A “documentary fiction” is how Gilles Peress describes his most recent expansive photography project. Chronicling 22 semi-fictional days of The Troubles, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing pulls together images from the thousands of photos Peress took during his stays in Northern Ireland during the 1970s and 1980s.

On show as part of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London, the project’s name will be familiar to many. Seamus Heaney wrote a poem using the phrase as the title, while Patrick Radden Keefe’s book about the era, Say Nothing, became wildly popular. It was also used on an IRA poster, a photo of which appears in Peress’s project

It is a good title for a work relating to The Troubles. It brings to mind certain societal characteristics of the North at that time (and now): secrecy, surveillance and subversion. But the formulation of it I am used to hearing from family and friends, and saying myself, is slightly different.

The one everyone says is “But sure, I’m saying nothing”. People say it when they tell you the gossip (the “biz”), after a story about political corruption or paramilitary activity (it’s mostly about drugs now), or some kind of moral hypocrisy (the North remains a socially conservative place, outwardly at least).

“Time is strange in the North. History is everywhere, painted on buildings and acted out in parades, riots and violence”

“Was I telling you about the 60-year-old man down the street who’s leaving his wife for some woman not even 30?” But sure, I’m saying nothing. “Did you see the PSNI never closed down those lockdown parties on the Shankill?” I am saying nothing. “Did you hear about your man from the DUP, has been seeing some wee lad, paying for hotels on expenses?” But sure, I’m saying nothing.

It can mean a lot of things: “I don’t need to say anything, you know what I think”; “I shouldn’t talk, it’ll get me in trouble”; “He’s making a fool of himself”. The list goes on.

Mostly it’s a joke, about the secrecy, the furtiveness, the history and culture of violence. It’s a type of humour you hear a lot of in the North: weird and dark, and trying to make something entertaining out of our shared, tragic history.

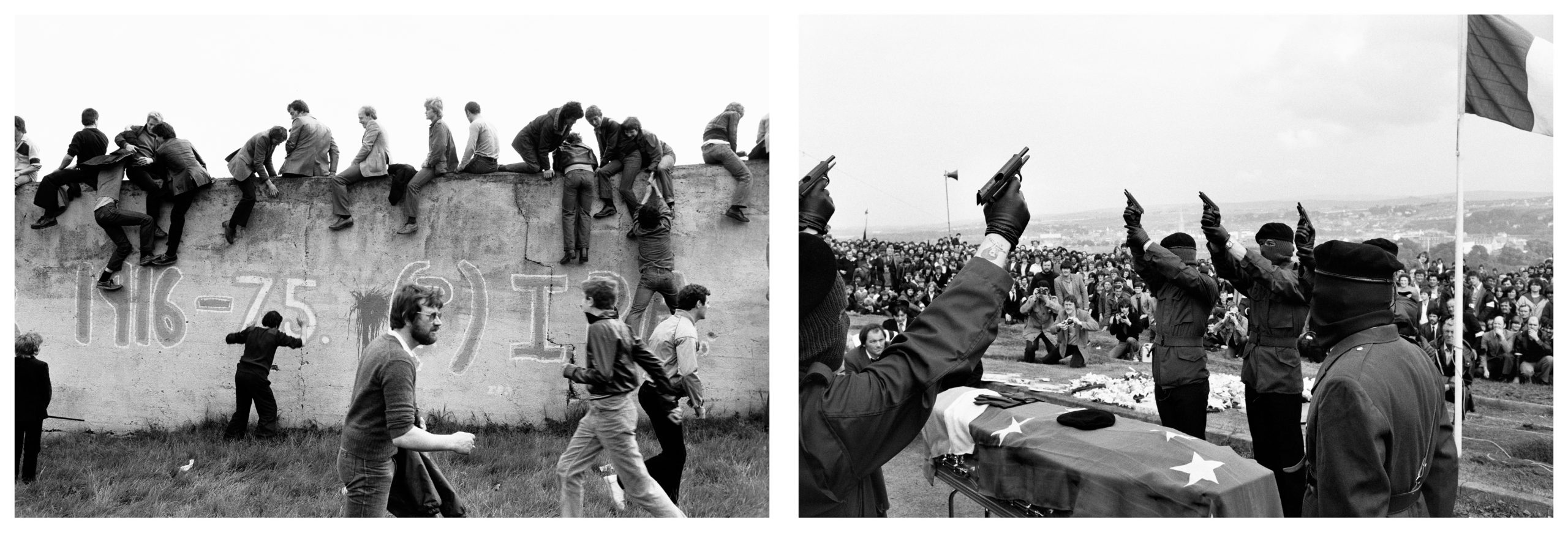

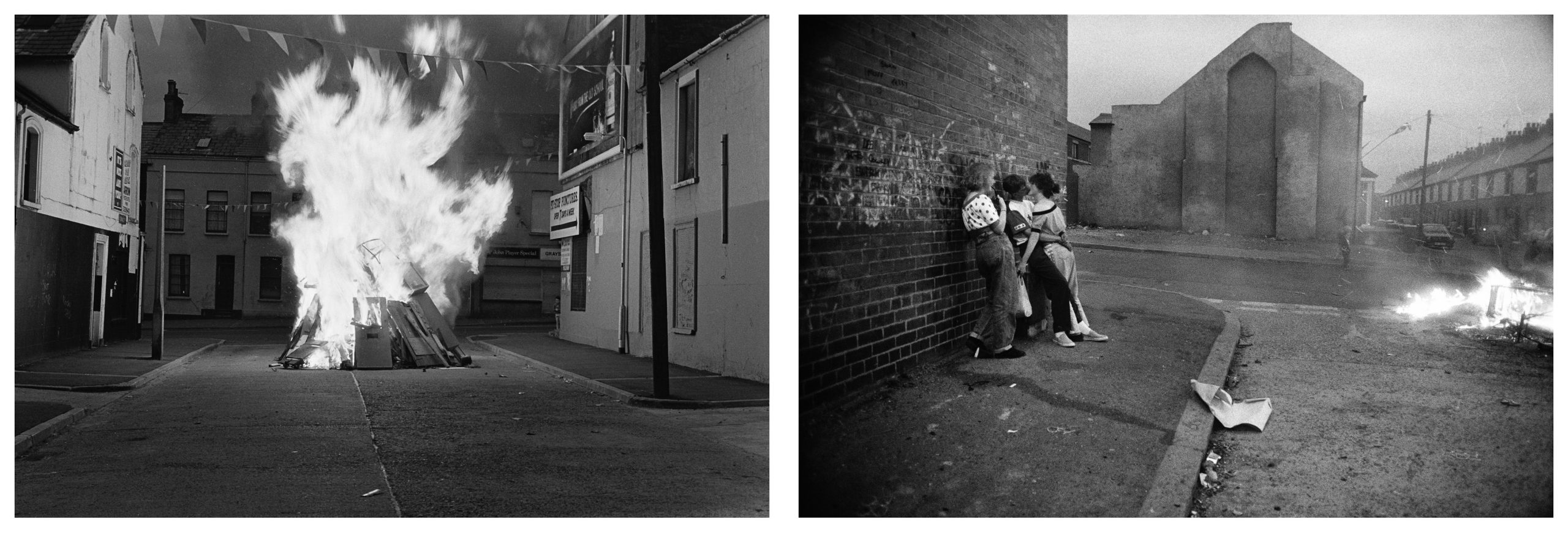

Peress’ photographs show rioting, devastated wastelands and protests over discriminatory policies denying Catholics fair access to housing, work and voting rights. Also depicted are protests against internment, the discriminatory practise of imprisoning Catholics without trial for sometimes very tenuous links to paramilitary activity, often without any real evidence. Despite the devastation also wrecked by Loyalist paramilitaries, Protestants were broadly spared the tactic. (A thorough accounting of this can be found in Making Sense of The Troubles by David McKittrick and David McVea).

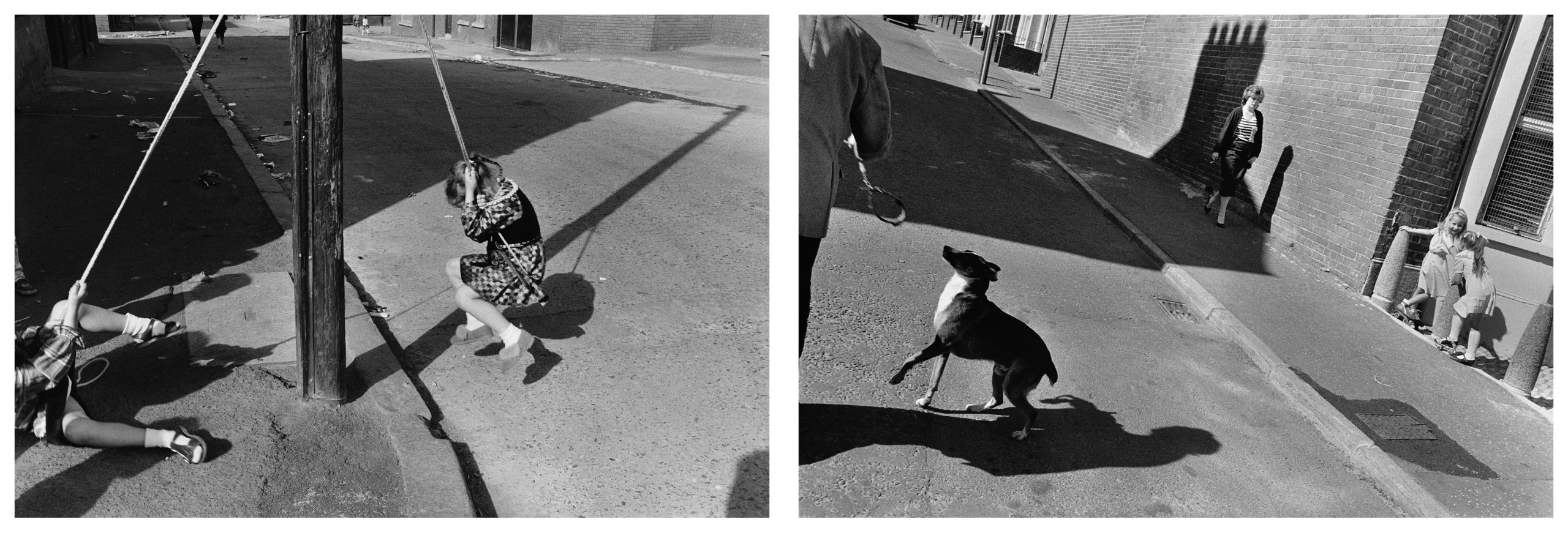

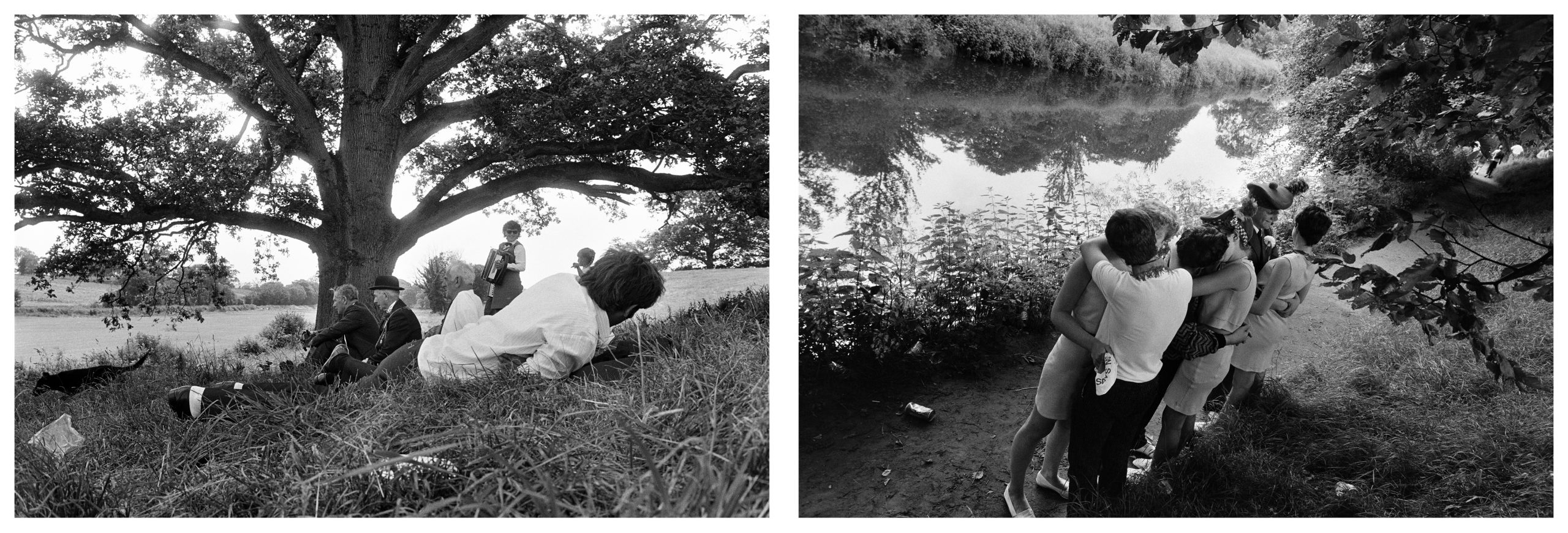

The French photographer also depicts a lighter side: people in fancy dress between bars or parties; the crowning of Miss Belfast at a flower festival; unionists celebrating royal weddings; days out in the countryside. The craic, basically.

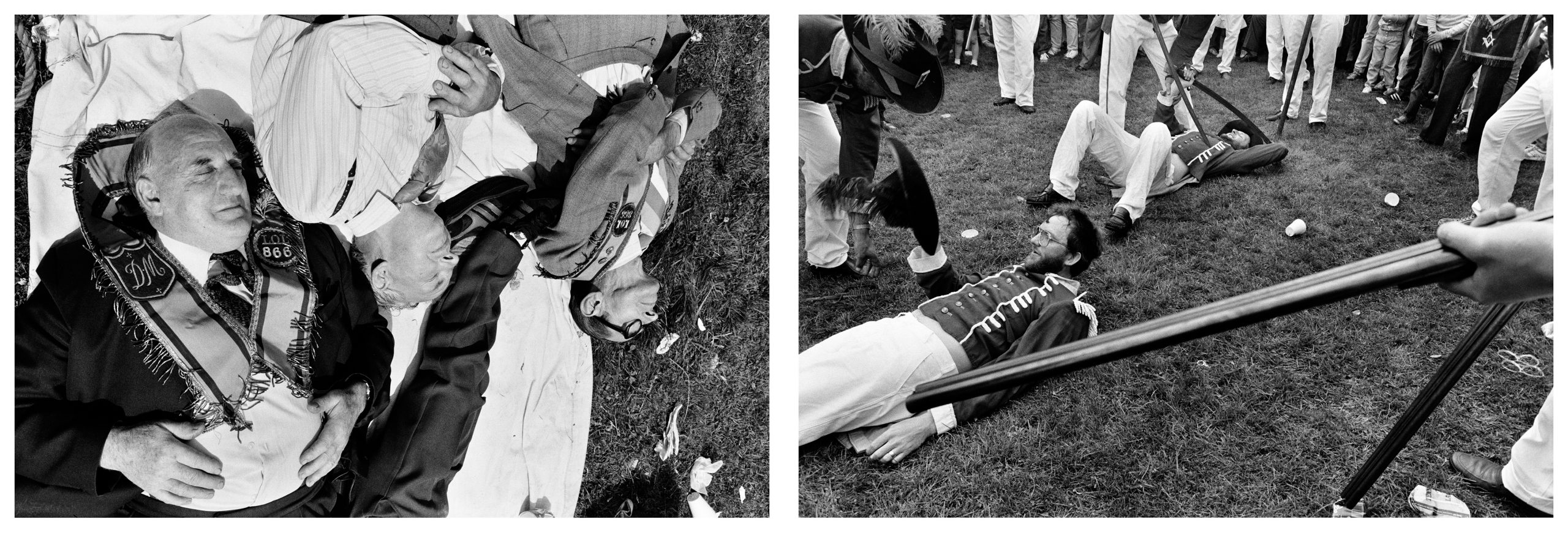

Each semi-fictional day consists of photos from across The Troubles period, grouped thematically to recreate the essence of events. A short, poem-like text accompanies each entry. In one, A Day To Remember, Peress presents a vision of Unionist celebration. “A Protestant day, a Loyalist day, a Unionist day, both rigid and loose,” the text starts. These festivals are controversial in the North. They are, by definition, exclusionary to the Catholic community and are still often the source of riots and arguments due to deliberately provocative behaviour (changing the route to march through Catholic areas, burning images of Catholic politicians on bonfires, and so on.)

“It brings to mind certain societal characteristics of the North: secrecy, surveillance and subversion”

Peress resists narrativising them as such, instead presenting a day of jubilation. Orange Order members in bowler hats and sashes march past middle-aged women dressed in their Sunday best. Young men drink beer and play their drums, and couples kiss by the riverbank. There is laughing, drinking, fun. Tattoos are exposed as tops come off: the familiar Union Jacks beside “No Surrender”s and one “Made in Belfast” scrawled over a belly button with a birthdate tattooed beneath it. It is a humanising portrayal of a facet of our culture which has always seemed impenetrable and hostile to me, and yet these were the photographs I spent the most time with.

Although presented in exhibition form for the Prize exhibition at The Photographers’ Gallery, Whatever You Say, Say Nothing

was originally arranged over three books: two photo albums and then a companion almanac of contextual material, Annals of the North. Here there are descriptions of various characters of The Troubles, politicians and local personalities. One entry in particular made me smile: The Dohertys “A sprawling Catholic clan originally from Donegal… If someone is Catholic and from Derry, his or her granny is likely to be a Doherty.” My Derry grandma is a Doherty.

The almanac also has an innovative timeline, the non-linear form of which communicates something fundamental about temporality in the context of The Troubles. Events are organised by month and date, but not by year. For example, 4 January 1976, when Loyalist paramilitaries shot dead six Catholic Civilians in County Armagh and County Down, is followed by 6 January 1980, when the IRA exploded a land mine, killing three members of the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR).

On 25 March 1993 (the year I was born in Belfast) the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF: a loyalist paramilitary group) shot dead four Catholics, including one IRA member, and later another Catholic teenager. In the almanac this is followed by 28 March 1979, when James Callaghan’s Labour government lost a confidence vote in the Commons, triggering the election which brought Margaret Thatcher to power (with knock-on effects for the treatment of Republican prisoners, and therefore rioting.) Open any page of the almanac and a pattern continues from the 1600s into the 2000s, with events separated by decades or centuries linked in an endless circular web of recriminations.

Time is strange in the North. History is everywhere, painted on buildings and acted out in parades, riots and violence. A history that is largely ignored in England. In England there is a lack of understanding and compassion (let alone sympathy) about what it means to be from Belfast, a post-conflict, sectarian society where PTSD is rife, although nobody calls it that. Beyond that there is a perceptible sense of blame. This presents as straightforward bigotry on the right, or among middle-aged men, with “jokes” about the IRA fairly common. Loyalist paramilitaries like the UDA and the UVF always go unmentioned, of course.

On the left, there is an insidious, cheerfully wilful cluelessness about the reality of The Troubles and life in the aftermath which manifests as demands for explanation, or an accounting for the backwardness of hard-line politicians. And there is the (perhaps subconscious) refusal to acknowledge events in the North as an example of colonial violence, police brutality or a civil rights issue at all, which implicitly accepts the narrative of The Troubles presented by the British state.

English people seem to think of the North as a dark, tragic place, naturally predisposed to violence, about which the less said the better. In reality, it is complicated, fractured and full of tough, resilient, kind people trying to make the best of things. People often jokily say is “Take me out and shoot me.” I love that humour. I see so much warmth in it, so much light in a place outsiders tend to view as bleak and depressing.

This is the real strength of Peress’ project: he can see the light. Whatever You Say, Say Nothing is striking for its complexity and the humanity it takes care to show. Maybe that shouldn’t feel as striking as it does. But sure, I’m saying nothing.

Rachel Connolly is a London-based journalist from Belfast

Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2022 is at The Photographers’ Gallery until 12 June