It’s early. I’m in Al Dhaid, thirty minutes east of Sharjah, UAE, deeper into the desert. I’m in one of the Sharjah Art Foundation’s cabs. It’s day two of SAF’s annual March Meeting, a series of panels and accompanying exhibition tours.

We park in front of an old hospital which has been repurposed for this exhibition. It’s a warm day. There are guards idling about. We look at each other with stoic seriousness. There are no greetings and no pleasantries. They feel, in a way, like the grounds crew of a cemetery. The air about them is respectful, but there’s a tinge of suspicion behind their eyes. Have I, an outsider, truly come here to mourn?

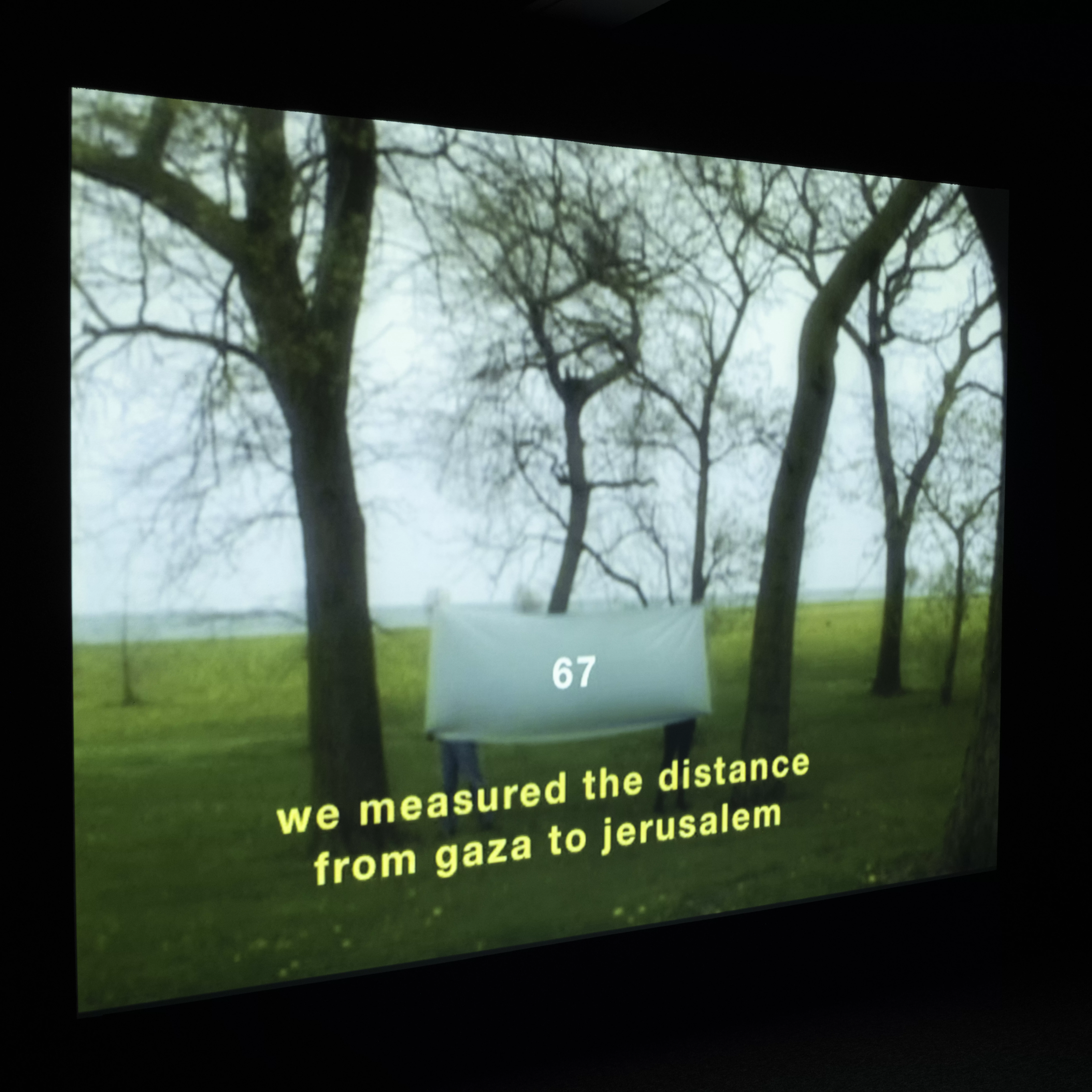

I walk with immediacy through the halls; I’d rather not waste time here. I search for something I saw the other night when I was here, a small, dark showing room (one of many a part of this exhibition), showing an old film. Finally, I discover it, recognizing the same scene I watched, the film by Basma Al Sharif, commissioned by SAF in 2009, We Began by Measuring Distance. Two figures in a forest, holding up what appears to be a bedsheet, which covers their bodies except their legs. There is a voice that narrates the image in Arabic. The English translation reads under the figures, “When we found ourselves empty handed / we measured the distance between Palestine and Israel,” the figures disappear from the forest, and he continues with accompanying subtitles, “And we found that Rome / was not built in a day.”

It’s sunset two days prior. After spending the day at Art Dubai, I take a cab deep into the desert of Sharjah. After struggling with my cab driver to find our destination, I meet up with the rest of the press group in the Al Madam “Ghost Town” Village in eastern Sharjah. Our SAF guides will give the group a tour of the village. The village was constructed in the mid-1970s but has since been abandoned by its inhabitants due to the harshness of the desert. The site is now a tourist pull and frequent photoshoot location. It’s believed jinns inhabit the town, remnants of its old inhabitants. It’s not difficult to feel why such a superstition exists—there is a presence, an air of life, that occupies these abandoned homes. There’s sadness. There’s joy. There’s a tethering, a pull.

As a part of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial last November, a travelling Concrete Tent, first constructed in Gaza in 2015, sits at the centre of the Ghost Town. As I walk between the structures of the Ghost Town and the Concrete Tent, I feel I am one of many who are creating footprints in the sand. I am one of many who have made a pilgrimage to this town, lost but not forgotten, not without new residents. The spirits of Gaza, all those who occupied the Concrete Tent, are here among the town’s original inhabitants. And they share one uncertainty: no one is sure whether the souls of those who were once here, in these structures, in the tent, are still among the living.

Earlier that day, more bad news from Gaza: over one hundred starving people were shot and killed by the IDF while attempting to receive food rations; it has been named “The Flour Massacre.” As we tourists gather in front of the tent, we are served Emirati tea, and we stand together. One of our guides tells us, “We must remember as we gather here in delight, among the living, that the spirit of those in Gaza are here with us, always—starving, occupied.”

We sit together in the tent, sipping tea, silently grinning at one another in solemn recognition. We are a part of a broader history of community—we exist where others once did.

Something catches my eye: Palestine. On the back of a black hoodie from a woman whom I don’t recognize. Draped around her shoulders, a keffiyeh. I turn to the PR rep next to me and ask who the woman is. “Hoor Al Qasimi.” The Sheikha of Sharjah—the daughter of the Sheikh— the Director of the Sharjah Art Foundation who oversees all programming.

Something hits me for the first time as I fade into the cushion I’m occupying on the ground of the Concrete Tent: this is the first time, in six months of watching the horror unfold in Gaza, that I am at an institutional art event where I am not only allowed to openly discuss my sadness about Palestine, but I am actually in mourning with my peers over the situation. And I am witness, for the first time ever, to a leader who openly supports the freedom of the Palestinians.

After we watch the sunset over the desert, we travel to the site of “In the Eyes of Our Present, We Hear Palestine,” the aforementioned retrospective of works from Palestinian artists staged at the hospital in Al Dhaid, where we’re rushed through in an effort to get our large band of visitors to dinner. The one exhibit that struck me the most: “Gaza Toys,” by Khalil Rabah, which featured eleven rubber toys of animals, lions, tigers, bears, encased in glass.

It’s 9pm, the following evening. It’s the end of the first day of panels at the SAF March Meeting. I realize over the course of day one how much emphasis has been allocated at this year’s meeting to discussion of the war on Gaza and the emerging concern that the occupied city was at risk of mass starvation. The air is extremely heavy with discussion of the Flour Massacre. Palestine is mentioned in every presentation. A community gardening group from Ramallah, “Sakiya,” delivers a speech which includes an acknowledgement that one of their program directors was recently imprisoned by the IDF. Poet Mosab Abu Toha, who escaped from Gaza with his family in November, joins us by video call from Egypt, where he is currently trapped, unable to receive a visa to join us in person.

I am overwhelmed with sadness and despair, as it feels many of us are. I fall asleep with my fellow Americans on cushions in the courtyard, still overwhelmed by jetlag. When I wake, tables have been arranged around the courtyard’s perimeter. I’m told I’ve been invited to a private dinner performance. Around forty of us take our seats at the tables surrounding the courtyard. At one end of the courtyard, there’s a single table in front of a screen that is projected to the top of the table. A little bit after we take our seats, a young woman in traditional Palestinian clothing, the artist and lawyer Shayma Hamad, slowly begins to walk the inner perimeter of the tables, taking her time to make eye contact and smile at every one of us. She arrives back at her table, sitting atop it is a bowl of rice grains.

Over the next two hours, she engages in two types of food performances: she tells us the story of her family in Palestine and the village food they cooked together for celebrations of mourning for lost ancestors. She also demands us, as five courses are served, to eat in remembrance of martyrs. One such demand, translated into English on the screen behind her as she spoke the entire performance in Arabic, was, “You have to eat, to be satisfied, and to ask Allah’s blessings for our deceased and martyrs for the land, which they left to us.”

As I eat the food, I think only of Gaza. I think of those killed attempting to get the flour that would be needed to create the village-style bread sprinkled with fenugreek. It is cold, bitter, and a little hard, but every bite feels like a life preserved. I let the wetness of my mouth soften it, preserving its presence, bearing witness to this food with my body in remembrance of those who died for the right to eat at all before the thought of enjoyment was even introduced to the act.

Afterward, we are served Maftool, a Palestinian chicken and rice dish. It is one of the most delicious things I have ever tasted. I am not sure if it is because of the food or because of the presence I had with it, but I will always remember it as one of the greatest culinary experiences I’ve ever had.

Over the course of the meal, she slowly spells out a sentence in Arabic using rice grains. Using my limited knowledge of the Arabic alphabet, I’m able to translate the words: “وزعت خبز عروحه”

I distributed the bread of the soul.

Written by Saam Niami