This interview was first published in Elephant Issue 33

When did you move from Nigeria to the US? What was your life like there and what struck you about the US when you relocated?

I came to the US when I was five, in 1990. I was enamoured by America, my imagination exacerbated by films from this magical place. The moment I arrived, my lack of understanding of this country became glaringly apparent. I didn’t speak English well and struggled early on in school. When I finally conquered the language, it came at a price: I lost my native Yoruba tongue and in so doing severed a personal link to my homeland. From that moment, I moved through the world as if I was trespassing, never certain of my place and always feeling as if I was an imposter.

We lived in the Bay Area of California for the first five years I was here, then moved to Alabama when my father got an associate professorship at a HBCU. That transition from a multinational locale to a segregated one was traumatic. I had to relearn how to adjust to this form of precariousness—with an additive: my being a Black person in a Southern town.

“I moved through the world as if I was trespassing, never certain of my place and always feeling as if I was an imposter”

How did that experience affect you?

The experience shaped me in a way no other locale would have; I became more adept in detecting the shades of my otherness in various spaces—more privy to the subtleties of privilege and prejudice as well as language. This helped me become more acutely aware of the implications of selfhood and how context defines and shifts one’s sense of purpose and belonging. I desperately needed to understand what this meant and how best to articulate it for myself, to be more informed and prepared for what was now my life. I wasn’t a natural writer and miscalculations were a constant. However, in the realm of the visual I found a home, and that has been my way of understanding the world onward.

You’ve spoken of the gap between image and meaning. Do you think about the viewer’s interaction with your work?

I place great emphasis on the potential of viewership and how it can partake in the creating of an artwork. The viewer holds more power than one realizes. You can read the work in whatever way you wish and that doesn’t take away from the artist’s intention—it expands it. I don’t mind ambiguity in my work, but I like to utilize some kind of framework. It’s a push and pull; I like to leave enough room for the viewer to allow their own imagination to take a hold and become a part of the story of the work.

“I place great emphasis on the potential of viewership and how it can partake in the creating of an artwork”

Can you tell me more about these characters who appear in the works at the Whitney?

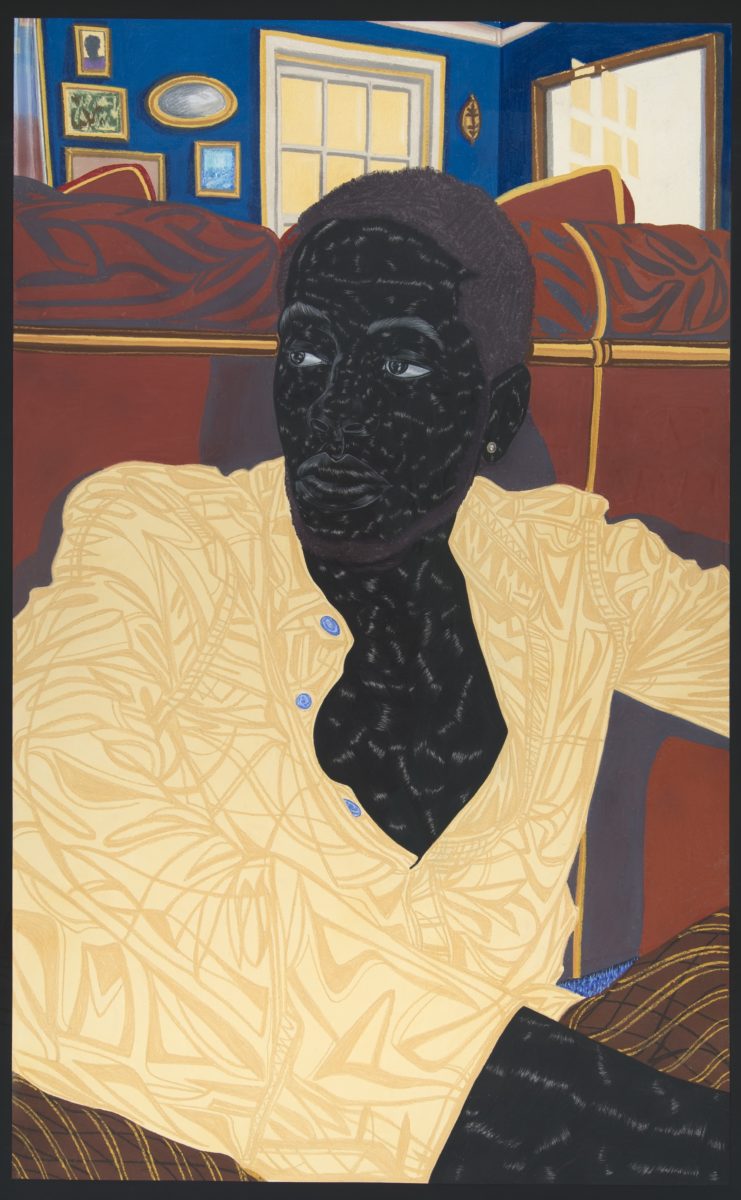

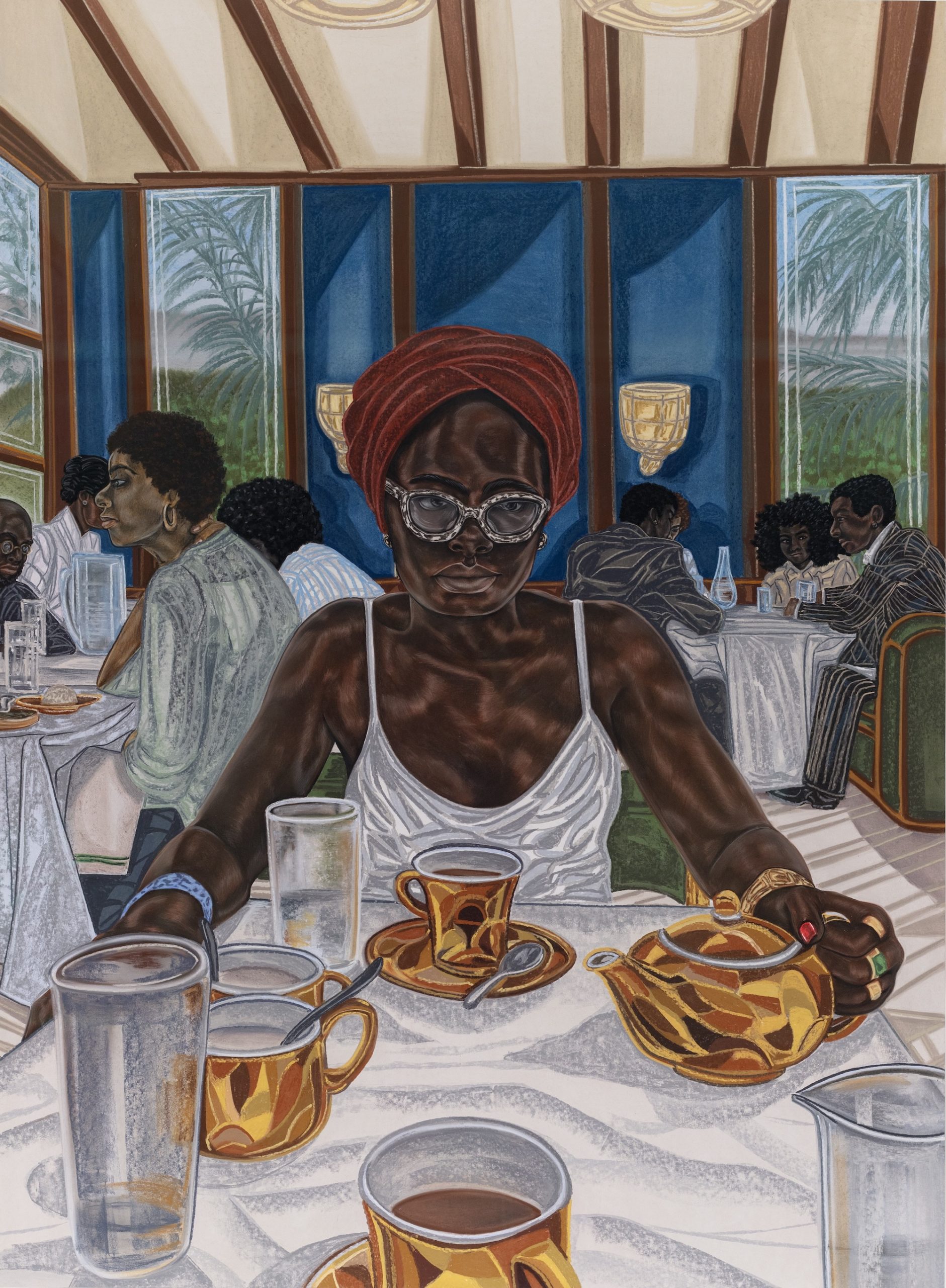

The exhibition is the coupling of two chapters centred around a fictionalized husband duo and their respective families. The first chapter, A Matter of Fact, was exhibited at the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco last year into this spring. It captures the interwoven lives of the UmuEze Amara Clan, with their present Marquess, Jideofor Emeka, at the helm.

It was the beginnings of my exploration into how wealth is depicted when historically oppressed subjects are not only in ownership of their bodies and their selfhood, but also their capital and surroundings. In that first chapter, the questions expanded to how wealth and status affect the way people present themselves in the spaces they create—and demarcate those who are in those spaces. How does one read a portrayal of a subject who is unquestioned?

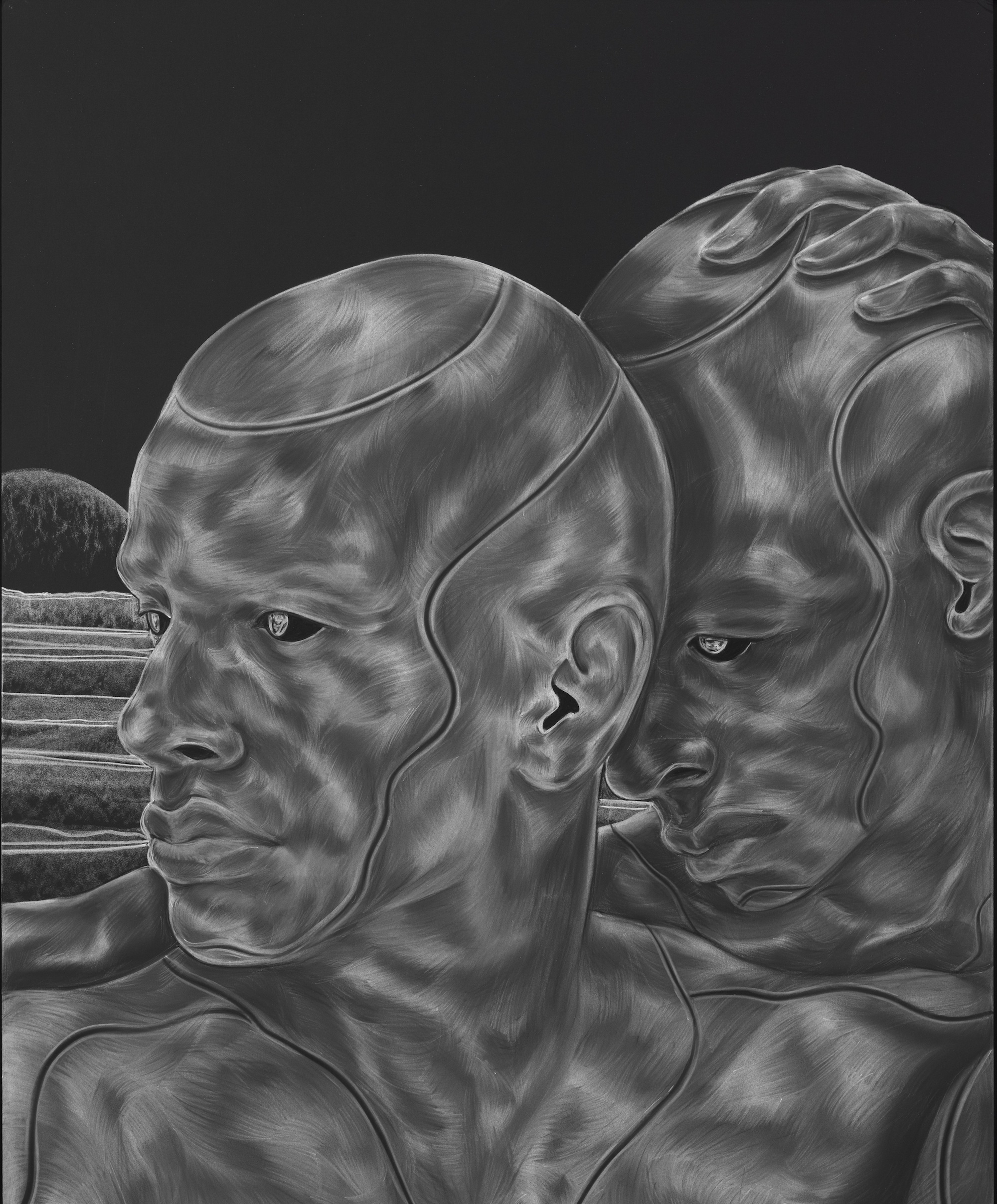

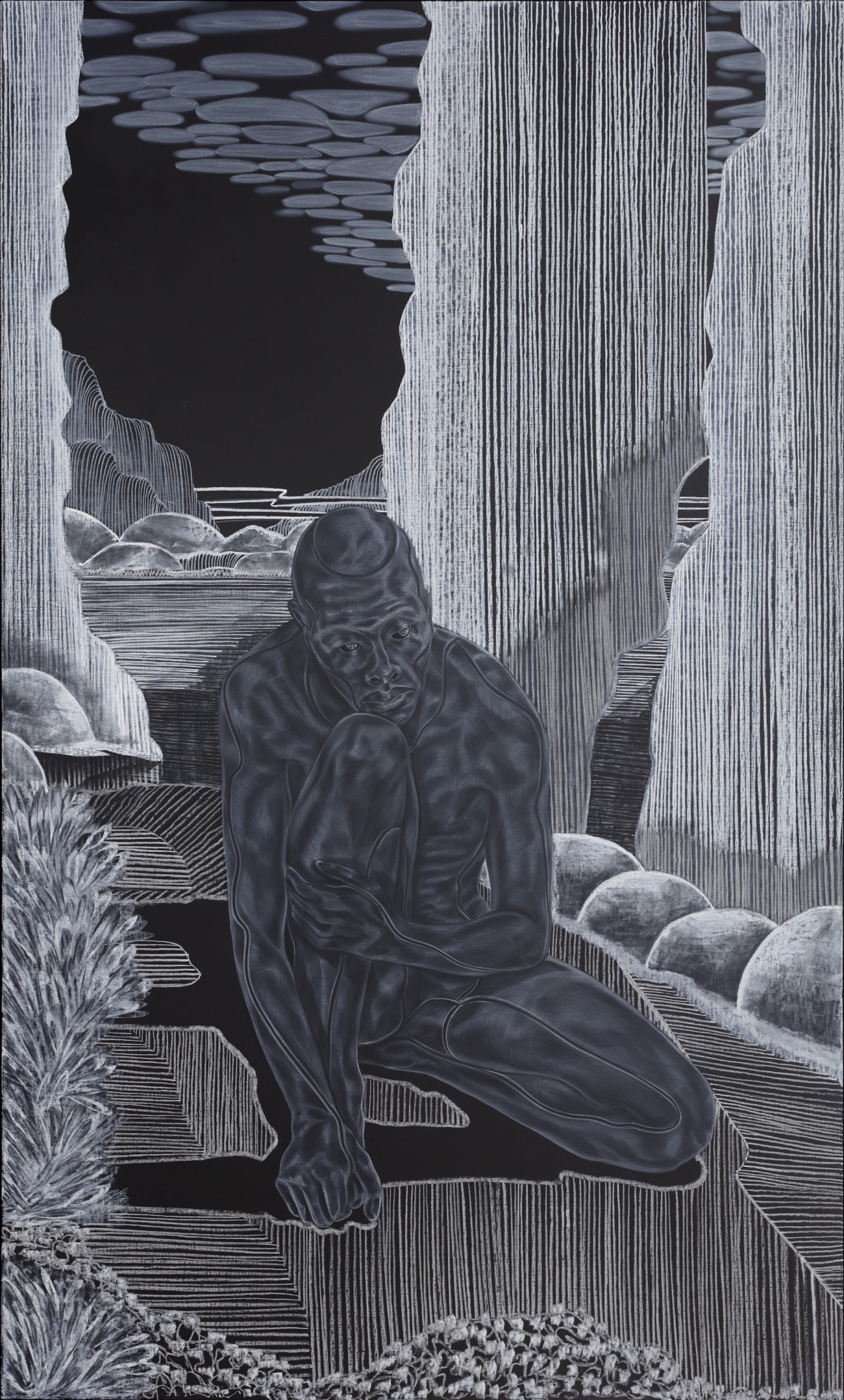

Following that is the second chapter, Testing the Name, which captures the interlocking narratives of the Marquess’ husband, Temitope Omodele, and his family under the baronship, House of Obafemi. This subsequent investigation deals with how wealth affords travel and the luxury of choice in regard to travel. What happens when you depict historically oppressed figures who are in control of where their bodies go? And instead of their bodies travelling, what if we shift the narratives to their selfhood as a mode of travel—their impetuses, interests, desires? What might that look like? That was my aim to discover in the making of this sequel. Their lordships, Jide and Tope, are an extension of my thought process and are the anchors.

Where did the title for the show come from?

Not too long ago, I came across this quote by the author Edwidge Danticat: “The immigrant artist shares with all other artists the desire to interpret and possibly remake his or her own world.” It floored me. Through further research, I found the crux of her argument: that the life of an immigrant, the lands, cultures, principles and beliefs we traverse, is a methodology, a form of art making. Never had my life as an artist been articulated so beautifully and precisely before.

“The life of an immigrant, the lands, cultures, principles and beliefs we traverse, is a methodology, a form of art making”

Being a migrant, in fact and mind, renders everything I do. When your life is defined by precariousness, you tend to downplay your efforts: you try to make yourself small; you speak as plainly as possible to hide inconsistencies; you don’t want to disturb the balance of things because you aren’t really supposed to be here. As the works started coming together, I realized what this exhibition could be on a macrocosmic level: a public showing of my state of making; how it has developed up to this point; and how my own personal narrative as a migrant informs so much of how I think of and see the work. The only words that spoke to me in this regard were “to wander, determined”.

That’s what I have always done creatively: I go blindly forward with an inquiry—not at all concerned with the answer or the outcome, but with the lands, states and spaces I travel through in the process of making. That is who I am as an artist—not simply a Nigerian American woman. I am what I am in this creative field partly because of that three-tiered, conscious fact, not despite it.

This article first appeared in Elephant Issue 33 in Winter 2017

BUY NOW