Snapping pictures has long been a holiday pastime, driven by a deeply human desire to somehow take personal ownership of the sights encountered along the way, whether a crowded landmark or a secluded beach. I remember returning from family holidays and my parents dropping off rolls of film at the airport photo lab, and then the wait before the glossy packs of 6×4 prints would arrive in the post a few weeks later. These would be filed away in photo albums, always accessible but quickly forgotten. Looking back on images of me and my sister awkwardly stood in front of the Eiffel Tower or at Pompeii, I realize that there are very few pictures of us in our hometown of London. We all have a tendency to photograph the unfamiliar, as if capturing it will make it more knowable and less strange. By contrast, our everyday environment slips easily into invisibility, dulled by repetition.

Luigi Ghirri, an Italian photographer who began working full-time in the 1970s at the age of thirty (following a former career as a building surveyor), makes these details of the ordinary and the everyday strange once more. His images have the unaffected, handheld quality of holiday snaps, despite the fact that the majority of them were taken less than three kilometres from his home in Modena. Ghirri navigates through a world of common places and everyday experiences, focusing not on big cities or exotic locations but rather the suburbia and small towns that were within half an hour’s drive from him. He called these “minimal journeys”, in a brilliantly evocative turn of phrase.

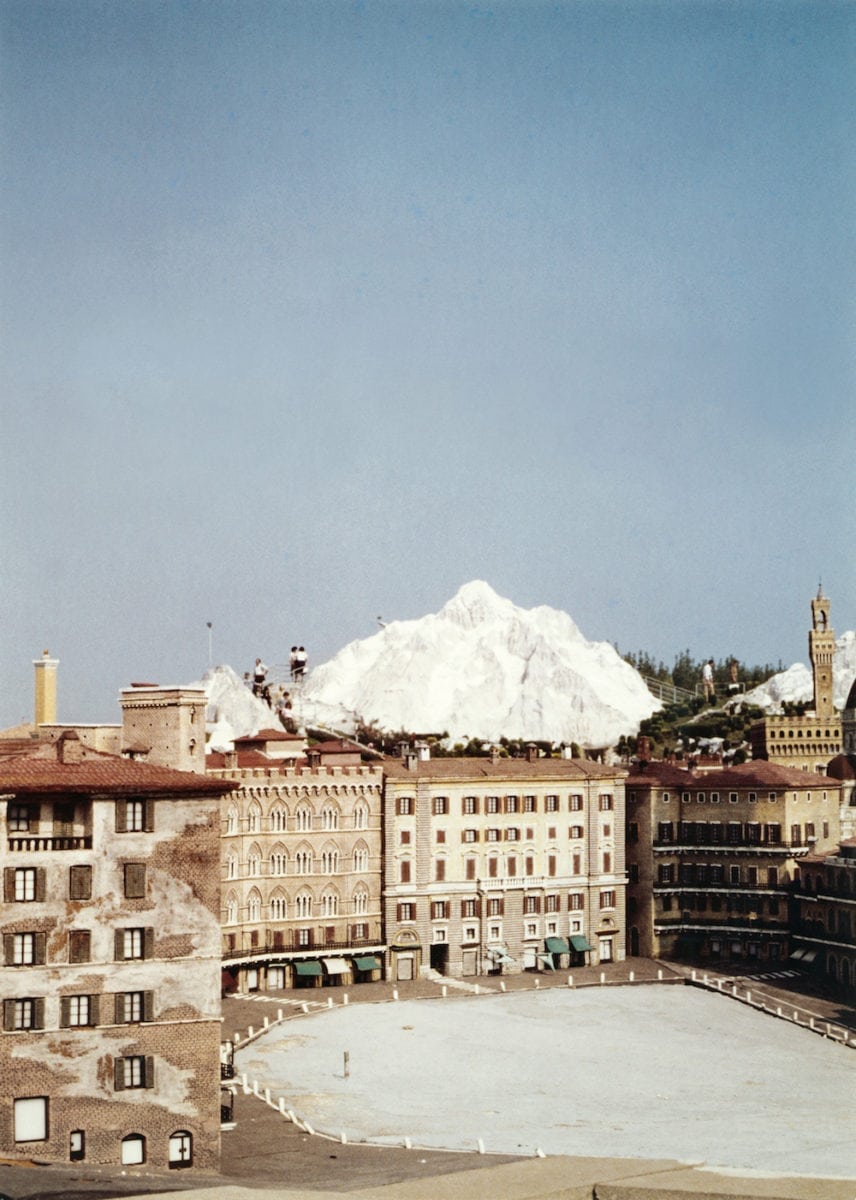

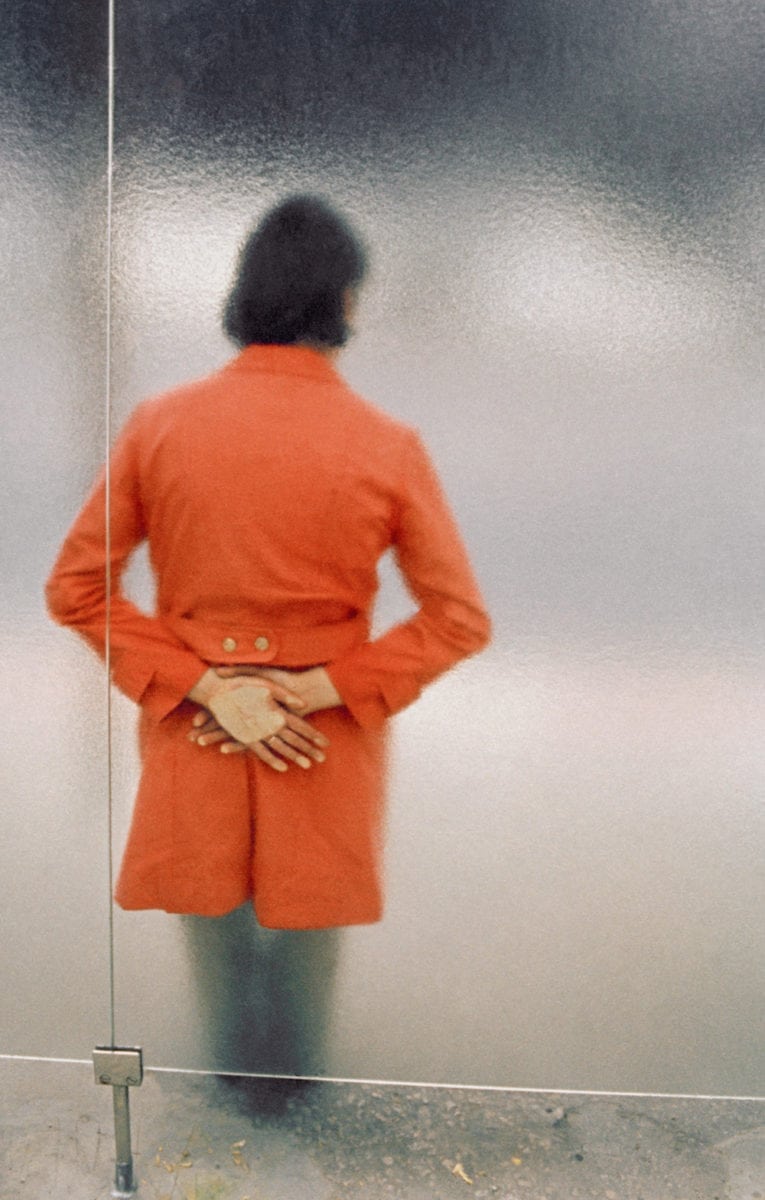

- Left: Engelberg, 1972; from the series Kodachrome, 1970-1978. Right: Rimini, 1977; from the series In Scala, 1977-1978. Both courtesy Mack

“His images have the unaffected, handheld quality of holiday snaps, despite the fact that the majority of them were taken less than three kilometres from his home”

Using just a small Canon camera, he would take his rolls to be developed at a normal photo lab, where he would return a few days later to pick up the prints. “I have never been interested in producing collectors’ items or attempting any visual enhancements,” he wrote in 1979, in the introduction to his first major solo exhibition, Vera Fotografia (True Photography) in Parma. Fourteen distinct series were presented in this exhibition, and form the structure for The Map and the Territory, a new survey of his photographs taken throughout the 1970s. The book (published by Mack and edited by James Lingwood) accompanies a major touring exhibition that will travel to the Jeu de Paume, Museum Folkwang and Museo Reina Sofia from 2018 to 2019.

Ghirri’s thematic groupings reveal the clear interests that directed his lens as he paced along residential streets and empty roads. Kodachrome, self-published as a book in 1978 (and the first series presented in his 1979 exhibition), focuses on images and advertisements seen in streets and shop windows. He chooses to photograph details, creating unsettling contrasts between seductive female faces and the hard grid of a shop shutter or brick wall. Posters crinkle slightly or tear away from the wall behind, revealing the absurdity of their projected fantasy amidst the humdrum nature of their immediate surroundings. In Paesaggi di Cartone (Cardboard Landscapes), he zooms in on found images of men, women and children, the type that you might find decorating the walls of hairdressers, opticians or a local photography studio, finding new meaning in their appearance when all-but stripped of their context.

- Left: Modena, 1970, from the series Kodachrome, 1970-1978. Right: Rimini, 1977, from the series In Scala, 1977-1978. Both courtesy Mack

The act of looking itself is never far out of sight in Ghirri’s images. He is interested in the illusion of the photograph, upheld by its framing and the power to choose what you leave in and what you cut out. “In photography, the deletion of the space that surrounds the framed image is as important as what is represented,” he writes in his introduction to Kodachrome. Views within views, frames within frames and images within images appear again and again, highlighting their artificiality and reflecting the endless onslaught of visual material that we each experience on a daily basis. It is an attitude that resonates in the age of digital images and social media, when we have seemingly reached saturation point and the proliferation of memes have fully broken down the boundaries between high and low culture. Ghirri was undoubtedly influenced by the pop art appropriation of vernacular imagery, and he embraces mass culture as a direct reflection of the time and place that he finds himself in.

“Views within views, frames within frames and images within images appear again and again”

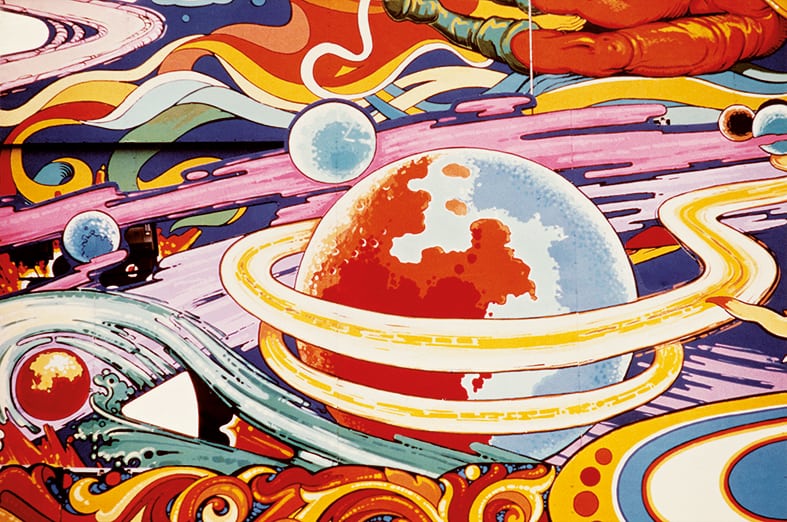

He visits funfairs in a series named The Land of Toys, in which scale is again played with and expectations distorted. Brightly coloured murals, pretend cityscapes and other temporary structures make clear the contrast between a cheerful scene viewed from afar and its wear-and-tear when seen close up. There is a double reality at play here, as humorous as it is quizzical. There is undoubtedly an element of kitsch to Ghirri’s outlook, seen particularly in his images of souvenirs, miniatures, billboards and postcards, and his broader interest in the gap between reality and its representation. He explains: “I have chosen to photograph objects described as kitsch, for within them we may often glimpse a set of important contradictions: the mismatch between the copy and the real thing, or between the past and the desire for its image in the present.”

- Left: Vignola, 1974, from the series Italia Ailati, 1971-1979. Right: Breast, 1972, from the series Diaframma, 1970-1979. Both courtesy Mack

This mismatch is the driving force behind all of Ghirri’s imagery. He looks for slippages where the strangeness of our everyday reality is revealed, seeking out moments akin to the discovery of the stage door within our very own Truman Show. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Atlante (Atlas), in which he photographed the pages of road maps using a macro lens. Drawn representations of palm trees and mountain ranges appear alongside the dotted demarcations of roads and territories. The jagged geometries of towns and the open blue abyss of oceans dance across the frame, challenging the boundaries of the photographic format itself. It is an approach that exemplifies his expansive, empathetic and inquisitive images, in which—like life itself—you are never entirely left sure about what is false and what is true.