In 1927, the German physicist Werner Heisenberg presented his Uncertainty Principle, which states that the more precisely the position of an object is known, the less precisely its momentum can be known, and vice versa. The principle demonstrates how, on the most elemental level, the total “truth” of an object cannot be definitively known. The Uncertainty Principle, a vital discovery in quantum mechanics contradicts the way many humans have understood the universe for hundreds of years; instead of a world of absolutes just waiting to be measured or defined, Heisenberg revealed that uncertainty is a fundamental characteristic of our universe.

“In today’s Information Age, deterministic binary opposition appears to have fully saturated Western society.”

Western society, often holding the belief in an eternally definite stasis of humanity, has a long tradition of insisting on binary distinctions (woman/man, white person/person of color, real/virtual, straight/queer, valuable/not valuable, pure/impure, presence/absence). Though its origins go as far back as Plato trying to reconcile his idea of the physical world and the eternal world of ideal forms, this bias began to take root during the Scientific Revolution and was further energized by the Industrial Revolution and twentieth-century capitalism. In today’s Information Age, deterministic binary opposition appears to have fully saturated Western society. Developments in quantum computing, however, reintroduce the notion that the universe relies on uncertainty and probability, thus making absolute binary distinctions irrelevant. Though it may seem ludicrous to imagine a world in which humans experience the idiosyncrasies of particles on an atomic level—a constantly shifting cloud of uncertainties and probabilities—metaphorical parallels offer a feast of opportunities to reconsider the centuries-old model of human identity.

Harry Dodge’s film The Ass and the Lap Dog (Or, Maladie du Pays) (2013), ostensibly the least gender-focused piece in the New Museum’s new exhibition Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon, offers a literal and nuanced examination of logic and certainty. Through a series of vignettes, we meet five people who the artist takes to different mundane locations. Dodge asked each participant to describe how the site reminds them of home, then, after a brief and befuddled examination of their surroundings, they say it doesn’t remind them of home, but it does make them imagine a clear concept of a video they’d like to make. The following narratives unfold like fever dreams, weaving physical impossibilities with philosophical inquiries.

“We must commit to the gradual dismantling of illusions of certainty.”

At first, the film seems to be a series of rambling non-sequiturs. However, after reading Dodge’s description of the piece on his website (which the exhibition label doesn’t mention), the film erupts with complexities. The title comes from a story, written by French fabulist Jean de la Fontaine, in which a dog receives caresses when he rubs against his master, but when an ass repeats the action, he is abused and beaten. Dodge writes that “[the film] focuses on similar problems of transposition, or of flawed translation—of being ill-equipped, untrained, displaced, not ‘passing’—which could also be thought of as a type of homesickness (‘maladie du pays’).” Each of the monologues—which seem like improvisations but are scripts written by Dodge—use incoherence as a vehicle to reconsider what is possible, both physically and socially.

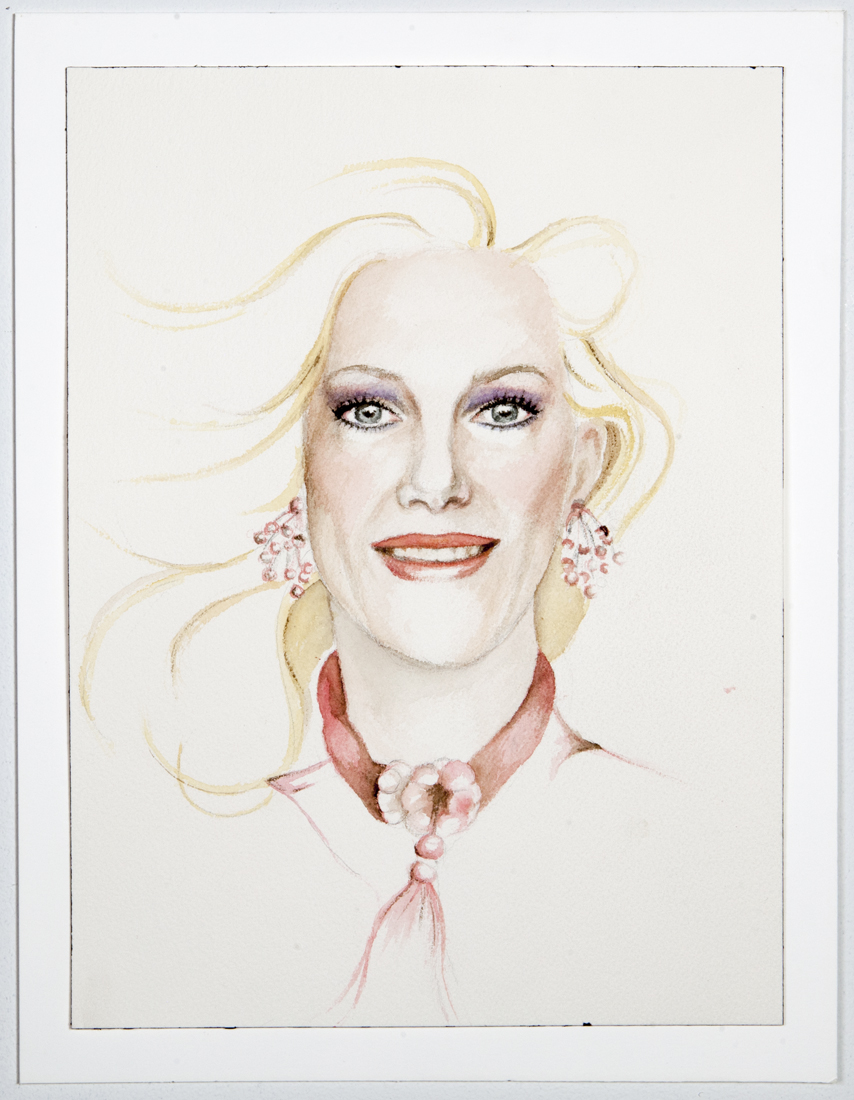

While Dodge’s characters theorize absurd alternate universes, for some of the artists in Trigger, the simple act of existing outside societal norms contradicts the historical logic and standards of their inherited culture. Justin Vivian Bond, Liz Collins and Vaginal Davis represent a generation of artists born into the tumult of Gay Rights gaining ground while conservatives viciously fighting back. Younger generation artists Reina Gossett and Sasha Wortzel pay homage to the groundbreaking work of their predecessors, in particular, to the transgender artist, activist and self-identified drag queen Marsha “Pay it no mind” Johnson. Twenty-five years after her unresolved death, Johnson is still a mythic figure in the LGBTI+ community. Considered by many to have launched “the shot glass that was heard around the world,” Johnson and her friend and fellow activist Sylvia Rae Rivera were among the first to ignite the 1969 Gay Rights Movement. Lost in the Music (2017)—an excerpt from Gossett and Wortzel’s forthcoming short film, Happy Birthday Marsha!—imagines the hours just before the Stonewall Riots began.

In the New Museum, the film plays on one side of a floating wall suspended from the ceiling with a giant shattered mirror on the verso, representing the shot glass thrown by Johnson at the Stonewall Inn. We see actress Mya Taylor as Johnson, walking through an adoring crowd and onto a stage lined with shimmering tinsel. Wearing a hat overflowing with flowers and dangling crystals, Taylor recites Saint’s Poem. Though the performance clearly references Johnson, Gossett and Wortzel made some curious decisions concerning their reconstruction of the moment, producing both an homage to and an idealized memory of Johnson. The dialogue is an almost verbatim copy of a real performance given by Johnson in which she recites her poem Soul, not Saint’s Poem, (written by Grace Dunham for the film). Taylor masterfully captures the emotion of Johnson’s speech, but misses Johnson’s particular accent and slight lisp. Both celebratory and ominous—the excerpt ends with a group of cops entering the bar—Lost in the Music spotlights an important figure in the history of challenging societal gender norms. Marsha P. Johnson was not beholden to the expectations to be a man or a woman—she was only herself.

Tiny quantum objects like electrons can exist in two contradicting states at the same time. Called superposition, this phenomenon is necessary for everything from the formation of chemicals to the production of the silicone used to build the transistors that power the digital device you’re reading this article on. Though we interact with things that express quantum phenomena, we never directly observe them at a human scale. However, by projecting a metaphorical model of quantum mechanics onto social interaction, we can begin to see the ways in which the physical world provides a model for understanding society. If we consider beings like humans to be the tiny quantum objects whose interactions produce effects on the larger societal scale, then the idea of a human existing in two supposedly contradicting states, such as male and female, would be entirely commonplace.

The impracticality of uncertainty should not discourage us from trying to make a change. We can, as Jean Baudrillard wrote, “dream of a culture where everyone bursts into laughter when someone says: this is true, this is real.” We must commit to the gradual dismantling of illusions of certainty. A possible method to achieve the attenuation of our accepted perception of reality is through an emphasis of being, instead of being something.

Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon runs until 21 January at New Museum, New York

newmuseum.org