Albany- Uman is a prolific painter whose kaleidoscopic artworks transcend space and time. Her technicolour, large-scale paintings draw from a rich vocabulary of symbols that have accumulated over her life and crystallised in her dreams, from visits to her aunt in the Chalbi desert of Turkana in northwestern Kenya as a child to the vast starry skies and pastures of her home in Roseboom, New York. Her current exhibition, I Want Everything Now, which runs until June 17th at Nicola Vassell Gallery in Chelsea, presents a sweeping survey of her recent paintings as an entry point into the artist’s world.

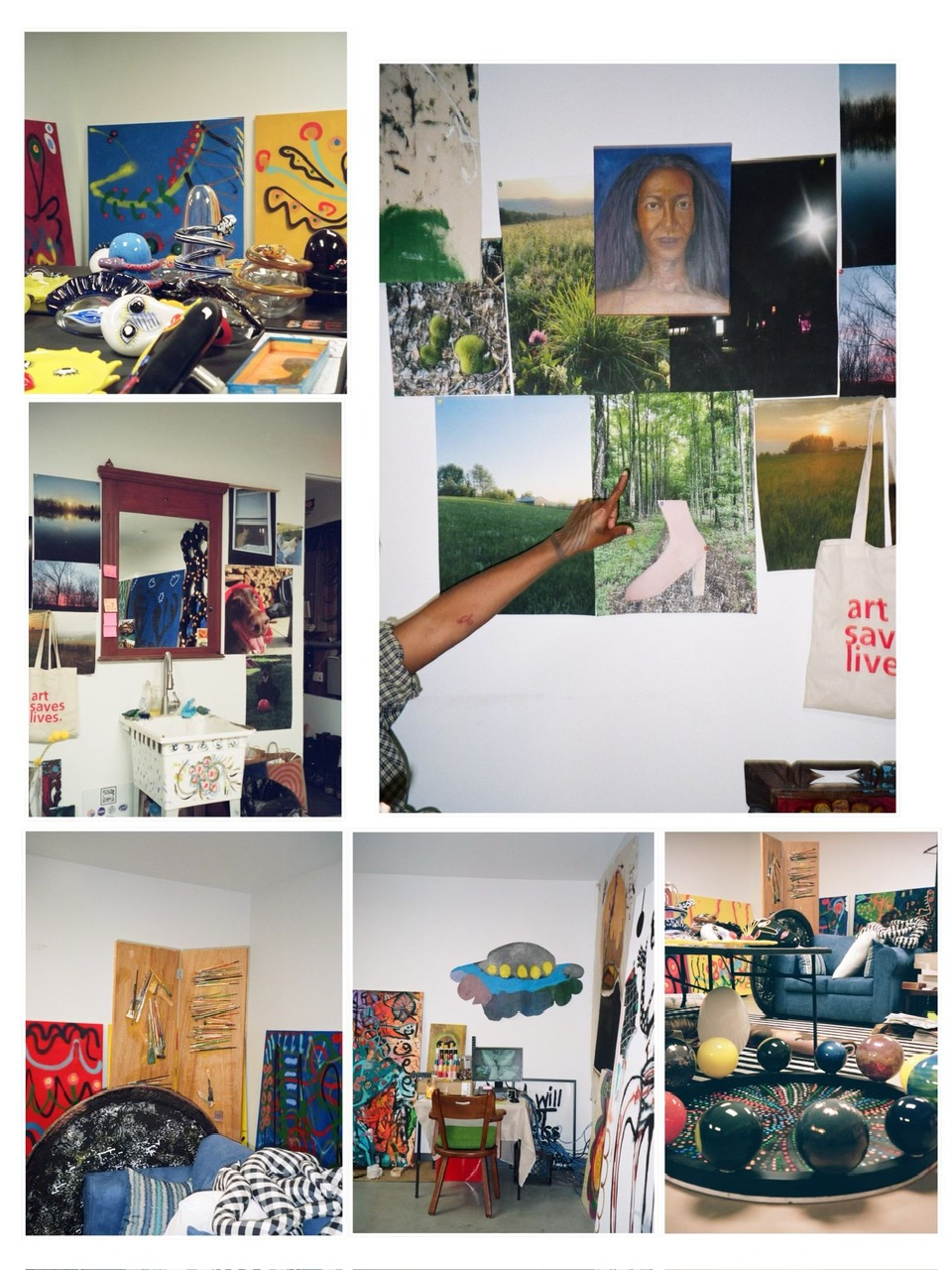

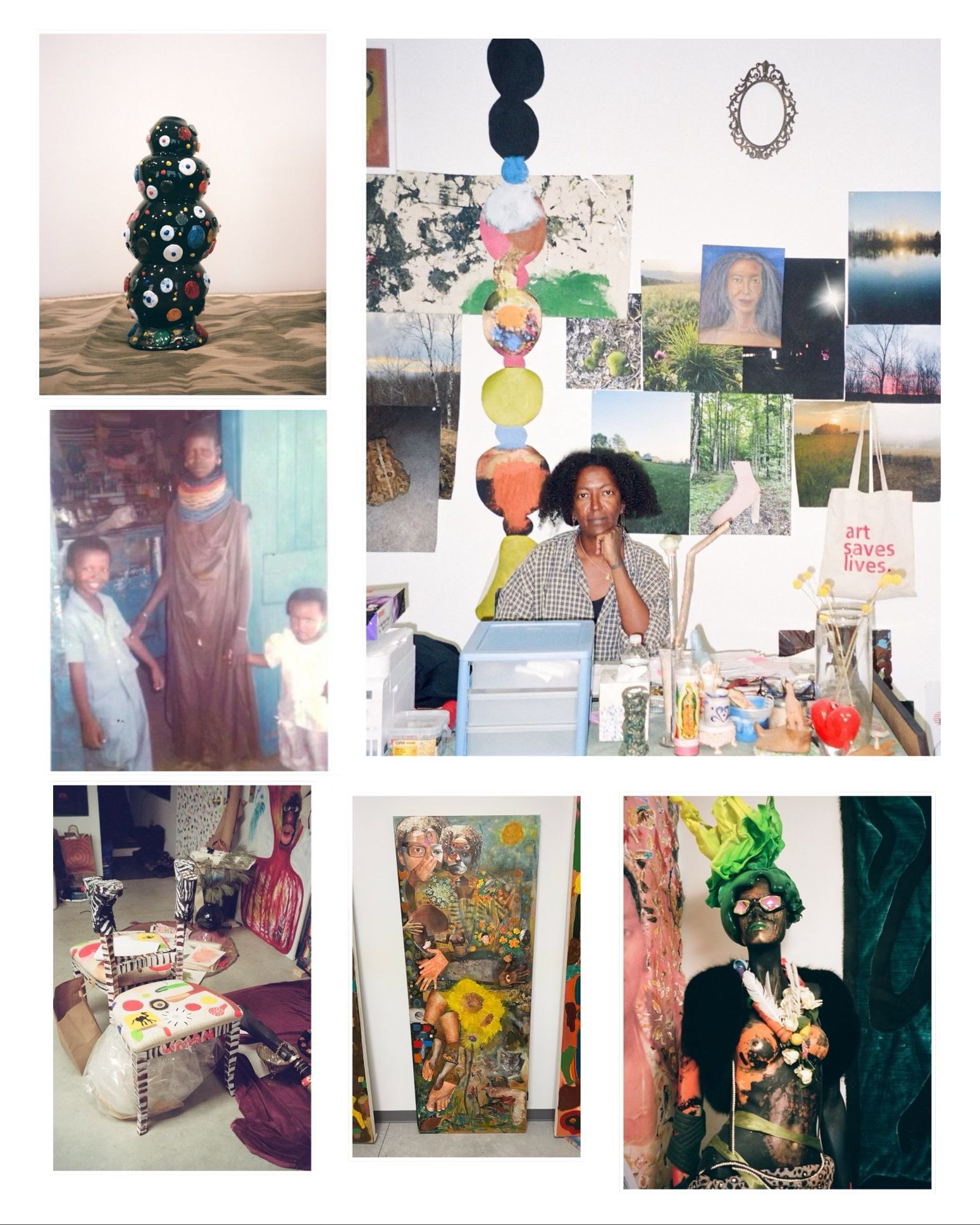

In her studio in Albany, New York, Uman’s idiosyncratic vision spills over from her canvases onto every corner. Her multi-room building is home to a neatly organised labyrinth of paintings — some filed away in rows, some propped against walls, some jutting out into the middle of the room — along with countless collages, works on paper, images pinned to walls, soft sculptures, glass works, and a lifetime’s accumulation of trinkets, found objects, photocopies, and ephemera. Outside the expansive (eight thousand square feet) brick building, little besides a planter with neat rows of pink carnations hints at the colourful world within.

“I’m obsessed with lamps,” she tells me inside her studio. “There is a lamp on the street, and it shines into my window upstairs. I always look at it; sometimes, I stand outside in front of it.” This same lamp appears across her paintings at Nicola Vassell Gallery: in Me Lights, 2022, a three-bulbed streetlight floats above a bench suspended in a shadow; here in her studio, it has materialised again, towering over us, a minimal sculpture made from metal scraps with a curved neck waiting to be affixed a glass egg-like lampshade. The urban marker is a new phenomenon for the 43-year-old artist who spent the better half of the last ten years atop her mountain before she found a space with an easier route from New York City to welcome studio visits from the art world.

Albany is an old, nondescript city dotted with green parks. New York’s capital feels like a big small town with the addition of skyscrapers, brutalist architecture, a state university, vacant storefronts, and industrial areas like the one where the artist’s studio is located. While the municipality isn’t known for being particularly artsy — most of Uman’s artist friends are either elsewhere upstate or back in Manhattan — underneath the Empire State Plaza building, 92 works by American modernists, including Calder, Rothko, and Guston are on display in a collection owned by New York State. Across the city, on a tree-lined street off the highway, nestled between a flooring store and an auto shop, a new artist is positioning herself to join the canon.

Uman’s front door opens into a space used as a gallery and office. Of course, the sparsest room in the building still has artwork covering the walls, resting on every surface. The first room down the hall (also lined with paintings) is overflowing with works on paper. It has lived many lives in the past year and a half, the artist tells me. At one point, the floor was strewn with drawings and collages; she would slip on shoe covers and traverse the space to view her collection. At another point, its white walls were covered ceiling-to-floor with fabric. Now, a bed sits in the middle of the room, framed by larger works on the walls.

Paintings, collages, drawings, and photocopies are stacked on a long table and in piles on the ground. Collages made from the artist’s glamorous self-portraits taken in New York in the early aughts peek out from more recent landscapes from her life upstate: a cow rendered in colourful dots, a photo of a canvas propped up on a green hill in her backyard. A thick snake of gold paint glued on a minimal sketch serves as a prototype for a series of rugs that were later handmade in Nepal.

Down the hall opens up into the largest room full of her monumental paintings and glass sculptures: suns, hands, orbs, translucent vases, and faces (the product of a fruitful week-long glass residency the artist recently completed in Oakland). In Uman’s practice, colours and images often reappear across series. “I get bored so easily,” she says. “I like to go here, and then go here, and then go here,” she points to a row of red, yellow, and blue canvases she is currently working on. “I would take this green colour that I’m using or this yellow colour, and then maybe I’ll go add a dot there,” she waves her hand across the wall. “It is all very spontaneous and free-flowing.”

Everything Uman touches becomes an extension of her practice: a long white coat with soft splotches of blues and greens hangs against a wall with a paper sunflower sticking out of its collar, sinks and doors are transformed with colourful dots and whimsical patterns, chairs are painted and repurposed as sculptures.

“That’s my mum,” she says as we stand in front of an image of a beautiful young woman printed onto fabric, a distant life memorialised here in the corner of the room. “I hope she will see it one day,” she muses on her art, lingering on the far-off idea for a minute. “My dad said to me, ‘You should do Islamic calligraphy instead.’ I said, ‘But I’m a painter.’ He has no idea what that really means or what it entails.”

Later I looked up calligraphy and found the definition: “the art of giving form to signs in an expressive, harmonious, and skilful manner.” Whilst her dad might not understand the role of an artist, in some sense, he gets what Uman is doing, except her calligraphy is singular, personal, a language of symbols built on memories and dreams. She is a collector of life experiences that find their way into motifs in her art— cows, camels, snakes, birds, the blues of the Mombasa coast, the greens of New York’s mountains, and flowers.

The multidisciplinary artist learned to paint before she had a name for it: as a child, she drew on walls and desks at school in Kenya, gazed in wonder at the intricate carvings on the doors of mosques, and dreamed of a faraway land where she could be herself freely. At a young age in East Africa, creativity was seen solely for its utilitarian potential — calligraphy, architecture, transportation — and art as a vocation in-and-of itself was discouraged if even recognised at all. Uman saw the process of art-making as a portal to another, more nurturing world. And in that sense, isn’t all creativity utilitarian? Art fulfils a human need to remember, to belong somewhere, to feel grounded in a world constantly in flux; it is a sanctuary that transcends the discrimination and violence of the outside world, a portal to joy.

It wasn’t until years after she moved to Denmark at 13 to escape the Somali Civil War that she came to understand the role of the artist (something not taught within her strict Muslim upbringing). At 17, she went to a museum with her aunt in Austria for the first time. She saw artists like Gustav Klimt and realised that she was not alone: there were others who, like her, saw the world through a lens of colours, ideas, and images.

From there, the artist made the pilgrimage, as many artists do, to New York, where she was introduced to contemporary artists, particularly the work of Black abstract artists like Mark Bradford, Sam Gilliam, and Stanley Whitney. “I loved seeing his work,” she says of the latter, “his very simple language of colour and understanding that art didn’t have to be so complicated: that’s how I approached painting.”

Her classrooms were galleries, her instructors the artists whose work animated the rooms. She picked up a paintbrush and never looked back. The walls she painted on as a child followed her to New York, reborn as murals. She painted in a garden behind Bellevue Hospital, where she volunteered (and where a wisteria tree she planted stills grows tall and fragrant) and where she met her friend Annatina Miescher, an art therapist who championed the painter and ushered her into the art world. She painted in notebooks after work, on rooftops, in a tiny studio, and then in a slightly bigger one. She painted her way through the city, selling artwork at Union Square and taking mural commissions before landing her first exhibition, aptly titled Solo Debut, at White Columns Gallery in 2015.

Eventually, she painted her way upstate, where she would take the bus that snaked down the Hudson River into the city. She showed her paintings in France; she showed at countless group shows; in 2019, she had her second and third solo shows at Fierman Gallery; an exhibition in Athens. Now, with her four solo exhibitions in New York and her first with Nicola Vassell, the artist’s star continues to rise.

Uman is a fully realised artist, a force of creativity powered by an unwavering work ethic. Did you make all of this in the last two years? I ask, amazed, trying to absorb the magnitude of what I am seeing. And not only is it a lot of work: it is all incredible. Yes, she nods, save for a few works that travelled with her. “Sometimes I don’t feel like I’ve done enough. I’m just starting. I haven’t made my best painting yet,” she says.

“I specifically don’t want my work to be negative and definitely not political. I don’t tell people my opinions on politics, and I’m just assuming everybody knows what I stand for just by knowing who I am, but I don’t make it a point,” says the artist.

At a time when identity is so often affixed to artists’ names, the first sentence offered in a life story, Uman is taking back the power of her narrative. She prefers to keep her artwork a safe space, a beacon of joy despite turbulent times, leaving conversation about politics and discrimination in the peripheral. She tells me that there are times when she feels alienated and even unsafe when she leaves her sanctuary on a hill and drives through parts of upstate New York where conservative values veer towards the far-right and the dangers of racism, sexism and discrimination become very real.

Here in the mountains, to be a Black trans woman in America can be as claustrophobic as it can be freeing. Up in the Catskills, she paints what she sees. “My work offers an escape. Whether it’s the night sky, the sun, or a cow in a field, I want it to feel good for the audience. And the first audience is me. I’ve always felt like if I was to make great art, it would have to come from deep within me and be very honest,” she says. “My work is its own activism, just painting my life, existing, living. I don’t need to say too much.”

Who is Uman? “Uman is my invention,” she says, tall with an easy smile and a deep stare, recalling how her name came to be. “It’s close to my birth name. In high school, I was super skinny and super tall, and I would walk around in heels and catwalk in the hallway. Everybody called me Iman, so I changed my name to Uman at 19 and legally changed it in my 20s and haven’t looked back.”

Uman has a prolific output, which is not only celebrated in her large studio but within several significant institutions. Not to mention, Uman certainly has art world friends, including artists whose work she collects: sculptures by Ambre Range Sibley, Cristine Brache, and Felix Beaudry seem at home in her Albany space. To reduce Uman to ‘an outsider’ would be greatly limiting, yet, the reputation prevails, a nod to the absence of formal training in Uman’s repertoire.

On this subject she notes “I’m in a weird fight with these gods, these intellectual art school insiders. I’m still an outsider, but I have reached a place where I’m in my own lane. I see myself as their colleague. We’re in the same world.” But the definition of outsider artist lingers; “I don’t think someone like me is allowed in that world.” Then she adds, “I just want to be accepted as a painter,” she emphasises, pausing, “actually, scratch that. I don’t want to be accepted. I’ve already accepted myself. I’m already in that world. Deal with me.”

I inspect a small self-portrait on her desk. “I took that picture in a sunflower field in the South of France and made it into my business card,” she tells me. “People thought it was funny; I was giving them a card with my picture just so they could remember me,” she laughs. “Everybody has documentation about their life, even the film photos. I don’t have a lot of baby pictures because of my migration.” The small number of photos she carried in her bag when she left Kenya were eventually lost to a flooded bedroom in Bedstuy, drenched by a sprinkler system that had put out a fire on the floor above her.

The years that followed were fast and glamorous, pre-camera-phone days immortalised in the painter’s memory: “I remember walking around New York City in the first few years that I was there, on Pride weekend. I was in the East Village going to meet up with my friends at around 2 in the morning, and a group of these French tourists thought I was a hooker. I was wearing short shorts, and I stood across the street from them; they were screaming and shouting at me from across the street, and then they started to take their cameras out, and I stood there, posing and feeling myself. I thought, I will never know what happens to these pictures,” she smiles. “That’s why when I moved upstate, and even years later, I decided I was going to do a lot of self-portraits to make up for those days.”

We stand facing a gallery wall of pictures behind her desk. “That’s my trail behind my house. This is my studio. That’s my house,” her elegant fingers glide from image to image. “Those are flowers that grow wild. These are everywhere in the summer,” she points to a photo of a large spotted toad, “I just saw his relatives. This is where I sit outside by the backdoor. That’s my bedroom”: pink glowing light cuts a square against the night sky. “That’s my studio door looking into my bedroom. Here is the view from my little paradise: those are the valleys. It’s incredible.”

As we weave through Uman’s studio, it becomes clear that, when pieced together, every object builds into a symphony of her life: self-portraits pulsing with memories near and far, with a crescendo, the artist says, that has yet to be heard.

Words by Meka Boyle