What separates a gallery from a clothes shop? Both are spaces where it is a pleasure to linger and look, after all. So why do they usually feel so separate, bastions of culture versus palaces of commerce? One littered with ‘do not touch’ signs, the other enticing you to touch and try on? Can a garment ever become a piece of art?

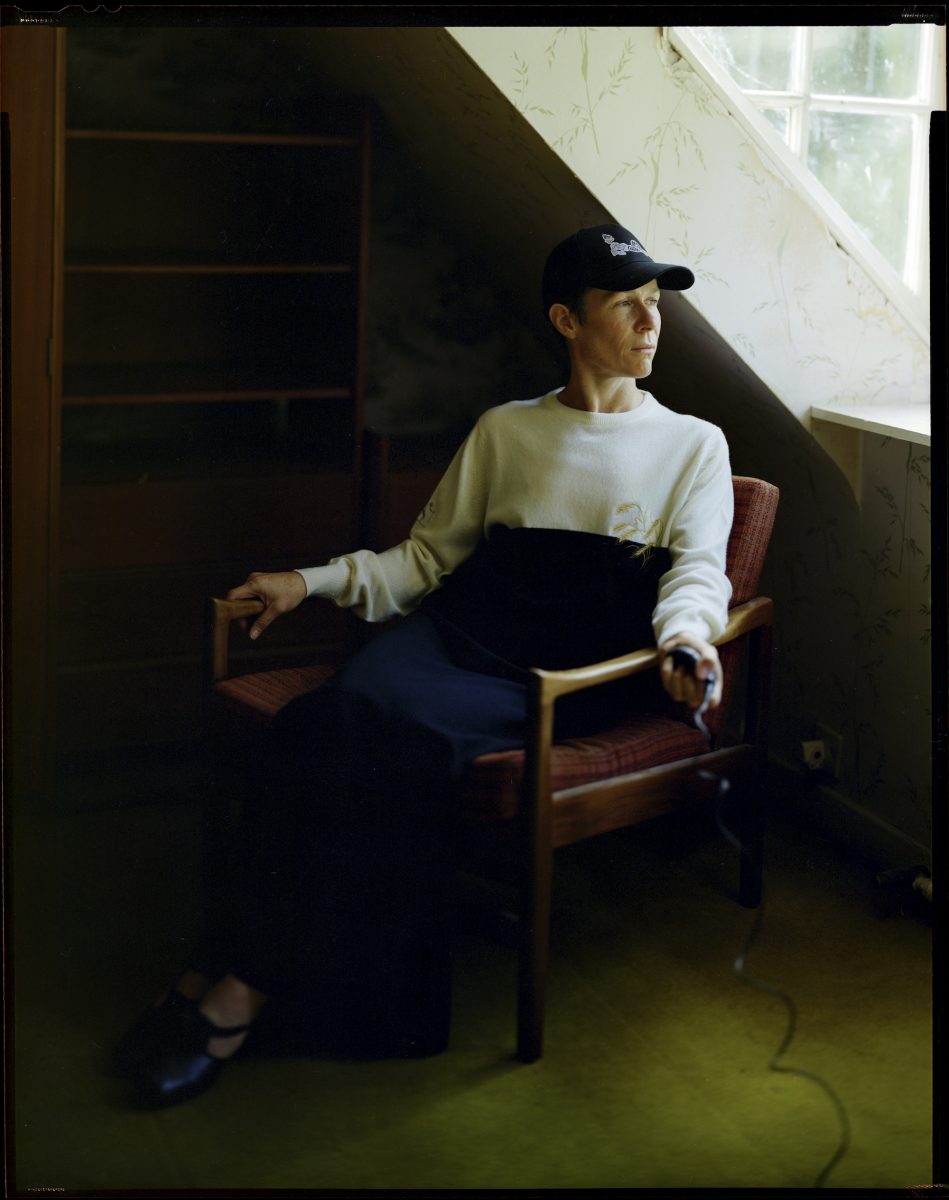

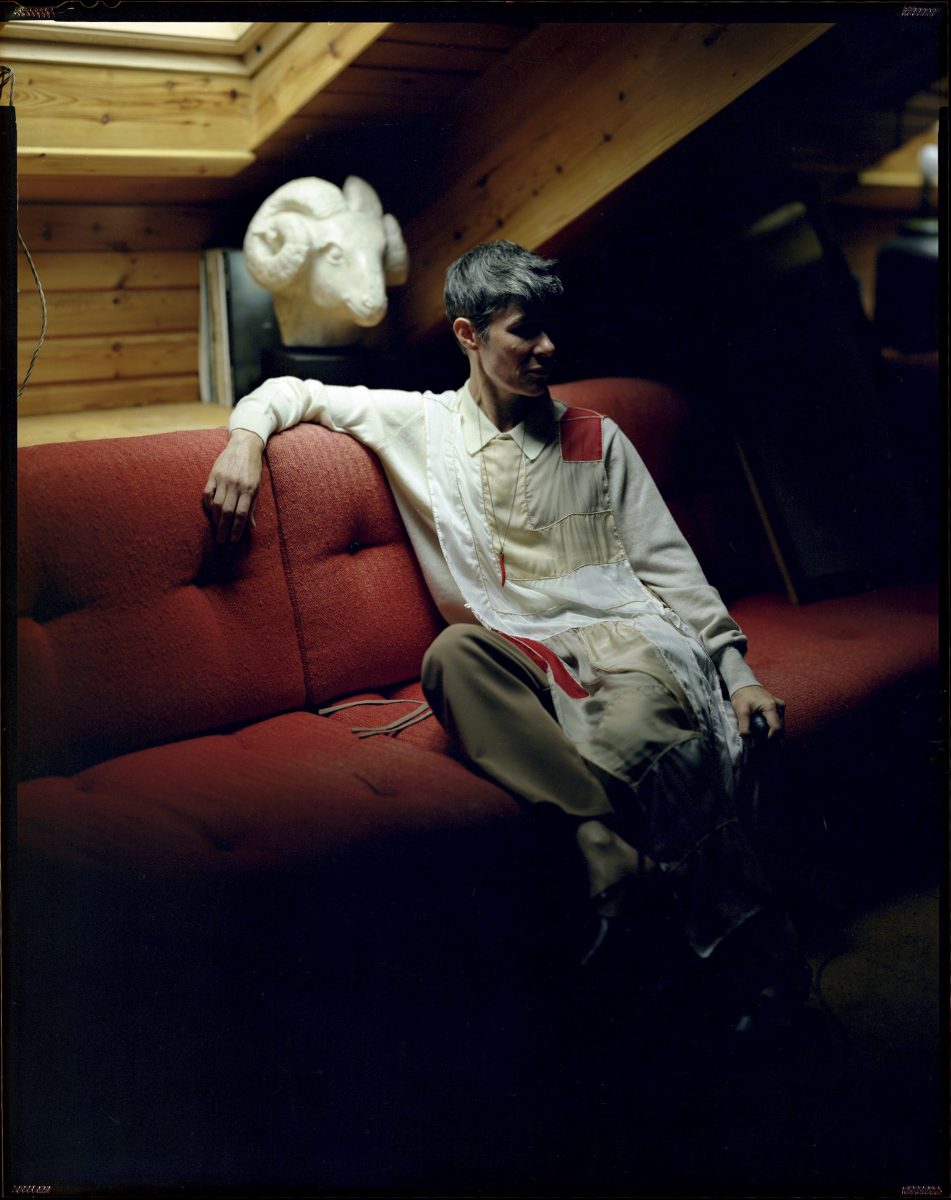

These concerns circle around clothing label Atelier EB. Founded in 2007 by artist Lucy McKenzie and her friend, designer Beca Lipscombe, they create intelligent, comfortable, irreverent designs. Their fashion collections, given names like Ost End Girls, Jasperwear and Dash People, draw inspiration from sources as diverse as Wedgewood pottery and defunct Soviet department stores.

Meanwhile, Atelier EB’s shows at the V&A Dundee, The Serpentine and Galeries Lafayette have allowed visitors to explore the exhibitions and installations, but then also buy the clothes featured for themselves.

There is an uncanniness to a place that refuses to differentiate between art exhibition and retail experience. On a trip to the Lucy McKenzie retrospective at Tate Liverpool, I found myself lingering in the back room. I had obediently wandered past the wall-size murals and kept behind the various white lines on the floor, but now I was among clothing.

“There is an uncanniness to a place that refuses to differentiate between art exhibition and retail experience”

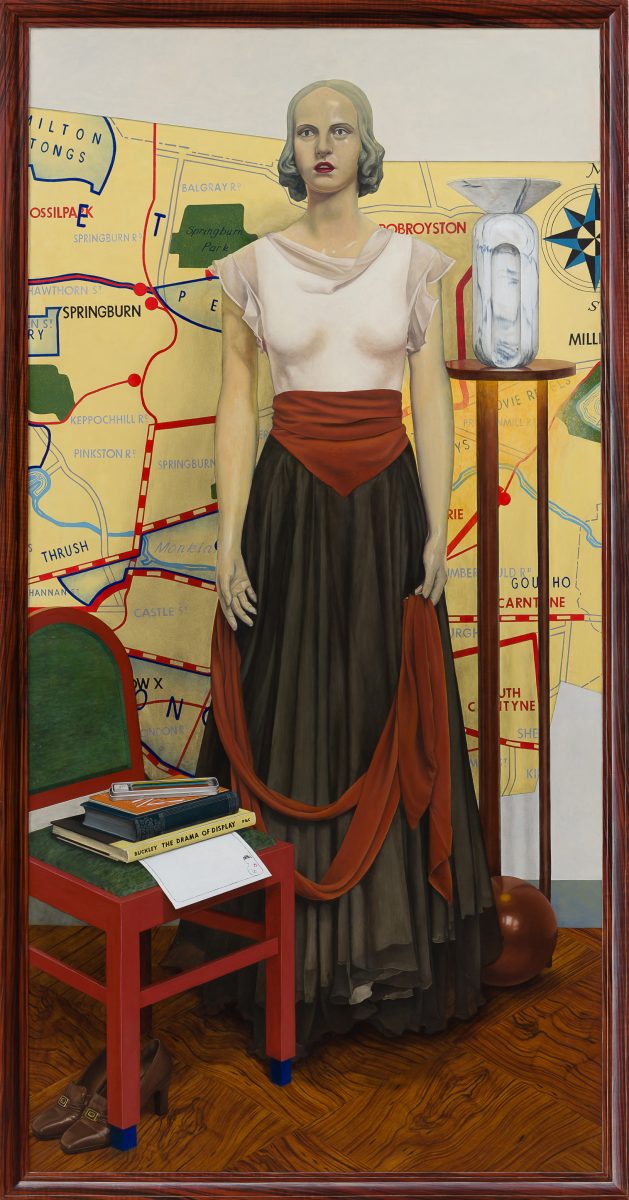

A trompe-l’oeil pinboard exhibited illustrated garments. A glass vitrine mocked up like a 1950s shop front featured bags and baseball caps suspended from wires while a skirt decorated with a stylised figure skiing over black fabric floated on a set of disembodied mannequin legs.

In the corner there was a mirror, a rail, and a wall text encouraging people to try things on. I tentatively pulled on a white cotton sweatshirt with an illustration of a boat. As I did, I half listened out for the steps of gallery security. My actions were not just sanctioned but encouraged, yet, in that moment, I still felt like I was transgressing.

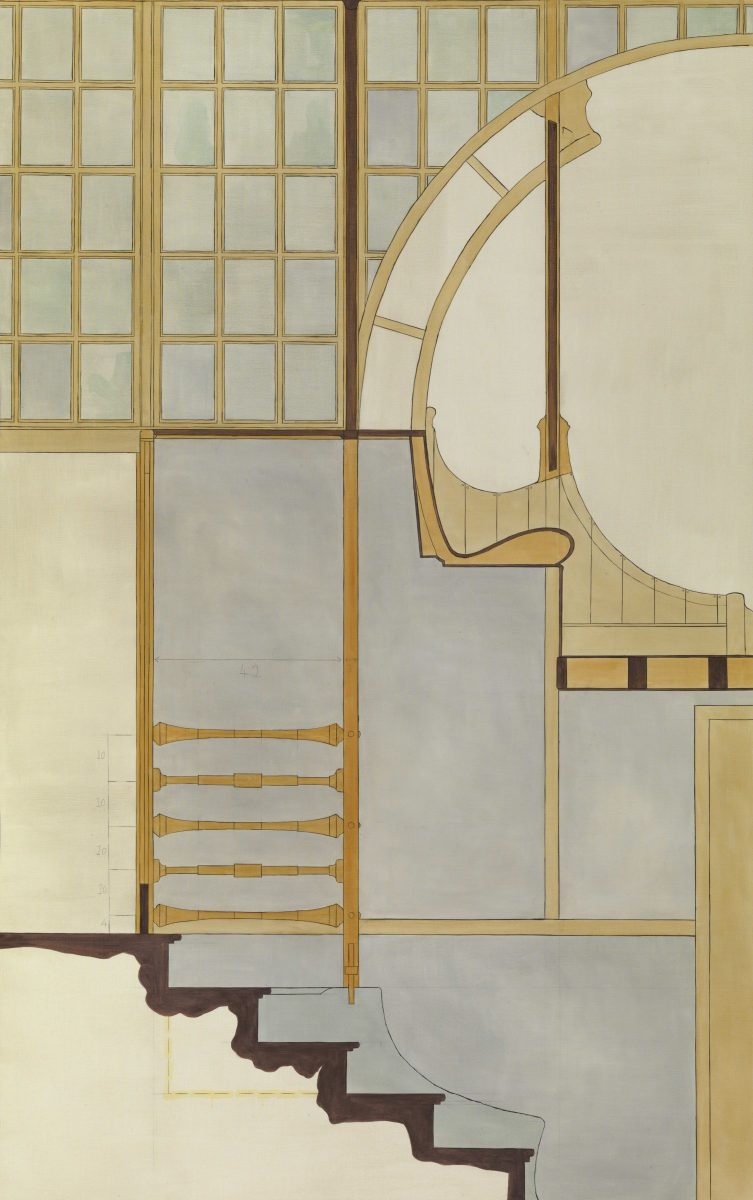

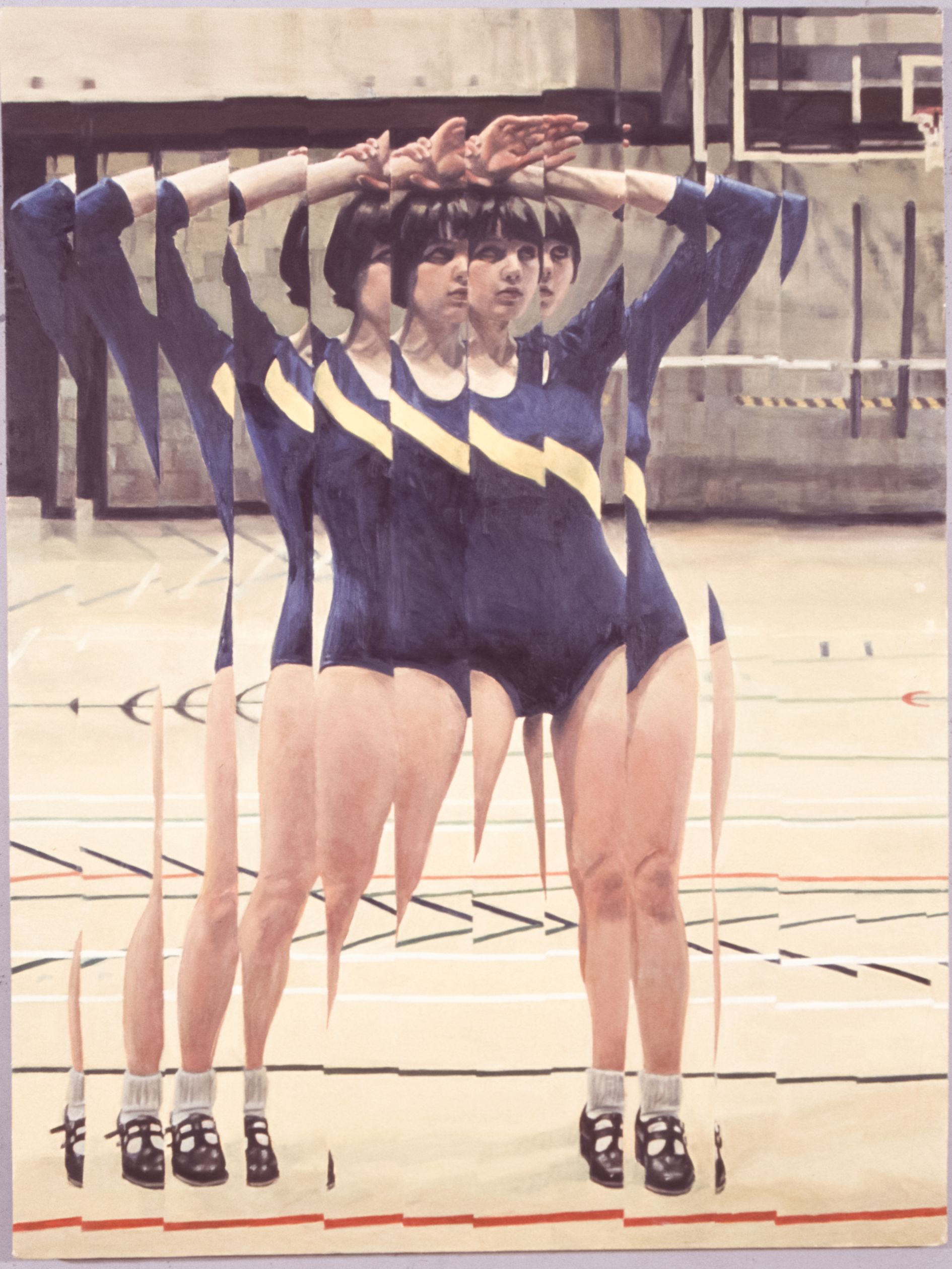

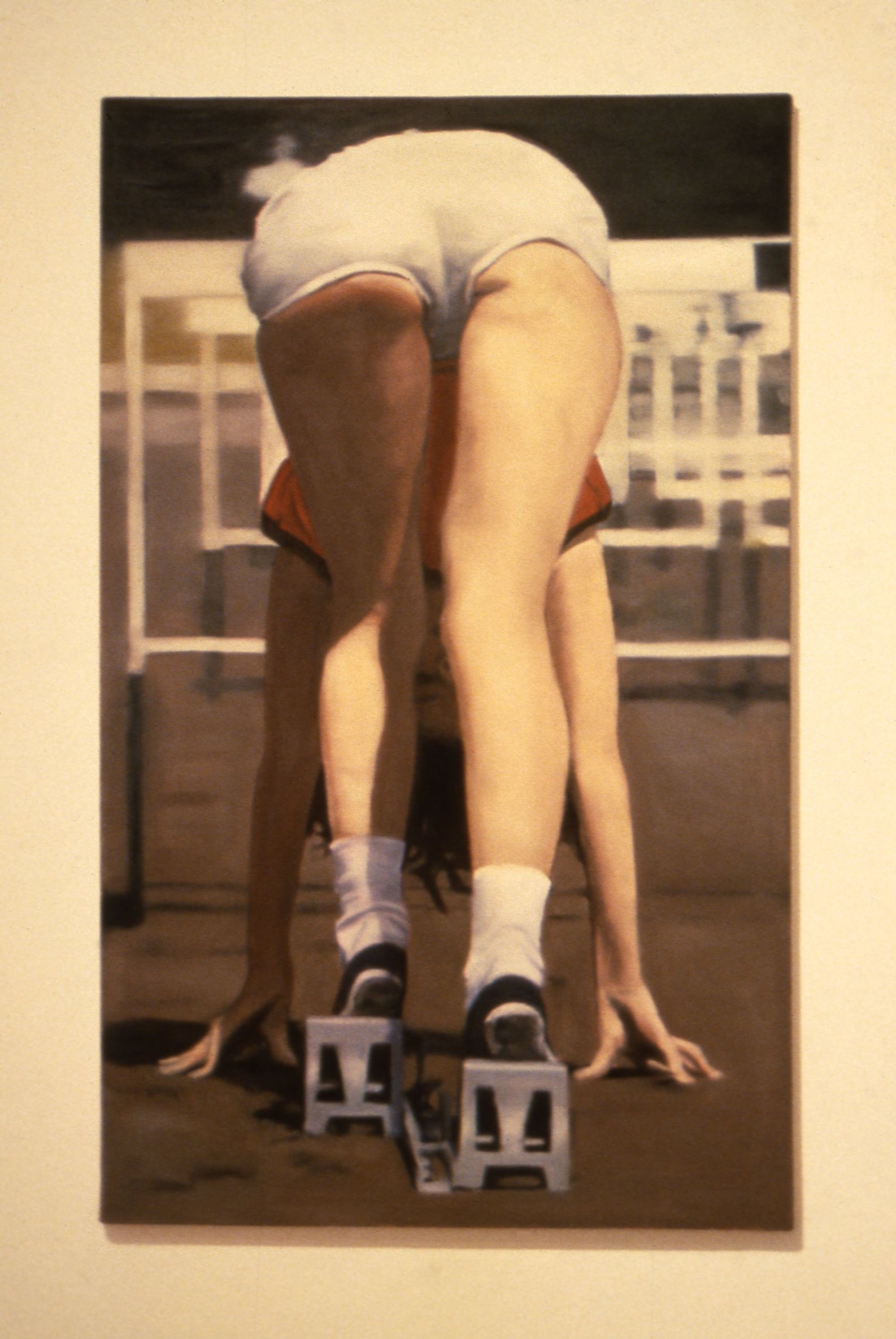

This shift from observer to participant is a flourish that feels distinctly Lucy McKenzie. The Glasgow-born, Brussels-based artist loves a perspective tilt. Whether she’s encouraging you to peer more closely at her uncannily realistic quodlibet paintings of notes and knitting patterns, or recreating photos of Russian gymnasts using her friends in costume, her work suggests a keen-eyed interest in porous boundaries.

“Collaborating on a fashion label is a complement to my practice as a visual artist, but it feeds it and loops in different ways I often can’t predict”

With Atelier EB, disrupting this boundary is entirely deliberate. “I wanted to see how showing fashion in museums and galleries could create a more interesting conversation,” McKenzie says. “In a way I want to create for the viewer something that is a kind of private fantasy of my own, the idea that you could see something staged in an exhibition, and you could buy that object for yourself, or even be invited to try it on in the space.”

The paths of art and fashion frequently cross. Fashion labels regularly cite artists as inspiration, meanwhile artists often explore the possibilities of clothing: creating textiles-based work; using garments as vessels for memory and identity; making use of costuming for performance art.

Designers whose work exists on the more experimental end of the style spectrum (Rei Kawakubo, Iris van Herpen, Alexander McQueen, Viktor & Rolf, Martin Margiela) have been labelled artists.

Countless artists, meanwhile, have collaborated with brands, from Yayoi Kusama bringing her trademark spots to Louis Vuitton, to Tracey Emin creating patchworked bags for Longchamp. Sometimes fashion even becomes a lucrative arm of an artist’s estate. Jean-Michel Basquiat has been leased out to an extraordinary number of brands including Coach, Converse, Mango, Supreme, Doc Marten, Wacko Maria and Saint Laurent.

But McKenzie’s decision to create clothing as a key component of her own artistic practice, making independent forays into the world of saleable, wearable goods, is surprisingly unique.

“What is fascinating about McKenzie’s work is how different it is from many other artists’ ideas of what it would mean to make garments or engage in fashion,” says Charlie Porter, fashion journalist and author of What Artists Wear. “Often it’s done in a super exploitative way: like luxury fashion, or purely for profit, purely for attention.” He sees Atelier EB’s output, though, as starting from a different point: “where it’s produced, how it’s produced, how the clothes are made”.

“I wanted to see how showing fashion in museums and galleries could create a more interesting conversation”

“It’s part of the pleasure for those that wear them,” Porter continues. “That sense of rigour with which they’re made, and the thinking and intention behind them, rather than just being a T-shirt with an image of an artist’s work printed on it.”

There is a long tradition of artists creating and selling clothing. In 1913 the Omega Workshops, run by Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, started producing furniture and textiles designs (a letter from Omega artist assistant Christine Nash detailed a delightful sounding “green, & yellow & black & white & khaki check dress” she was designing for fellow artist Nina Hamnett). At a similar time avant-garde queen of colour Sonia Delaunay began her own forays into dress design, combining dazzling fabrics with functional shapes. She later set up a fashion label called, simply, ‘Sonia’.

That lived experience can serve both artist and viewer. For artists, it creates new parameters for their work, bringing practical concerns about wearability and quality. For the wearer, they not only take away the experience of seeing their item participate in the artwork (becoming part of a wider commentary on the making of clothes and the act of shopping) but also now own a garment that will acquire an intimate life of its own when worn.

It’s also a useful way of making an artist’s work accessible. Plenty of younger artists produce clothes precisely because they appeal to a broader audience. From Charlotte Grocutt’s tongue-in-cheek scarves to Lindsey Mendick’s T-shirts, merchandise offers a different way to engage with their work, as well as a money-making opportunity.

When I tried on that soft, white Atelier EB sweatshirt, it was a quasi-talismanic sensation. Surrounded by artwork, it seemed to be part of a larger conversation, a window into McKenzie’s world of deceptive surfaces and beautiful objects. It made me think deeply about what I want from what I wear. What do I want it to say about me? How do I want it to make me feel? What associations and connections do my outfits invoke?

It’s a point of contemplation that McKenzie returns to. “When you make clothes, you are dealing with the fundamentals, the human body, and you are making something that can bring pleasure and comfort in a very direct way,” she adds. “Something that can be integrated into a life, imprinted with stories. I find this very rewarding.”

Rosalind Jana writes on fashion, art, culture, and travel. She has a column on photography and style for Magnum Photos