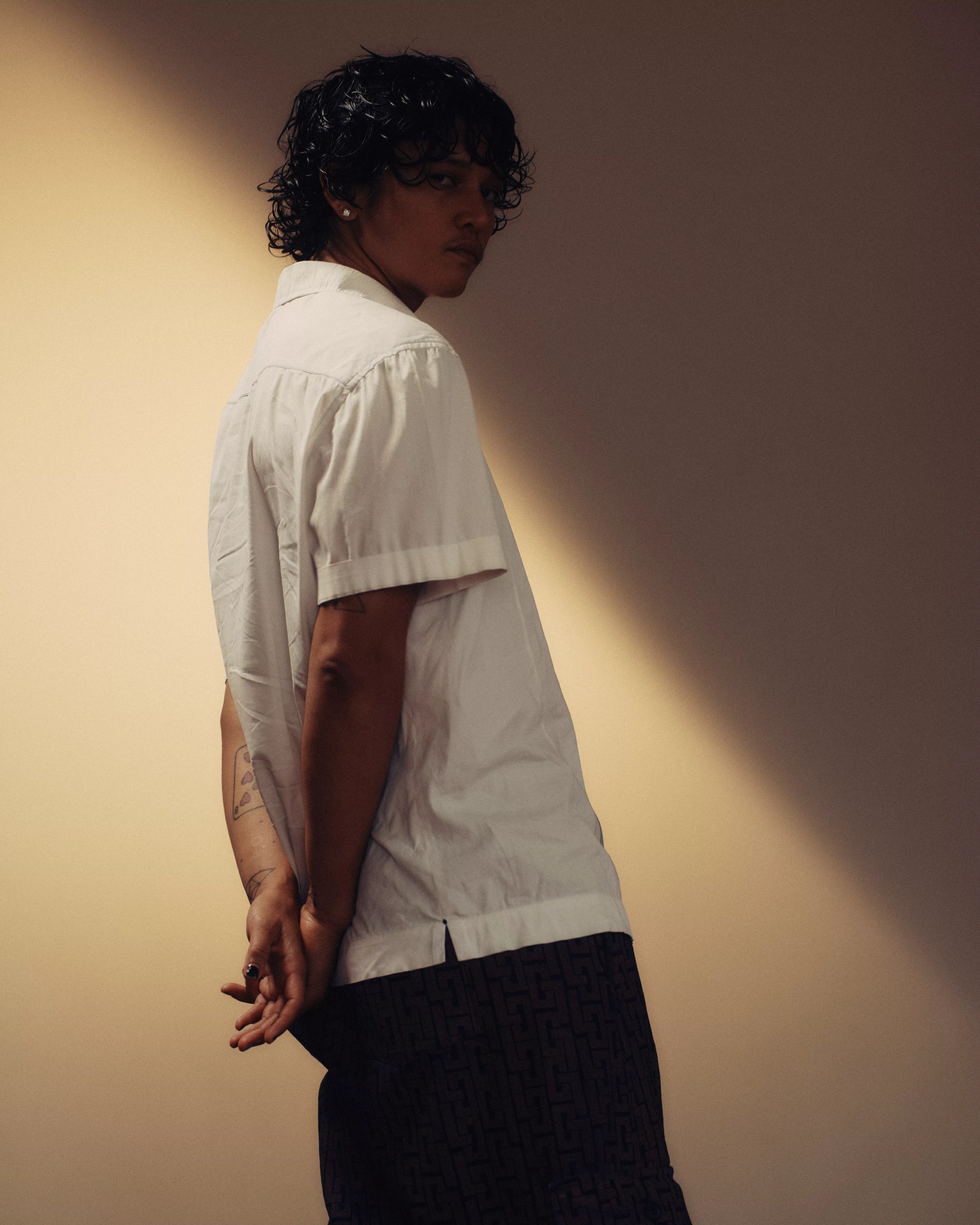

Meka Boyle speaks to Tosh Basco about her multidisciplinary practice which captures moments of physicality beyond the moment.

“I’m constantly trying to work through what it means to be alive right now,” says Tosh Basco. Basco is an inquisitive artist who came into her multidisciplinary practice on a stage — her body is a conduit for her vision. In recent years, she has begun exploring ways to remove herself physically from her work, while leaving traces, indentations, and marks behind on canvases. The results are emotive, abstract artworks that are a stand-in for the artist herself, an extension of her performance practice.

Basco is constantly evolving as an artist. In recent years, she has expanded her practice across mediums in search of new ways to capture concepts of physicality beyond the moment. Gestures from dances are memorialised on paper (her first paintings happened in real-time, as she moved her paint-covered body around the soon-to-be canvas), and physical markers of space are uprooted and re-contextualised in frames.

At the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai, Basco’s drawings and paintings hang on the walls, are suspended on glass, and rest on plinths. “They’re alluding to bodies,” says Basco. “When I think about a body that’s lying flat, I think about death and I think about rest.” Basco’s inclination towards a cosmic entanglement is at the heart of her practice: at Rockbund, the artist’s body is both within and outside of the room. It is the artist’s first solo museum survey.

“For many years, I felt the most comfortable and grounded with the ephemerality and the immediacy of my body being physically present in a space,” says Basco. “I think for some people, performance can be kind of ungrounding, because everything happens in the moment. But for me, I actually have a lot of control in that space because of my experience, and I feel most comfortable with it. It feels really good to get to share these different parts of my work that I think some people don’t know are all connected.”

In a photograph on display at Rockbund, untitled (no sky), 2023, a sky dotted with white clouds above a navy blue sea peeks out through white translucent outline of hands that stretch out to the horizon. Elsewhere, a body print made from professional clown paint is framed on a wall, and a gold, multi-armed deity-like painting appears to have been made by the artist repeatedly spreading her body across the white paper. In another work, scrawls of indigo allude to a hidden language. A large, abstract blue work on the first floor is a sum of its parts, refracting the movements that reverberate through the exhibition in a swirl of colour and gestures; at any moment its tendrils seem like they could jump off of the white canvas and dance across the floor.

Feelings are a prominent conduit in Basco’s work. Love is the message. “Emotions are socially constructed; colours mean different things in different places,” she muses, “but I think when you see hand marks scrawled, or a body print, or a photo of the sky: those are things that lots of people can relate to in one way or another.”

Basco is constantly using her art to channel the ineffable: a steady stream of creative output. Her next solo show will be at Company Gallery in New York in September. She is also working on two theatre productions with Moved by the Motion (a collaborative ensemble that she started with Wu Tsang in 2013) set to run at the Schauspielhaus Zürich starting in May. One is an interpretation of Georges Bizet’s iconic opera “Carmen.” Basco and her collaborators have been thinking about the tumultuous (oft-misunderstood) story of love and obsession for the last five years.

At Rockbund, the floor is made of blue Marley, a material used for dance floors and stages as well as in Basco’s own studio where she rehearses and makes her art. The artist’s first paintings she ever did were on Marley in 2015 in response to a desire to take the stage home with her after she performed. “Performance is something that each of us in the world do,” Basco says. “Hopefully, the floor allows people to see the architecture of the museum — the history of the museum — as a stage, and maybe think through the different places in the world as different kinds of stages: how we move those spaces, but also how we can confront those things, especially when we think about systems of power and who has access to space.”

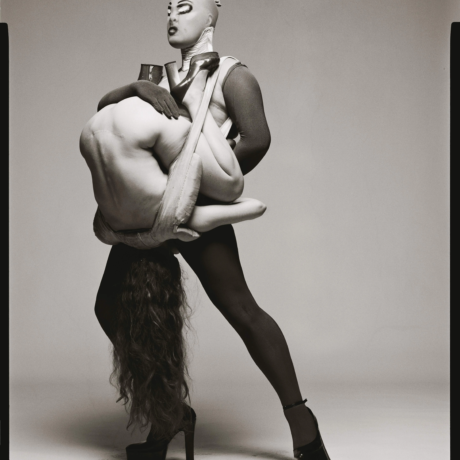

The movements captured on canvases and alluded to on the floor at the Shanghai museum echo back to New York last year where Basco undulated her white-pigment-covered body on a Marley-blue canvas in response to Etel Adnan’s poem, “To Be in a Time of War.”

Adnan’s poem, written from her home in America in response to the Iraq war, captured the Lebanon-born-and-raised artist’s response to a grief and terror so painful, so burgeoning, that even across the world, it seeps into monotonous everyday routines. Written in the infinitive-tense, in a sort of limbo between action and passivity, the poem begins, “to say nothing, do nothing, mark time, to bend, to straighten up, to blame oneself, to stand, to go toward the window.”

Basco first encountered the poem three years ago through her collaborator, the artist Sophia Al Maria. However, it wasn’t until last year when Al Maria left her voice notes reciting the poem that she decided to incorporate the words into her practice. “It really struck me,” she remembers. “The physicality of the poem through voice immediately moved through me. I felt like it needed to be in motion,” she says.

Performing to Adnan’s words was nerve wracking, a first for an artist whose second home is the stage. “It felt like a great responsibility to deal with something like war. I’ve never yet lived directly in war. I’ve never been immediately impacted by it, but I have friends who have,” Basco says. “To abstract something like war from a place that I’m not from, it requires a great amount of respect.”

“It’s such a conflicting thing to be a human. Right now, a lot of the illusions of capitalism are starting to dissolve. Covid was a really big wake up call,” says Basco. “I’m trying to process a lot of the complexities of being alive. And that poem did that eloquently, but without losing the violence and the terror and the paralysing experience of not being able to do anything about it.”

Adnan once said in an interview that “there are many languages which are not made of words. Language is a means of expression, and everything can be an expression.” Basco’s language is fluid, constantly in motion; it finds many forms in her practice. Her vocabulary materialises in body movements and brush strokes. Art’s possibility for human connection has been a throughline in her multidisciplinary practice: it was what brought her onstage over a decade ago in San Francisco when she was fleshing out her performance persona as boychild, and it is what animates her frenetic paintings and drawings today.

Basco first experimented with drawing as a child, but it wasn’t until her father, a photographer, gave her a camera that she discovered her first creative outlet, a language that would both complicate and deepen her worldview. “In the beginning, I used to photograph myself a lot with a 35 millimetre camera,” she says, looking back on her childhood in suburban California. “I didn’t see anyone who looked like me, and I think I became quite fascinated by self-portraiture because I didn’t see myself anywhere. It was almost an inquiry of like, if I exist in image. I really was looking for myself and I found it through self-portraiture.”

Soon, at 19 years old, she was reading Susan Sontag and Roland Barthes and beginning to think about the violence of capturing an image. It caused the artist to pause. “I was like, I can’t do that, I can’t deal with this,” she says. And then I discovered performance.” Performance liberated Basco from the imposed violation of the photograph, which Sontag, in her seminal text “On Photography,” outlined as a device that “turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed,” a subliminal and “soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.”

Through transposing her vision to the stage, Basco reckoned with her deep desire to capture and photography’s violent history. When she discovered performance art, she found a new framework to think about the act of looking. “It allowed me to reflect back on the ways I performed for the camera, and it relinquished me from this compulsion and very deep desire to capture,” she says.

On the stage, Basco began to understand identity as malleable. “The way that I conceive of performance, through drag initially and through my experience as a trans person of colour, is not on a performative stage or theatrical stage,” she explains. Rather, she sees performance in everyday life. “I am learning how to perform myself or un-perform identities that I was subjected to, that were put on to me, or that maybe I do identify as.”

The artist is invested in breaking down rigid notions of identity, both in the macro and micro, the national and individual. She has been exploring ways to “offer porousness to things in the world that might seem fixed,” she says, noting how many ways which we understand ourselves in relation to the world are constructs. National borders are both real and not real in ways that have horrendous implications, she posits.

Today, showing work in China as a Filipino-American is an exercise to think through context for Basco: she sees the two world powers’ similarities mirrored in their differences. “China has a really long tradition of empire, far longer than the United States,” she says, “and they enforce it culturally in ways that enunciate how much it’s enforced in the United States.” She pauses, as if rolling her thoughts around until they form something concrete: “I really try to think about where spatially, architecturally, historically, the work is being shown,” she offers. “It’s a kind of work toward generosity, and it’s quite difficult to do that. I don’t know if it’s successful or not.”

As Basco continues to expand her practice across mediums, memories and motions, her ethos of care and studied intentions creates a grounding force.

Words by Meka Boyle