Tracing the lines of painstakingly printed Indian fabrics is both fascinating and perplexing. What seems to be a perfect pattern can, upon closer examination, be filled with minuscule discrepancies. These characteristic variations denote the technique of block printing, a craft that is enjoying renewed popularity as a viable alternative to garments that feature machine-generated patterns.

Witnessing the process is mesmerising. After the design is inscribed onto a block of wood (usually sycamore or teak) using a pencil, it is gently carved into the surface by hand. Pigments are prepared separately and mixed with glue to ensure fixity, and once the woodblock has been prepared, it is dipped into the ink and carefully, yet firmly, pressed onto the fabric. The artisans then repeat this process, making certain that each print lines up with its sibling, until the piece of material is covered, and the motifs seem to tessellate effortlessly across the textile.

While some claim that woodblock printing originated in China, others cite the Indus Valley civilisation (dating from 3300 to 1300BCE and covering the northwestern part of South Asia) as the earliest pioneers of this technique. Proof of Indian-originated block prints has been found in Fustat, Egypt, dating back to the ninth century BCE. These seemingly innocuous pieces of fabric show that this method was transformed by Indians, who utilised specialist combinations of mordants (chemical agents that fix dye onto fabric) and resists (materials such as wax which are applied to areas of cloth to prevent colour from transferring).

In terms of pattern, the Mughal empire was responsible for an increase in abstract, floral motifs as opposed to faithful depictions of animals or humans. The subcontinent confounded the rest of the world with its ability to produce a visual infinity of colourful pattern. While the combinations were endless, the differing designs in fact functioned as a map of the place from where they hailed. For example, Rajasthan is known for prints of animals and deities. The city of Bagru is best known for its unique Dabu print, an ancient mud-resist technique which is inspired by natural forms.

“What seems to be a perfect pattern can, upon closer examination, be filled with minuscule discrepancies”

Barmer, another Rajasthani city, features chillis and trees as its signature pattern. In neighbouring Gujarat, a type of double-sided printing named Ajrakh proliferates, which originated in Sindh (now in Pakistan). Of Islamic tradition, this complex amalgamation of geometric and floral patterns makes use of classic indigo and madder hues, and often adorns the clothes of cattle herders in the area.

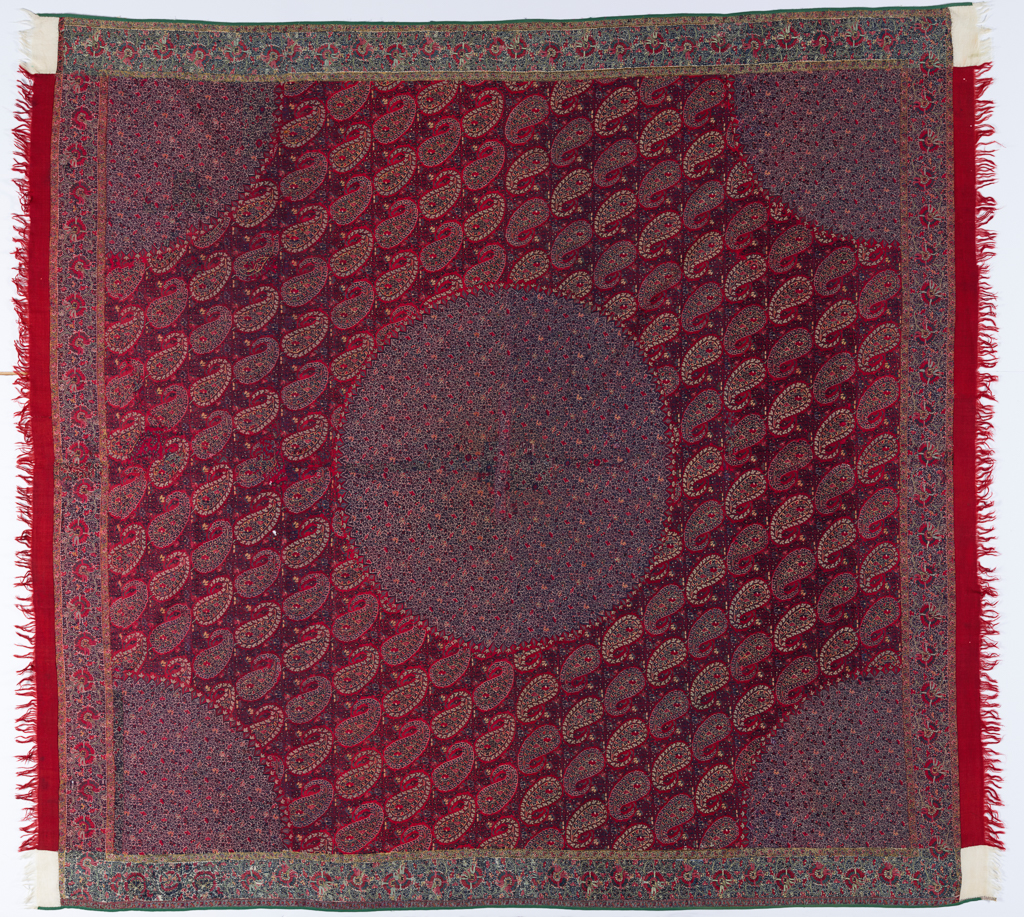

Many of the patterns that are now considered classically British originated in South Asia and were imported by the East India Company. Paisley, in particular, enjoyed quite a journey from its Persian origins to the eponymous Scottish town. The teardrop shape was originally named ‘buta’ or ‘boteh’, meaning ‘flower bud’ or ‘spray of leaves’, and is thought to have derived from the fusion of floral motifs with a cypress tree—the Zoroastrian symbol of eternity.

Courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, RI

The design travelled to Europe in the eighteenth century and its spiritual connotations instantly charmed those on the continent. Imitations proliferated in the town of Paisley, Scotland, resulting in the pattern’s contemporary moniker. The design was adopted by William Morris, becoming an integral part of the Arts and Crafts movement, and evolved from those bohemian roots into the Eastern-obsessed countercultural aesthetic of the 1960s.

“Colonialism acted not only as a facilitator for cultural appropriation, but economic decimation”

Western hunger for ‘exotic’ fabrics is not limited to paisley—it was also characterised by the Victorian ‘chintz craze’. While the seventeenth century

had seen chintz (derived from the printed kalamkari of the Coromandel coast) imported from India, by the mid-1800s production was rampant within Europe itself—appropriation of the design, combined with cruel colonial policy, led to a severe drop in sales for the Indian market, forcing craftsmen to buy poor imitations of their own work. Colonialism acted not only as a facilitator for cultural appropriation, but economic decimation.

Today, block printing is seeing a resurgence through companies such as Anokhi. The business builds ethical relationships with craftspeople from its base in Jaipur, Rajasthan, and commits itself to “providing them with sustained work”. Alongside this, Anokhi showcases the craft’s complexity via a museum in the shadow of the Amber Fort, which spotlights the work of printers such as Suraj Titanwala, who is dedicated to keeping indigenous Bagru prints alive. The sustainable, handcrafted elements of block printing chime perfectly with millennial demand for clothing that does good for the world—let’s hope renewed interest will keep this ancient technique alive.

Anoushka Khandwala is a designer, writer and educator. She currently teaches at Central Saint Martins in London.

This article originally appeared in Elephant issue 45

BUY NOW