Increasingly ludicrous rents, soaring university fees and the rapid gentrification of previously artist-friendly areas make it easy for all of us to languish in rose-tinted visions of the London of yesteryear. “Back in the day” it seems the capital was bursting with creativity spawned of an angry, youthful energy that stuck two fingers up to “the man”—not to mention the Iron Lady. Art could seemingly flourish outside of formal institutions thanks to affordable art schools; grants; benefits schemes; pre-digital human interactions and collaborations; and crucially, a prevalent squatting culture that many have cited as the key factor that enabled them to continue their practice.

Increasingly ludicrous rents, soaring university fees and the rapid gentrification of previously artist-friendly areas make it easy for all of us to languish in rose-tinted visions of the London of yesteryear. “Back in the day” it seems the capital was bursting with creativity spawned of an angry, youthful energy that stuck two fingers up to “the man”—not to mention the Iron Lady. Art could seemingly flourish outside of formal institutions thanks to affordable art schools; grants; benefits schemes; pre-digital human interactions and collaborations; and crucially, a prevalent squatting culture that many have cited as the key factor that enabled them to continue their practice.

While the majority of squatters are sadly forced into their situations through homelessness, for the sake of brevity this piece focuses solely on arts-centric squats. These have offered accessible, alternative living and artist spaces for the likes of Neo-Naturist co-founders Christine and Jennifer Binnie, Damien Hirst, Cerith Wyn Evans, Tracey Emin, Peter Doig, Jimmy Cauty, Grayson Perry, Jeremy Deller and Genesis P-Orridge. Joe Strummer’s pre-Clash band The 101ers was named after his Maida Vale squat, where The Slits often rehearsed—the band’s guitarist Viv Albertine was taught a “conceptual” approach to playing by Keith Levine, a fellow squatter and co-founder of The Clash and Public Image Ltd (PiL). In 2004 the !Wowow! Collective, which included artist Matthew Stone and fashion designer Gareth Pugh, formed their squatted artist-run space in Peckham.

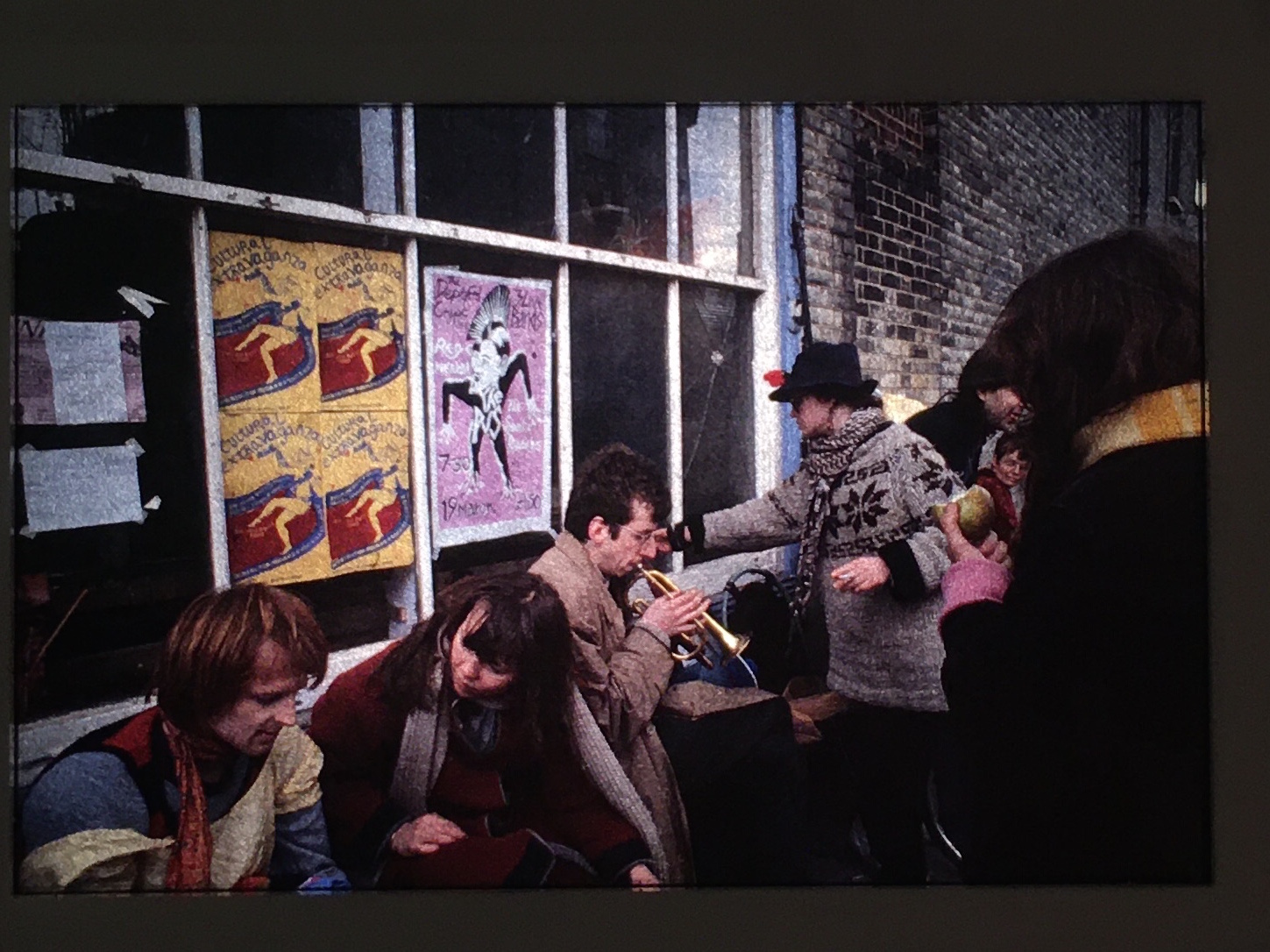

From the late 1960s, squatting increasingly became an active, political lifestyle decision that conflated art and the everyday by circumventing the establishment—echoing some Dadaist and Situationist ideas. Squats facilitated radical new magazines, political organisations, and craft and print workshops, alongside practical enterprises like crèches and food co-ops, all of which served to support the positive and creative potential of residents.

“People enter squats because they offer the time and space to be an artist—or they become that by living there”

Albertine has described the 1970s as a time when women were still largely expected to follow the marriage/kids/eternal housewife trajectory—which she certainly had no interest in. Thankfully, progressive women-only squats were flourishing, inhabited by the likes of Spare Rib collective member Anny Brackx and feminist bookshop Sisterwrite’s co-founder, Lynn Alderson. These provided safe spaces for visible lesbians and the burgeoning women’s liberation movement; shared-childcare; and escape from domestic violence—all of which enhanced women’s capacity for creativity, by offering both support and freedom in terms of time and money.

During the early 1980s, Bebe Geen squatted in Camberwell, receiving council funding as a “feasibility study”. Such government actions were a double-edged sword: Geen says squatting opportunities were irrevocably eroded by Thatcher’s “right to buy” housing act, which pushed for council house residents to buy their properties. “People are happy to be given a house, then they keep quiet and that energy is dissipated—it’s about breaking people’s spirits,” she says. “The city was turned into a money-making powerhouse. It wasn’t like that before.”

“Squatting was the only way I could subsist on a small amount of money and carry on doing my artwork after graduating”

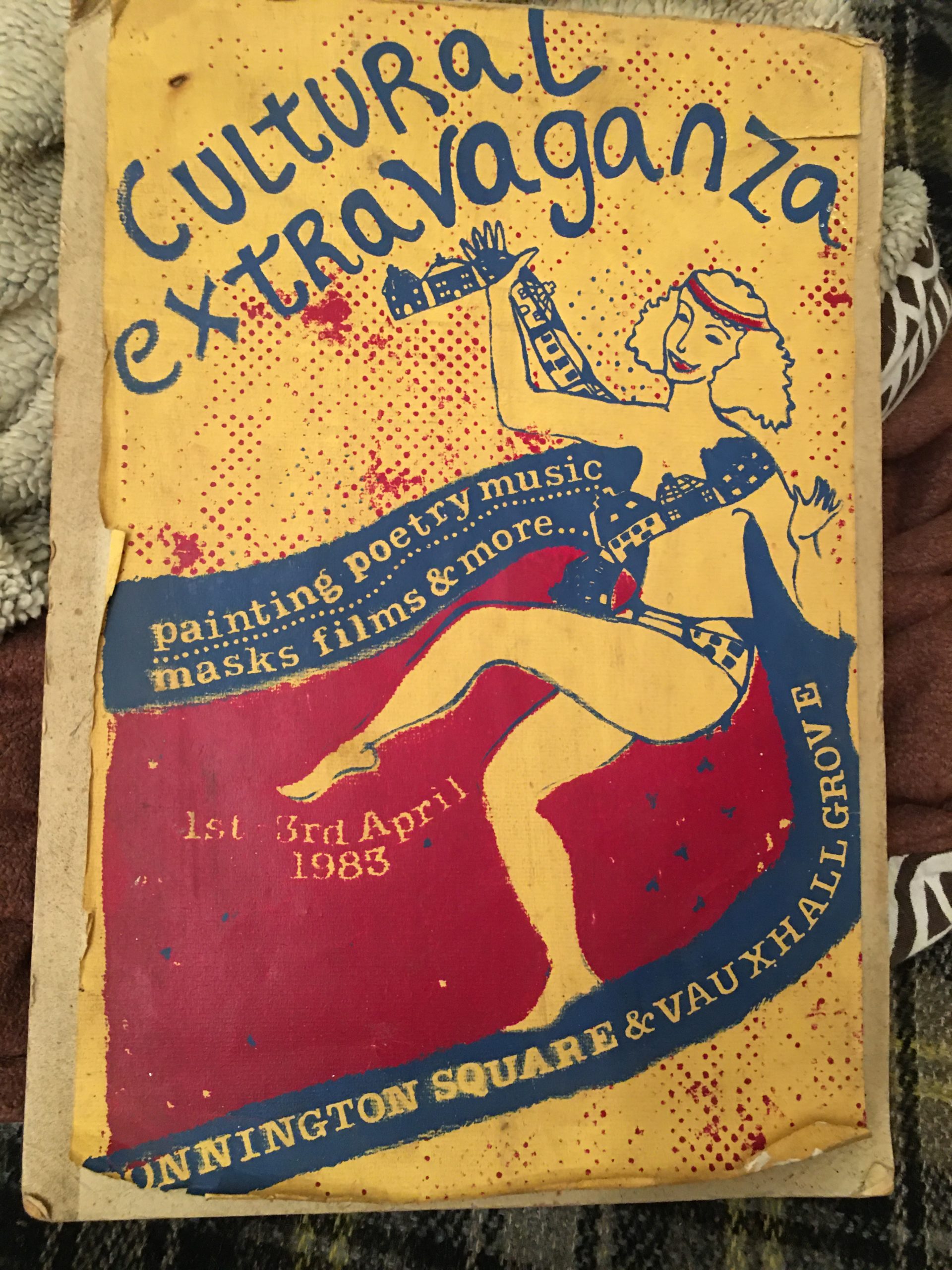

Geen was among the first occupants of Vauxhall’s famously squatter-occupied Bonnington Square, which soon boasted a nightclub (hosted acts including The Jesus and Mary Chain); as well as a vegetarian café and community garden, which both remain open today. Geen says the squatters befriended any initially suspicious neighbours, who later embraced their artworks.

Artist Jimmy Cauty took full advantage of the council’s provision of tools and £3,000 (paid directly into his account) for “upkeep” of the squatted Stockwell house he moved to in 1980, which became part of the North Lambeth housing co-op. He used the cash to build the “Trancentral”, which birthed his and Bill Drummond’s hugely successful band The KLF.

In decades past it was also easier for creatives to scrape by on government benefits, or through initiatives like the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, which was ostensibly launched to provide guaranteed income for business founders. It was used by Tracey Emin, Creation Records head Alan McGee, and Viz magazine’s founders. At a time of mass unemployment, this scheme cannily lowered the numbers by classing claimants as “self-employed”—not unlike the zero hours contracts, gig work and part-time minimum wage jobs that boost government stats today.

Like many artists, Cauty has spoken of squatting being a lifestyle choice as much as a necessity. However, then as now, it was tricky to live and make art in London. “Squatting was the only way I could subsist on a small amount of money and carry on doing my artwork after graduating,” says Geen. Artist and former squatter Steve Lowe echoes this: “We were art students surviving in London the way we could in the 1980s,” he says. “I had a whole room for my studio when I was about 18—I’d never have been able to afford that without squatting.” For Lowe, finding a free home proved remarkably simple: the plywood used to secure doors and windows was easily removed in broad daylight.

Today, through his arts platform L-13 Light Industrial Workshop, Lowe works with artists known for their involvement in music and countercultural living, such as Cauty, Harry Adams, Billy Childish and Jamie Reid. L-13’s ethos is to “promote a playful polemic spirit, irritate and offend some delicate souls in the big bad world of culture and politics”—a sensibility aligned with that of many squatters during the late twentieth century.

“From the late 1960s, squatting increasingly became an active, political lifestyle decision that conflated art and the everyday”

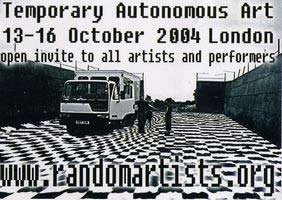

Art-based squatting as a creative reclamation of otherwise ignored spaces (not the lawless, drug-fuelled versions the media often portrays them as) continued into the new millennium. Jess, part of the Random Artists collective, squatted from 1999 until 2008, co-founding Temporary Autonomous Art (TAA) in 2001. Inspired by the 1990s sound-system culture that combined music and elements of visual arts in squatted spaces, a key aim was to promote women’s inclusivity and create an alternative to “sterile” or “elitist” exhibitions.

TAA has hosted exhibitions in abandoned pubs, offices and children’s centres, places that once signified community cohesion. It aims to reignite the lost sense of collectivism through events that prove everyone—regardless of background, age or education—can be artists. Police were largely kept at bay once they saw the spaces’ ambitious artworks and its respectful creators/inhabitants. According to Jess, squats offer unique sites in terms of their cost-free, large-scale sites: “It feels more important than ever to have safe, community spaces that inspire creativity.”

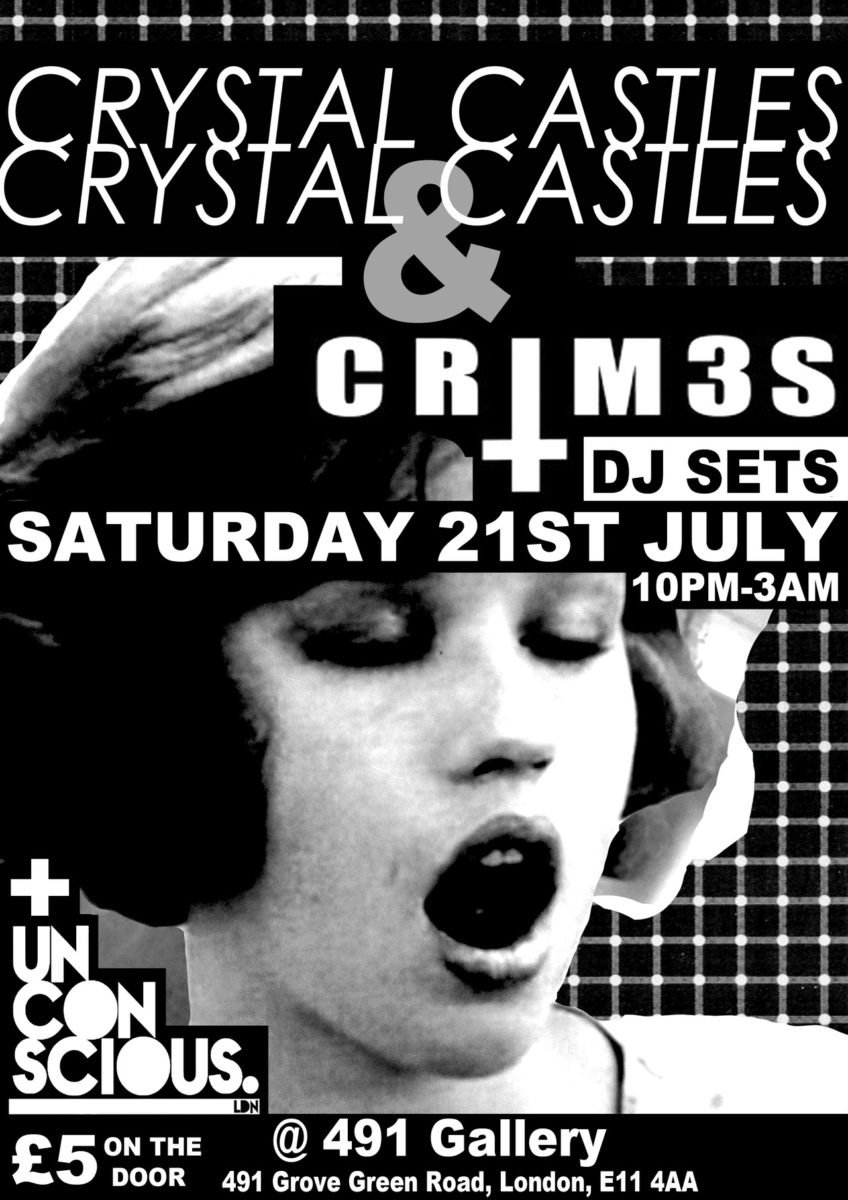

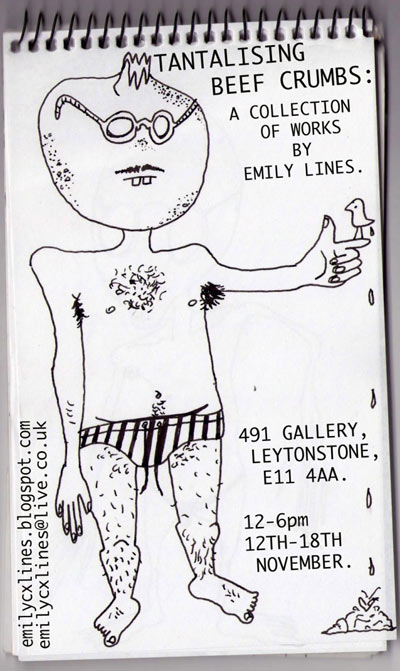

491 Gallery and music space Vertigo were founded that same year, when artists occupied and transformed a former factory turned drug den in Leytonstone. 491 used traditional polished, white-wall aesthetics to show multi-disciplinary artworks upstairs; while other spaces hosted theatre, comedy and music performances, film screenings and workshops such as sculpting and photography.

“It’s easier to deal with experiences when you can isolate yourself and turn them into artistic ways of documenting life”

Musician Ben moved into the space in 2005, having been a regular visitor for years. “I felt like I’d come home,” he says, adding that while large shared spaces inevitably involve personality clashes, a sense of unity prevailed thanks to the “overarching agenda that we were there to do art, music and encourage culture. It was a special place.”

The gallery remained open for over a decade. “We were well established: the council knew about us, but we were never trouble. There were parties all the time, but no one ever got hurt: there were no bouncers, because if you tell people ‘this is your place too, make yourselves at home’, they look after it,” Ben adds. In 2012, Transport for London sold the building to property developers, who soon demolished it to build flats. 491 Gallery closed in 2013, with Vertigo following three years later.

Such innovative places are increasingly precarious and less visible today, but they do still exist. A vast North London squat that opened in around 2013 hosts music and visual art workshops. It allowed resident Andres Posada, who has no formal artistic training, to pursue analogue photography (which he now teaches), and painting. He shares Jess’s idea that regenerated spaces can offer transformative opportunities for those who had not previously considered themselves to be creative: “I see artistic expression as healing, like therapy. Everyone needs to create. It’s very human-centric.”

Posada’s art focuses on working with communities; with squats offering a perfect vehicle for agency and motivation in people living on the margins. Working together to build a space creates bonds through shared responsibility, achieving something together with visible changes,” he says. “People enter squats because they offer the time and space to be an artist—or people become that by living there.”

However, filmmaker and squatter Dasa sees no direct link between art and squats, but suggests that driven artists already working on a project have more potential to flourish. “A space open to all, that’s likely to be demolished, frees you from worrying about things like criminal damage or galleries telling you what to do. Squatting isn’t automatically creative, but it’s very liberating: there’s freedom to experiment and live within a community.”

Photographer Pawel Dziemian began living in London squats around 2009, after graduating from art school in Poland. He also reckons that squats are unlikely to engender creativity: “Squatting was making me depressed,” he explains, while adding that photographing the squats allowed him to cope. “Looking through the lens—searching for an image or crop—is a defence as you’re not looking straight at reality. It’s easier to deal with experiences when you can isolate yourself and turn them into artistic ways of documenting life.”

“While it remains legal to squat industrial buildings, such spaces are generally short-term and precarious”

It is not easy living in dilapidated spaces that often lack heating, plumbing and electricity, with a constant fear of eviction or arrest, and where, according to Dziemian, residents were often “tribal”. Jess also feels the squatting scene has become more “elite and insular—it should be about accessibility, not becoming more marginalised. There’s a sense that you’re either in a squat, or out of that community.”

Yet an idealistic view of squats as artistic utopias of like-minded community values often prevails. They offer space to make and show work without gallerist demands and arduous grant applications, and freedom from the usual labour-based time restrictions necessitated by London’s rental prices. But unbridled freedom is not always positive. “People can become very down when they have no structure or responsibilities,” says Dasa. “You need some sort of framework as an artist—money and space isn’t the recipe for creativity. It helps not to worry about money, but you can become lazy.”

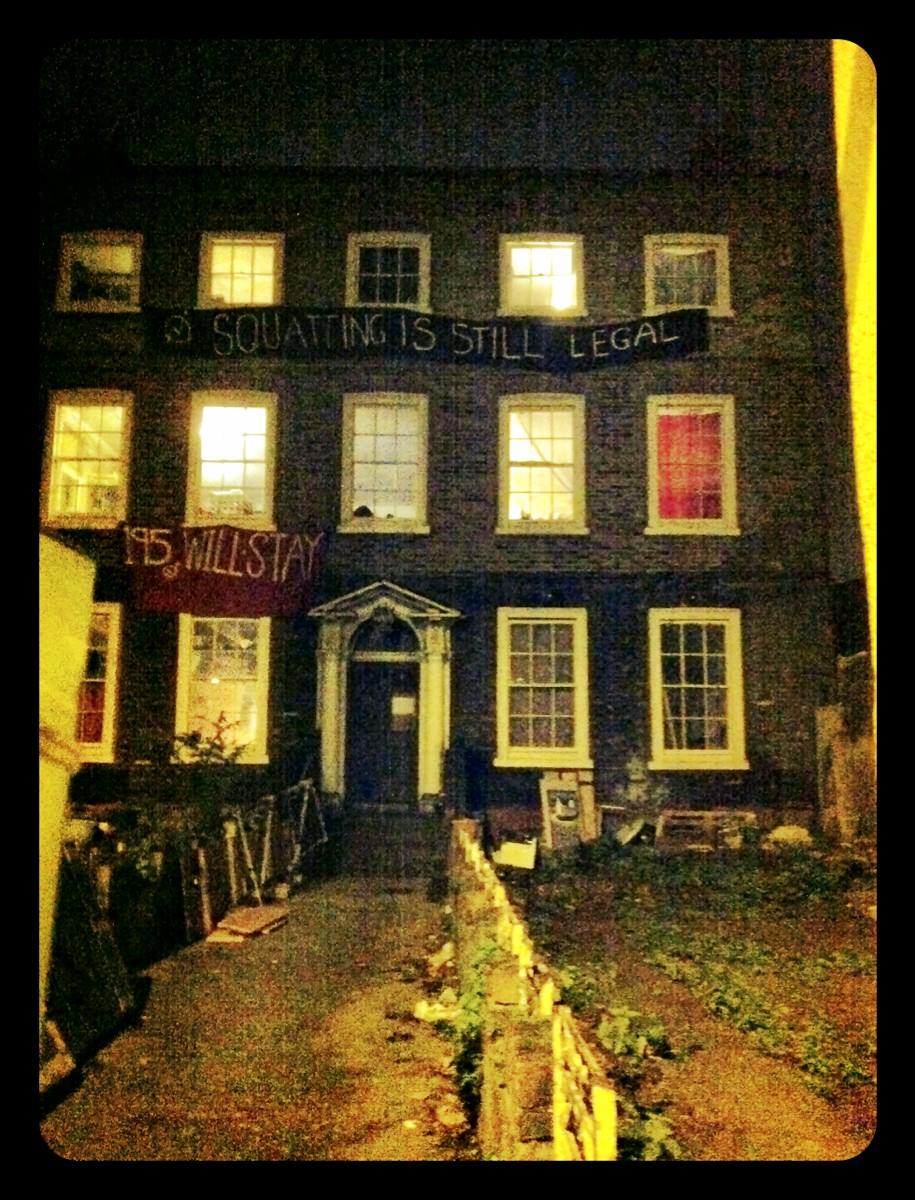

Even so, the decline of such spaces due to London’s rapid redevelopment and most significantly, the 2012 law making squatting residential buildings illegal in England Wales, has contributed to the death knell of the vibrant, DIY-based confluence of art, music, communality and activism that once characterised the city. While it remains legal to squat industrial buildings, such spaces are generally short-term and precarious; allowing little time for the creation of a cohesive, collaborative art-space.

For example, many building owners are taking advantage of property guardianship schemes, which charge not-insignificant rents (anywhere between £200 and £800 a month) to live in spaces like former schools, offices, care homes and hospitals. Dasa says guardianships “destroyed squatting—they’re just a loophole so companies avoid paying empty property tax. You have no autonomy.” They often only accept employed people over 21; many require at least one month’s deposit, bank statements, passport scans and employer references. Usually, no guests, couples, room modifications or smoking are allowed—let alone exhibitions or gigs. No such rules apply to squats; yet guardianships can be similarly dicey in terms of things like decent and safe electricity, heating or plumbing.

For example, many building owners are taking advantage of property guardianship schemes, which charge not-insignificant rents (anywhere between £200 and £800 a month) to live in spaces like former schools, offices, care homes and hospitals. Dasa says guardianships “destroyed squatting—they’re just a loophole so companies avoid paying empty property tax. You have no autonomy.” They often only accept employed people over 21; many require at least one month’s deposit, bank statements, passport scans and employer references. Usually, no guests, couples, room modifications or smoking are allowed—let alone exhibitions or gigs. No such rules apply to squats; yet guardianships can be similarly dicey in terms of things like decent and safe electricity, heating or plumbing.

“Squatting shows the capacity for altruism and the sharing of space, time and knowledge with others”

Artist David Shillinglaw, who is now based in Margate, says that the squatting scene he’d known in London has been lost to corporate greed—“There’s no corner of London that hasn’t been monopolised”—and increased CCTV. He laments the decline of squats, because they have a far broader impact than most realise: “They’ve got social significance, showing how a city works, if a city’s safe, and how people respond to a sense of community.”

Aside from creative collaboration, their very formation also forces people to work together, learning and sharing skills that will always be useful, from basic plumbing and building repairs to rudimentary legal knowledge. This side of squatting shows its capacity to promote altruism and sharing of space, time and knowledge with others; which have been largely lost in the fast-paced modern landscape.

For many artists, squatting has always been more than just a place to live. It provides a foundation for new modes of creativity, community and political resistance. Squats flourish in times when cities feel hostile: in the face of unemployment, austerity, oppressive social codes; when young people feel angry and dispossessed, or helpless at the apparent impossibility of living as an artist in the capital. These issues are all too familiar in Brexit-blighted 2020, and though squatting might be increasingly difficult, the fact that defiance and resistance are inextricably linked with art-making remains.