Given the current state of the world, it might seem crude to write or make art about the phenomenon of celebrity. In many ways, it is, but so is our unceasing fascination with it. Fame is as much about its onlookers as it is about its beneficiaries. The writer John Updike once called celebrity a “mask that eats into the face”. Stardom is inescapable now; it would seem that this proverbial mask has eaten into all of our faces. How can we ever truly understand ourselves when our identities fall between social media-fuelled narcissism and the idolisation of others? Both Philippa Snow, in her illustrated essay Trophy Lives: On the Celebrity as an Art Object (2024), and Ruby Dickson, whose solo show at Nicoletti Contemporary closed last month, aim to decipher the art of celebrity. Whilst Dickson takes the star as her muse, Snow dissects it as a work of art in itself.

Making an art of celebrity doesn’t necessarily discount its vapidity. Art and stardom have always been entangled– the flattery of a 14th-century monarchical portrait is a predecessor to the digitally manipulated ad campaign. So, too, is art history’s adoption of the female body as a muse, which isn’t so ‘historical’ after all. Female celebrities are no less sites of cultural intrigue now as they were ten years ago, in the early-internet paparazzi heyday of the noughties (albeit less mediated by gossip blogs and tabloids). Advertisements and abuse of power are played out in real-time via TikTok and self-branded podcasts.

Snow’s assessment of celebrity as art allows her to analyse it discerningly, in the capacity of an art critic. “Disappointingly sublunary”, Snow writes, “to think that a star might be no more than a product– but then it is equally depressing to think that the same is true of a supposed artwork”. As a form of self-advertisement, celebrity is a devoted task, requiring what the author calls a “saint-like” determination, often extending to self-sacrifice or ‘mutilation’ (plastic surgery). I think of Marina Abramović, whose popularity is so entwined with her persona as an artist; she is the embodiment of art-fame synthesis. Like a celebrity’s, the crux of Abramović’s performance practice is her presentation as a martyr (suffering but stoic) and her self-mythologisation.

Stars also act as cultural markers of their times. In this sense, magazines are the gallery, journalists, and curators– only the PR agents remain the same. The anonymous administrators behind Deux Moi, a popular celebrity gossip mill Instagram account, describe themselves as “curators of popular culture”– this might all sound rather presumptuous, but it isn’t wrong. Snow’s dissection of the fame phenomenon is befitting of our age. Though it might sometimes seem it (think plastic surgery denials and low-res photo-dumps; they’re just like us), it would be naive to assume that the majority of stardom’s upper echelons were unaware of their cultural prowess. Business is business.

The publication of Trophy Lives coincides with the closure of an exhibition at Nicoletti Contemporary in London: Ruby Dickson’s ‘MAYBE MY FAIRY-TALE HAS A DIFFERENT ENDING THAN I DREAMED IT WOULD. BUT THAT’S OK’. Stardom has long been a subject of fascination for many visual artists; something interesting happens when celebrity (a la Snow’s argument, a work of art in itself) is taken as traditional art’s subject. Which is the better work of art: the celebrity or the celebrity as muse?

In 2003, the artist Maurizio Cattelan was commissioned to produce a sculpture of model Stephanie Seymour. Untitled (Stephanie), otherwise known as Trophy Wife, is a life-size, naked vision of Seymour, modelled after the figurehead on a ship’s prow. I’m hesitant to call it a replica, because, as Snow says, it “makes little attempt to accurately mirror the real Stephanie’s countenance”, instead appearing as the kind of creepy mannequin found in a cheap, funfair wax museum. The work was commissioned by Seymour’s husband, Peter Brant, and Cattelan emphasises this, cutting off the body before the sex and turning the figure into a collectable object with no use: a trophy wife.

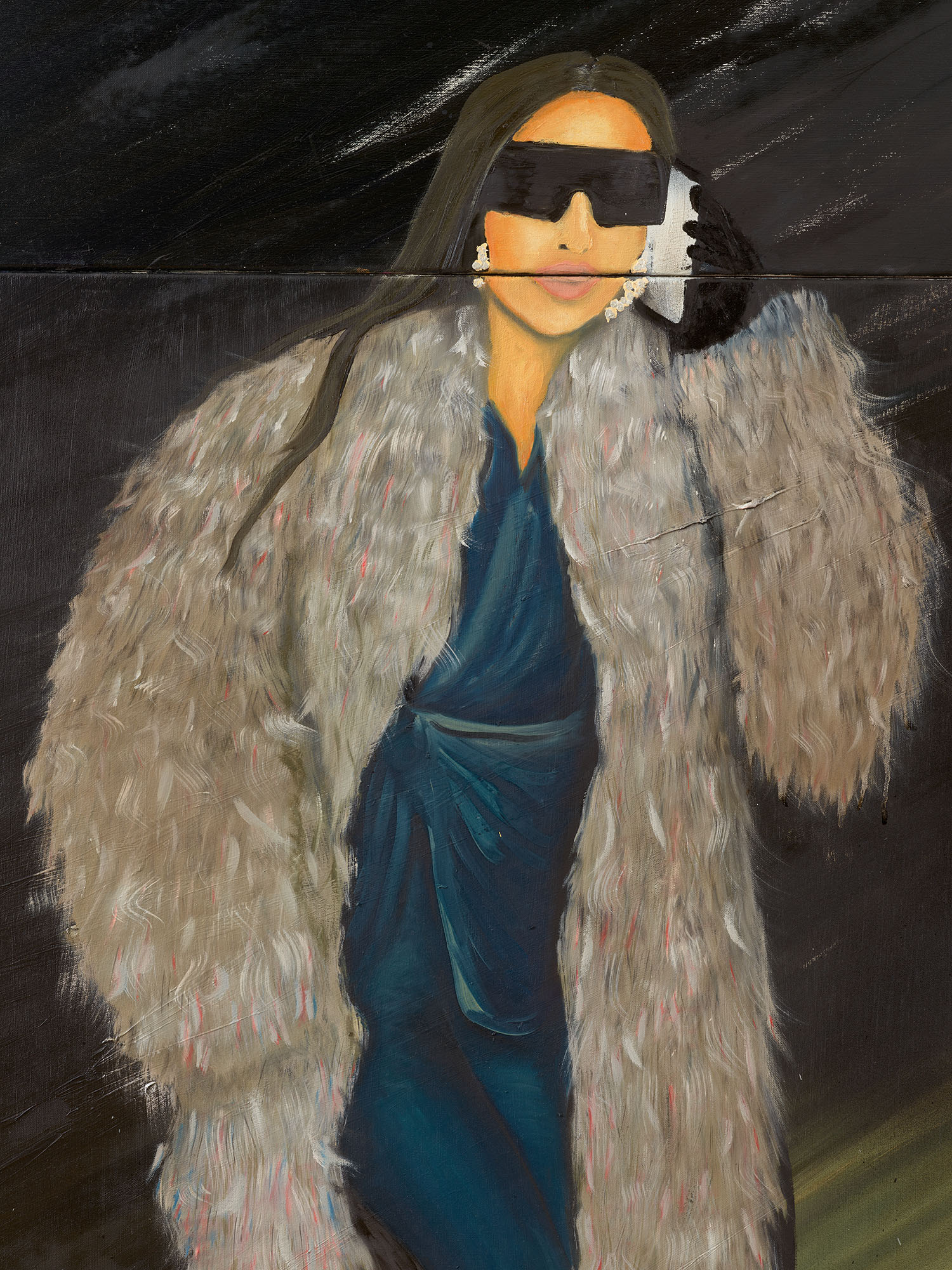

The real debate lies in the difference between Seymour herself, as an ‘icon’, and her doppelgänger, which highlights the two strands of ‘celebrity art’, art about celebrity and art by celebrity. In acknowledging this, Snow argues, “It follows that we could enjoy [celebrities] for exactly what they are: tirelessly constructed and finessed objets d’art, each living in service of his or her own creation by presenting themselves in the best possible light.” Similarly to Cattelan’s disconcerting, waxy rendition of Seymour, Dickson’s paintings of Kim Kardashian are disquieting: whether it is the sense of voyeurism they inspire when hung in a white-walled gallery (as if this is any different to looking at Kardashian on a screen), or the subtle ‘off-ness’ of their subject. Though their scenes are all appropriated from paparazzi photographs, their presentation reminds me of fan art.

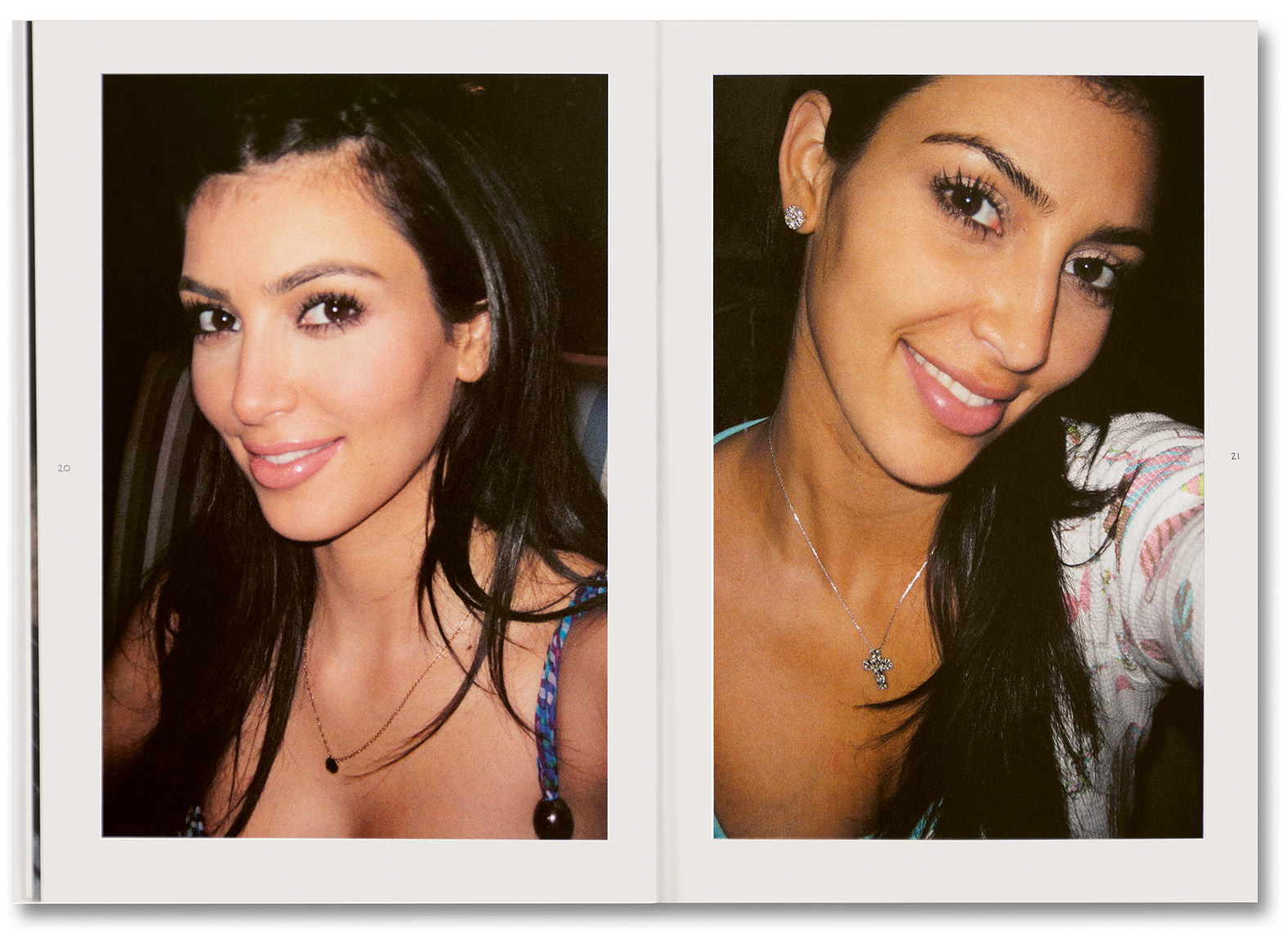

In the words of art critic Jerry Saltz, Kardashian is the ultimate “performer of fame”. Her 2015 Rizzoli publication Selfish is an incarnation of this: a flip book of bodily metamorphosis from Californian princess to sex icon. It is, as Snow describes, “ORLAN-esque, science-fiction-level shapeshift-ing”. Dickson’s Kardashians are similarly shape-shifted, each appearing slightly anonymised and different from the last, with canvases split violently across their faces, manifestations of the separation between mind and body. They also raise questions of the star’s distance from, and proximity to, Blackness– herein lies another similitude to ORLAN, whose mid-90s Self-Hybridisations involved the digital manipulation of her own face to adopt the characteristics of those she described as “non-Western referents”. It’s a claim to post-racialism accommodated by privilege, and whilst Kardashian doesn’t explicitly categorise herself in this way, there is certainly something uncomfortable about the ambiguity of her origins.

Through selling laborious paintings of one of the most publicly accessible figures in the world, Dickson lays bare the mini-economy of celebrity, like the mini-economies of artists, involving gallerists, collectors, the media, and auction houses. Kardashian’s main commodity is her image, which is monetised partly by paparazzi pictures. Dickson downloaded those images– with their exaggerated, narratively suggestive captions– removed their backgrounds (who needs context when you have a Kardashian?), and presented them at art fairs and commercial galleries alike. The artist– with no obvious direct connection to Kardashian– is (presumably) making money off her image, and why shouldn’t she?

Since the circulation of celebrity has never been exclusive, it could be argued that its image power is even more robust than that of traditional forms of art. The nature of fame affects the way we interact with the world, empathise with others, and understand ourselves. In this sense, art and text about celebrities are an urgent addition to cultural criticism.

While traditional art has a gallery, celebrity has never been granted a space in which it can be examined and questioned in a ‘neutral’ manner. Snow writes: “it is interesting that when we describe a person as a ‘work of art’, we do not usually mean that they are worthy of analysis or thought, merely that we like to look at them”. By approaching celebrity as art, we don’t aggrandise it. Instead, we imbue it with meaning, enabling us to see this world– and enjoy it– for what it really is.

Written by Ella Slater