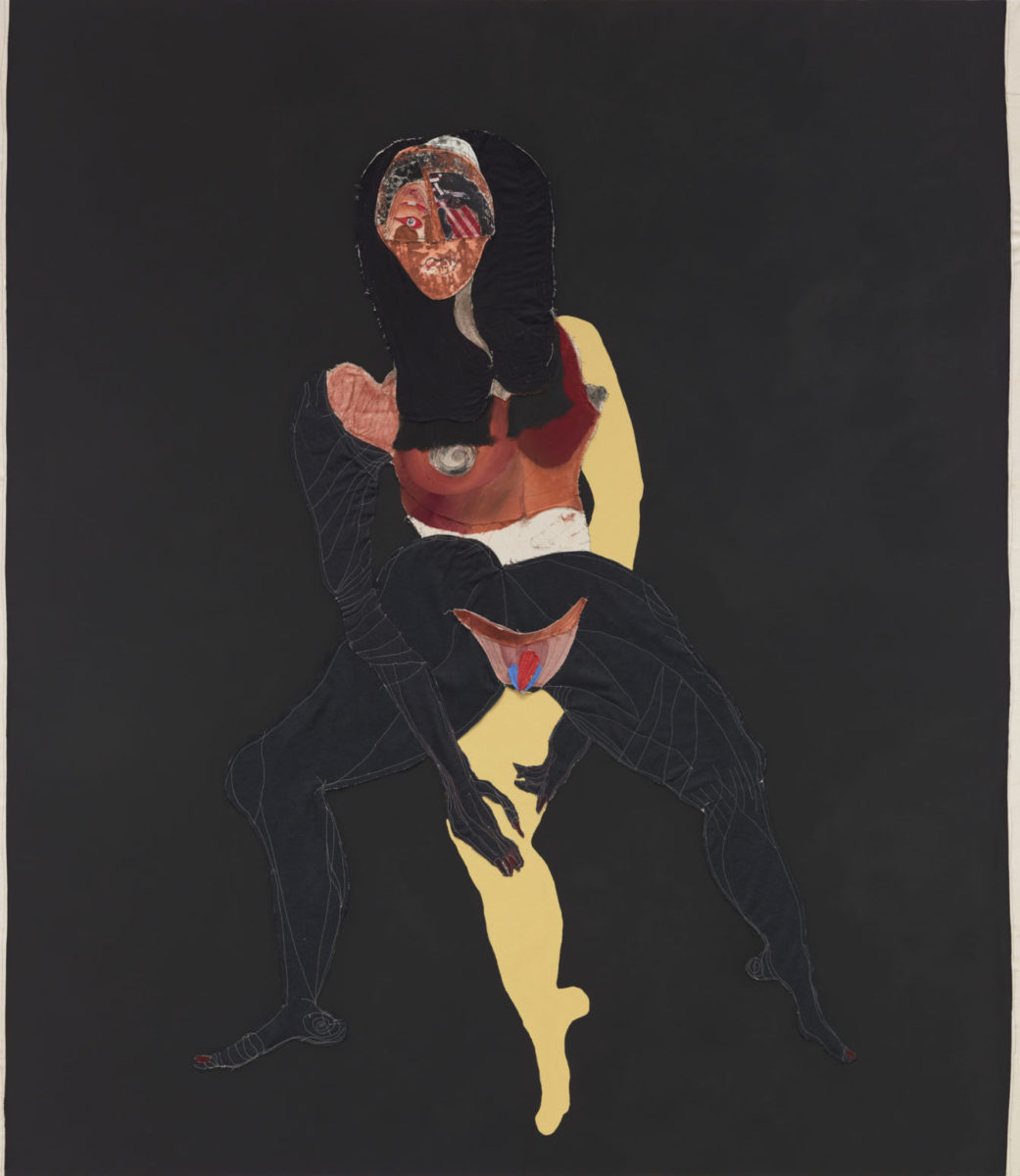

Tschabalala Self has a tendency to go big. Her colourful works—composed using a combination of painting, printmaking and collage techniques—are huge, often measuring more than two metres in height. She creates a new visual lexicon for the Black female body, building her exaggerated figures from scraps of fabric until their forms appear to almost strain away from the canvas behind. It is a patchwork approach, one that is reflective of the many references that filter into her field of vision, from the pop cultural to the art historical.

Born and raised in Harlem in 1990, Self was the youngest of five children. Her mother decorated their home with art bought on holiday in the Caribbean, South America and Mexico. They would buy art from West African dealers along 25th Street, which a young Self would occasionally sketch from on weekends. Later, she attended Bard College in upstate New York and completed an MFA at Yale, where she first began to explore the potential of the female gaze through an African-American lens.

“Originally, I felt most comfortable telling narratives that spoke through my own lived experience. So, being a woman, I wanted to make my own work as a reflection of myself. That’s the form I was most intrigued by, and the one I identify with the most,” she recalls. We are meeting in London, a metropolis that rivals New York’s cultural diversity, where West Indian grocers nestle alongside Chinese restaurants. Four paintings by Self were included in the recent Radical Figures exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery. This ambitious survey of contemporary painting placed her firmly within a new generation of artists who make use of the expressive language of figurative representation.

“I just want to leave my own impression, to make work that says something about my own life”

Self’s women are loaded with cultural associations rooted in her own personal narrative and racial identity. She resists western ideals of beauty, focusing instead on body shapes that have often been excluded from the art historical canon. “If you’re looking at the ideal physique in the African diaspora, it is more of a robust, larger woman,” she says. “I personally lean towards exaggeration in the forms, just as a matter of taste and preference, because I think there’s this cultural affect to play with. If the body is larger, having more weight to it and being more voluptuous, there’s more material to build in and manipulate pictorially. A lot of my female forms are more robust for that reason, and in my mind, they feel more powerful.”

Early in her career, Self used imagery from magazines and music videos, such as 2Pac’s “I Get Around”, reworking them into paintings and collages in order to challenge and reclaim the objectification of black women in pop culture. “I absorb all that stuff as well; I’m a consumer of all those images just like any other person. I can’t pretend that I’m making my work in some kind of cultural vacuum. But also, given the specificity of my own experience— being a Black American, having grown up in the nineties in a Black community and being raised in Harlem—I’m aware of where the roots of that aesthetic come from. It’s in the Black culture of the diaspora from the continent to the Americas.”

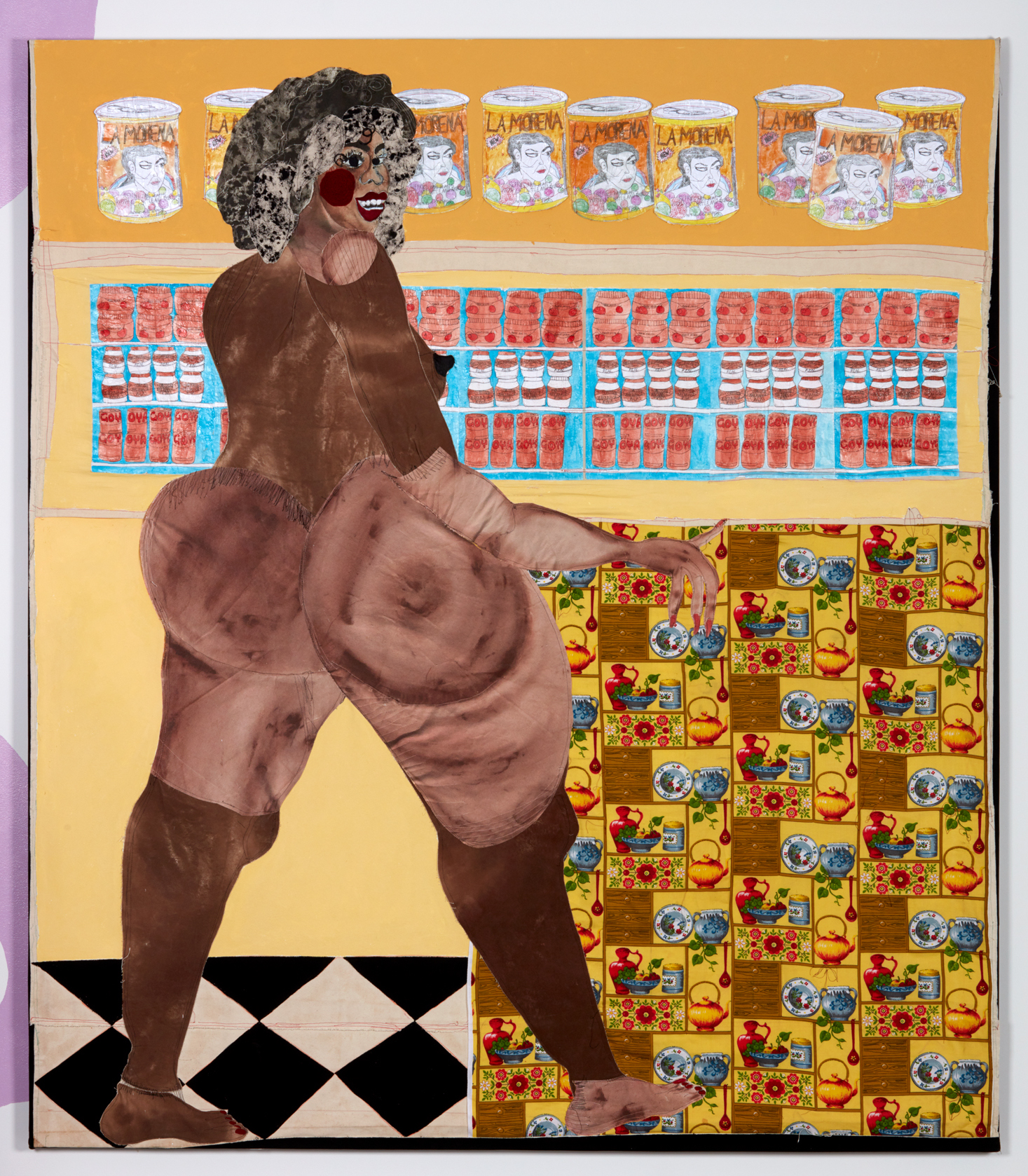

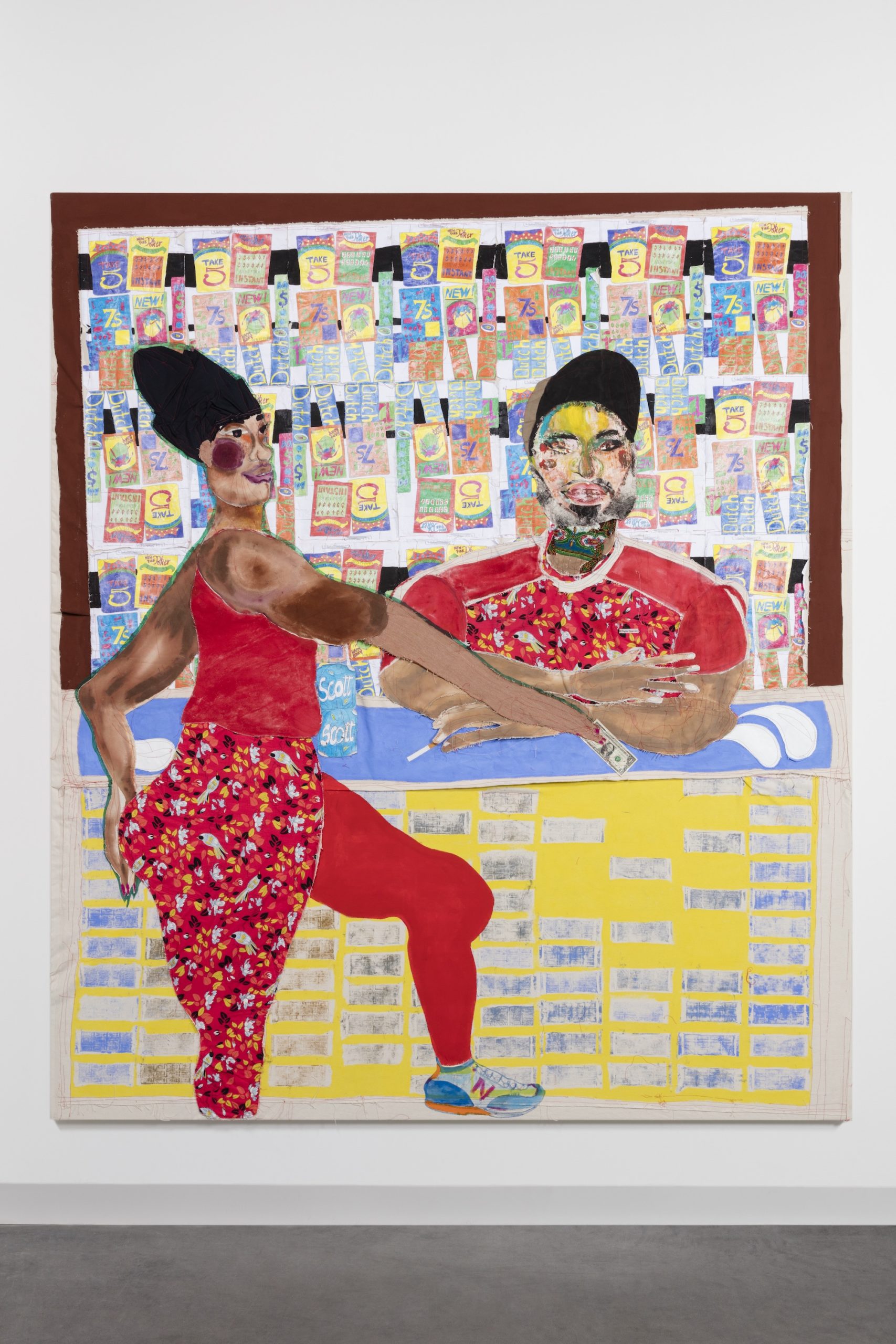

- Thigh High (install), Pilar Corrias, 2019

In her patchworked imagery, female figures straddle the erotic and the quotidian. A yellow fabric printed with red strawberries is cut into a female torso in Out of Body (2015), while in Milk Chocolate (2017) a woman made from delicate brown cotton displays her buttocks. There is a tactility to these textiles which feels at once illicit and deeply familiar, like a childhood duvet cover that you lost your virginity on. “Some of them are close to me, they’re sheets or old clothing. Some of them come from my mother’s fabric collection; she collected lots of fabric. I purchased some of them from different places, from different parts of the city, or the tri-state, or Florida, or abroad, picked up here and there.”

“I think it’s good to see a reflection of yourself. Representation matters”

Self explains that she is drawn to the cultural energy of these objects, with their mishmash of designs, textures and patterns. “Certain fabrics hold ideas or memories, and all that is already living within the object, so when I bring that object into my own practice and into my own work, some of that energy is transferred.” Her aim is to engage the viewer’s senses, encouraging them to have an active relationship with the painting. “I want them to feel other kinds of sensations, even if it’s just an artificial sensory kind of thing. It keeps and holds their attention for longer and allows them to go deeper within the work that they’re looking at.”

What does she make of the lingering snobbery towards craftwork or “applied” art within the world of fine art? “I don’t really give too much energy to the conversation. I think most of painting is really just about having the confidence to claim that your work is a painting. But I think a lot of these hierarchies are based on other ideas that I don’t subscribe to either. A lot of them are rooted in misogyny or racism, or other issues that think of people and the things they produce as ‘other’. Most hierarchies are oppressive and based primarily on opinion and not fact.”

At thirty years old, the artist is self-assured and poised. She answers succinctly, giving careful consideration to her particular choice of words. Already, she has had solo shows at Institute of Contemporary Art Boston and Pilar Corrias in London, alongside her Bodega Run series (2015–2019) shown in London, New York and Shanghai, which culminated in an immersive installation in the lobby of the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Bodega Run examined the neighbourhood convenience store, commonly found in Self’s own locale of Harlem, as an encapsulation of racial and economic threads within a diasporic community.

- Pant, 2018 (left); Close Up, 2019 (right)

For the series, she created line drawings of food typically found on the shelves, and paintings of customers, placed within an installation featuring a tiled linoleum floor and an electronic LED store sign in the window. “The bodega was a very specific project based on cultural exchange. The people who own the shop are generally of Afro-Latin descent, like Dominicans or Puerto Ricans, and the people who patronise the store are the residents of the community, a lot from West Africa but all of the Americas, and South and Central America as well,” she explains, before pausing. “If you’re talking about the store, you can talk about the community at large. But it’s also a transactional space, which adds another layer of complication to it, because I can’t say it’s entirely positive, and there are some ways in which the store exploits the residents that utilise it.”

“I’m not sure how much longer the bodega as I know it will exist. The neighbourhoods are changing”

Self continues to live in Harlem, not far from where she grew up. “At the end of the project, I felt like the store was kind of analogous with a lot of the dynamics that exist within communities of colour in America. Things are not necessarily entirely positive or negative, but despite that, they exist and should be acknowledged and remembered. I’m not sure how much longer the bodega as I know it will exist. The neighbourhoods are changing, communities are changing—they’re just not what they were.”

While Bodega Run gives visibility to a unique form of community that is often overlooked, and one that she is deeply familiar with, her figurative work also shines a light on subjects who continue to be marginalised. Is her work an act of defiance? “I wouldn’t say that it’s defiant, but I do want there to be some kind of record of these things. And also, for me, it feels exciting to be able to make a painting of something that there hasn’t been a painting of before. I just want to leave my own impression, to make work that says something about my own life as well.”

Self paints with one eye on the future, and another on the past. “I’m hoping people will see my work and think, ‘Oh we were there too.’ Because histories are not always based on reality—they’re based on who wrote the histories. Who knows what the future of Harlem will be? Hundreds of years from now, people might not remember that anyone like me ever lived there. So, my paintings exist, and there will be no denying that we were there.” For now, she is focused on the immediate impact of her work as a signal for greater change to come. “I want people to feel validated by looking at my work. I don’t want to say uplifted, but I think it’s good to see a reflection of yourself. Representation matters.”

Top portrait by Benjamin McMahon for Elephant

This article first appeared in Elephant Issue 43

BUY NOW