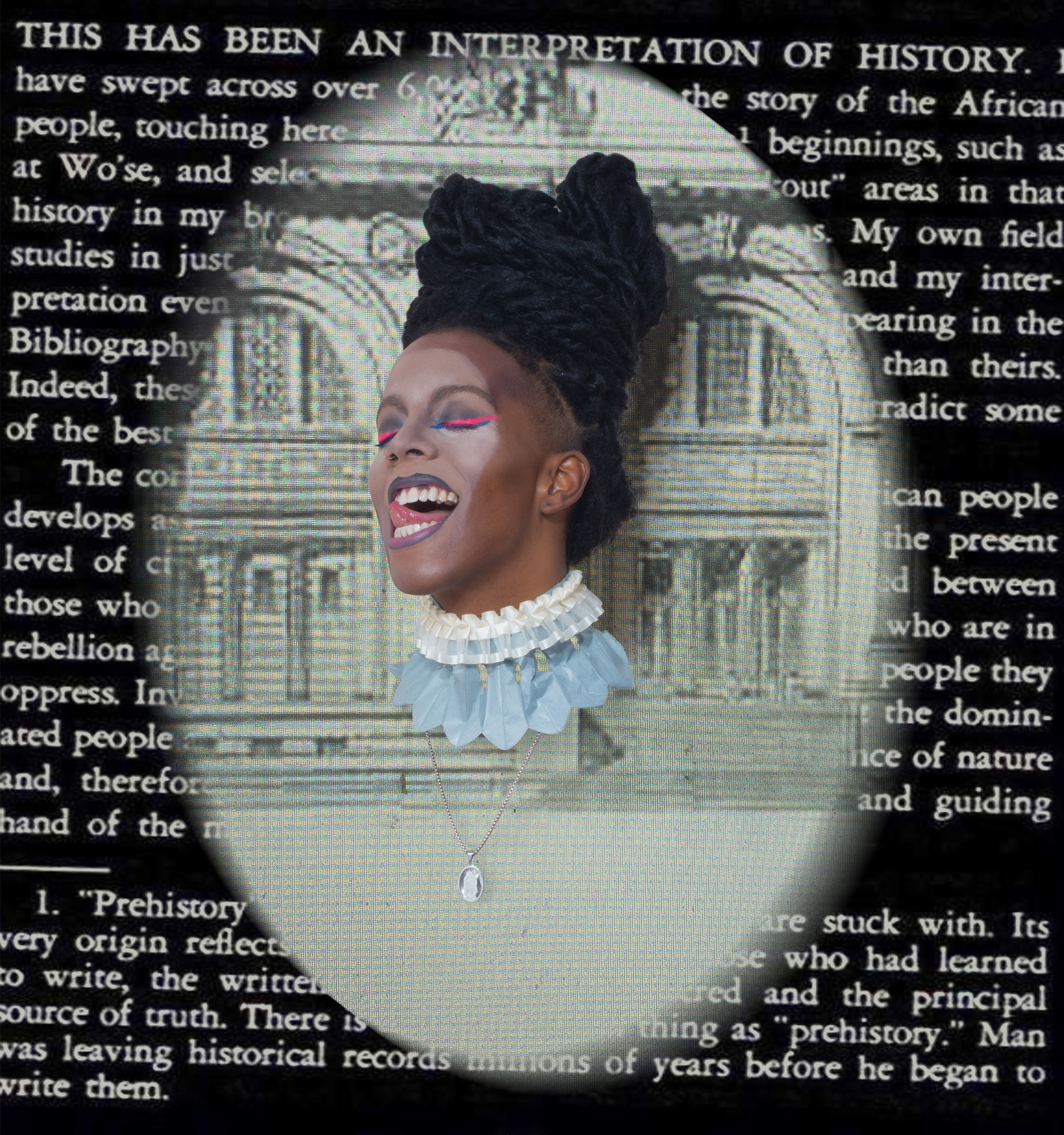

Juliana Huxtable’s performance There are Certain Facts that Cannot be Disputed is obsessed with inheritances, lost genealogies, hand-me-downs, traditions, and alternative delineations of selfhood. Originally co-commissioned in 2015 by MoMA in Manhattan, There are Certain Facts is a cacophonous and sensorial hour-long trip through history, one with dizzying electronica as a backdrop and Huxtable in candy-cute 18thcentury bloomers singing incantatory phrases into a microphone.

Realised through a musical score designed by Elysia Crampton, the eclectic performance combines video, performance and text as the American artist tackles the porous slippages between the self, the past and the digital, and how history is a kind of cosplay.

British writer Juliet Jacques’ Variations (Influx Press, 2021) is a collection of 11 stories that reveals a complex, lonely and joyful slice of trans and non-binary history, which operate in a similar archival and archaeological genre as There are Certain Facts. Jacques’ stories span Oscar Wilde’s London to underground queer activist scenes in Manchester under Thatcher.

On the one hand, Variations is a familiar and cataclysmic set of stories where bodies rub against the law, or against the pathologising, colonial, misogynistic medicalisation of trans bodies at the turn of the century, and the ways in which such regulatory and codifying structures of violence are inherited and re-inherited in the present day.

On the other hand, Variations is also about the small, quiet materialities of queer, trans and non-binary life. The stories are about pleasure, the ‘glorious moment’ of having a corset cinched tight, of sweat and listening to and discovering music, dining and drinking in peace.

Over the last couple of decades, museums, such as the V&A and the British Museum in London, have suddenly begun unearthing previously unseen archival gems, exhibiting a hungry archival impulse to make unheard queer stories known. The Tower of London’s LGBT+ Royal Histories, for example, declares, “LGBT+ histories can be found in the stories of all our palaces”. On a more localised level, there is a plethora of Instagram accounts, such as the extraordinary @transmemory, @lesbian_herstory and @queerloveinhistory dedicated to revealing parts of history that have been reduced to the margins.

“A collection of 11 stories that reveals a complex, lonely and joyful slice of trans and non-binary history”

There has also been a boom in the fictionalisation of characters from the annals of history, where artists, writers and filmmakers are not only making visible previously unknown queer stories, but claiming historical figures and moments as their own. There is queer historical fiction such as Jordy Rosenberg’s Confessions of the Fox or The Confessions of Frannie Langton by Sara Collins, or histories of untold queer life like Hugh Ryan’s When Brooklyn was Queer, or TV series including Gentleman Jack and Ratched, and films such as The Favourite and Portrait of a Lady on Fire.

This impulse to revisit and reread the past illustrates a clear desire to make visible those who have been here all along. Yet both Huxtable and Jacques approach the dynamics of more official archives with scepticism, and the radical possibilities of such spaces for collective memory, visibility, and intergenerational care.

During MOURNING, the second act of There are Certain Facts, Huxtable seems to suggest the internet is as unstable as any archive or historical textbook. In a scene that transposes the erotics of desire onto the erotics of knowledge, with the now obsolete web hosting service Geocities becoming a lost lover-cum-ghosting fuckboy; “Hi Geo, it’s me again”, “Hi Geo, it’s me again”, “In your silence, I’ve begun to wonder, why couldn’t I disappear with you to wherever discarded information goes […] hi Geo, it’s me again, I really just want my text. I DON’T GET WHY YOU WON’T GIVE THEM TO ME […] You were there for me, you offered me storage.”

“Variations is also about the small, quiet materialities of queer, trans and non-binary life”

Huxtable pleads with her lost digital lover to have her texts returned, her things back, but she is responded to with a deafening silence: sometimes history can be so selfish. These moments make apparent the difficulty of mining a history for oneself, of the affective desperation of trying to create, save, recover and value queer artefacts, to memorialise a space that was crucial to one’s queer becoming.

Yet, in lines like, “why couldn’t I disappear with you”, Huxtable seems to question the trap of trans visibility too. Variations asks similar questions: how do we re-read the past in a way that reveals the capacious, joyous, abundant shallows of trans life? And how do we revisit and reveal these lives without making concrete the violence that happened there? What are the pitfalls of such visibility?

The potential for violence lurks around every corner in Variations. In ‘Standards of Care’, Sandy is far too visible in her hometown of Norwich: after a boot is thrown at her head, she reveals, “it’s hard to stay hidden in a city this small but plastering myself in lippy and throwing a little clutch bag over my big shoulders ain’t going to cut it.” The dangerous trap of visibility is hard felt in stories such as this, yet Jacques also elides such causal moments of visibility and violence through a politics of representational refusal.

Many of the stories here don’t only take place in the narrative structure of the story itself. There are interviews discussing performances that took place in a nightclub somewhere at some point; film scripts that feel like they have and haven’t taken place, or might lie in the drawer of a well-meaning director somewhere; and transcriptions of gestures and descriptions of moments where bodies were once live and vivacious.

Jacques delicately captures an ephemeral network of occasions when trans and non-binary people have been hailed in public, when they have been visual, visible, consumed, both violently, as a spectacle, but also in private, in soft, pleasurable moments of intimacy, in sex and in love. Jacques’ rendering of these bodies, once performing, once known, but now off-stage, beyond our gaze, offers the reader a more concealed mode of trans visibility.

“How do we re-read the past in a way that reveals the capacious, joyous, abundant shallows of trans life?”

I sometimes felt like the characters were always slightly out of grasp—formally and narratively—I didn’t have full access to their interiorities. Like a hall of mirrors, they glimmered, multiple, always at a remove, whether because of their formal rendering (it’s infinitely more difficult to fully know someone through another’s description of them dancing on stage) or because Jacques manages to paint characters in control of their own images, where we as the reader can’t so readily consume them.

We might argue that Variations is tonally blurry, and it is in these moments that it offers a visionary and expansive politics of refusal. Reading it is less like reading a book, more like experiencing an object, turning it over and around, discovering its unseen underside. It reminded me of Chris Vargas’ Museum of Trans History and Art (MOTHA), which I encountered at Oakland’s Museum of California in 2019.

“We might argue that Variations is tonally blurry, and it is in these moments that it offers a visionary and expansive politics of refusal”

The radical conceptual art project, together with its travelling exhibition Trans Hirstory in 99 Objects, aims to “ask audiences to think critically about what a visual history of transgender life could and should look like, and if it’s even possible to compile a comprehensive history of an identity category for which the language is fairly new.” From blurry candid polaroid photos and sequinned jackets worn by Sylvester, the celebrated ‘Queen of Disco’ to the stiletto heels of the indomitable trans prison abolitionist Miss Major, the project feels like a self-proliferating, expansive, decentred notion of the archive, one where you’re never quite sure whether it is fact or fiction.

As with MOTHA, it is sometimes hard to know what is real and what is not in Variations, what is historical and what is fiction. For a while, I read the book in tandem with Googling the different figures and moments, trying to ascertain a version of the truth, but quickly realised Jacques wants us to exist in this sticky place between the known and the unknowable.

In doing so, Variations provides a radical commentary on the demands of visibility, and the imaginative possibilities of those who refuse to be knowable or to be completely hailed by history.