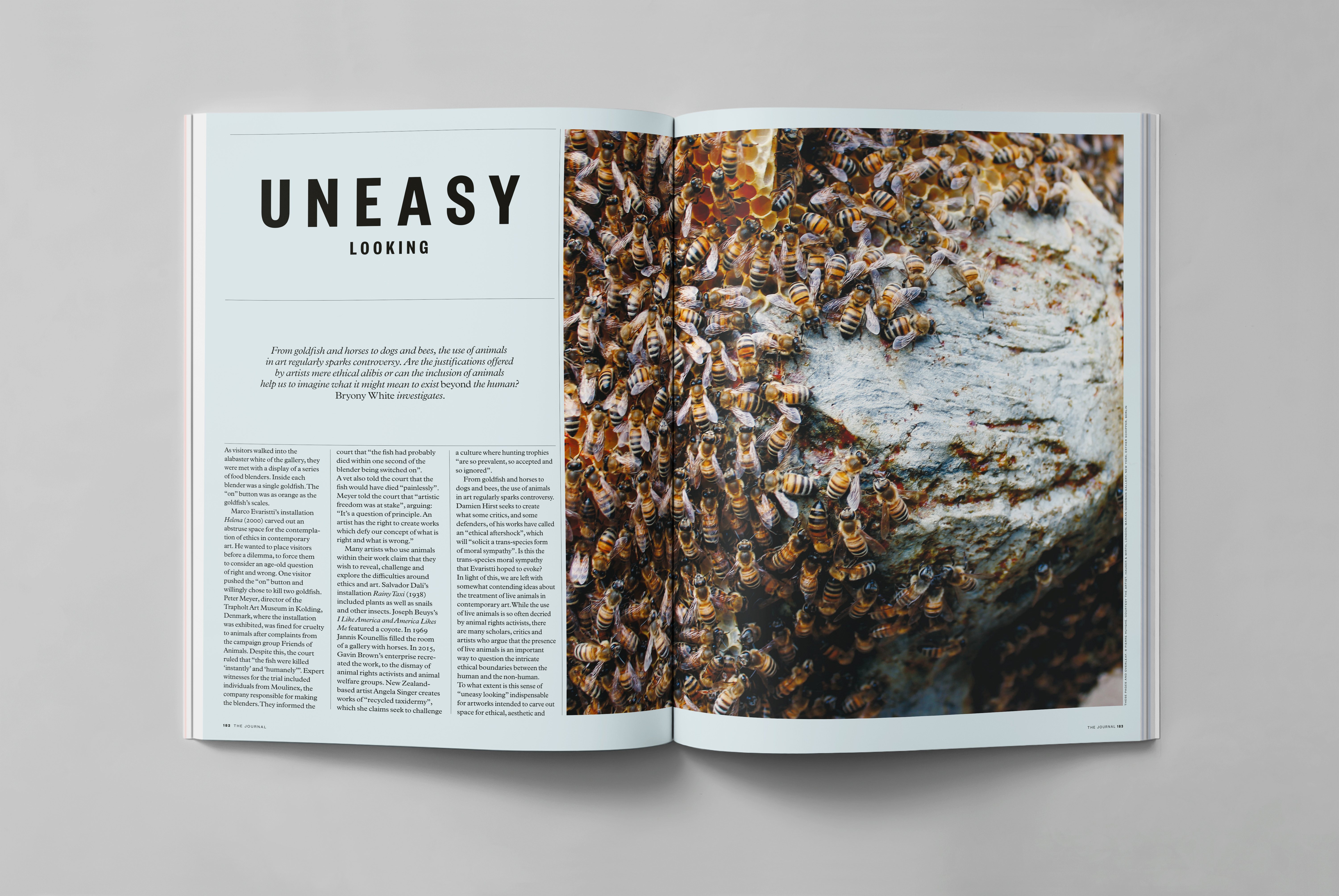

From goldfish and horses to dogs and bees, the use of animals in art regularly sparks controversy. Are the justifications offered by artists mere ethical alibis or can the inclusion of animals help us to imagine what it might mean to exist beyond the human? Bryony White investigates.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 29

As visitors walked into the alabaster white of the gallery, they were met with a display of a series of food blenders. Inside each blender was a single goldfish. The “on” button was as orange as the goldfish’s scales.

Marco Evaristti’s installation Helena (2000) carved out an abstruse space for the contemplation of ethics in contemporary art. He wanted to place visitors before a dilemma, to force them to consider an age-old question of right and wrong. One pushed the “on” button and willingly chose to kill two goldfish. Peter Meyer, director of the Trapholt Art Museum in Kolding, Denmark, where the installation was exhibited, was fined for cruelty to animals after complaints from the campaign group Friends of Animals. Despite this, the court ruled that “the fish were killed ‘instantly’ and ‘humanely’”. Expert witnesses for the trial included individuals from Moulinex, the company responsible for making the blenders. They informed the court that “the fish had probably died within one second of the blender being switched on”. A vet also told the court that the fish would have died “painlessly”. Meyer told the court that, “artistic freedom was at stake”, arguing: “It’s a question of principle. An artist has the right to create works which defy our concept of what is right and what is wrong.”

Many artists who use animals within their work claim that they wish to reveal, challenge and explore the difficulties around ethics and art. Salvador Dalí’s installation Rainy Taxi (1938) included plants as well as snails and other insects. Joseph Beuys’s I Like America and America Likes Me featured a coyote. In 1969 Jannis Kounellis filled the room of a gallery with horses. In 2015, Gavin Brown’s enterprise recreated the work, to the dismay of animal rights activists and animal welfare groups. New Zealand-based artist Angela Singer creates works of “recycled taxidermy”, which she claims seek to challenge a culture where hunting trophies “are so prevalent, so accepted and so ignored”.

From goldfish and horses to dogs and bees, the use of animals in art regularly sparks controversy. Damien Hirst seeks to create what some critics, and some defenders, of his works have called an “ethical aftershock”, which will “solicit a trans-species form of moral sympathy”. Is this the trans-species moral sympathy that Evaristti hoped to evoke? In light of this, we are left with somewhat contending ideas about the treatment of live animals in contemporary art. While the use of live animals is so often decried by animal rights activists, there are many scholars, critics and artists who argue that the presence of live animals is an important way to question the intricate ethical boundaries between the human and the non-human. To what extent is this sense of “uneasy looking” indispensable for artworks intended to carve out space for ethical, aesthetic and philosophical contemplation?

In June, I visited Tate’s new Switch House. The building was impressive and as I swarmed around the building alongside hundreds of others, I went into the “Performer and Participant” galleries. There was a long queue as I finally found myself in a room exhibiting one of Hélio Oiticica’s Penetrables. These structures are at the forefront of pioneering early installation art, but my attention was drawn to a small sign that read: “Due to high visitor numbers this weekend, the macaws have been temporarily returned to the owner.” The macaws had been removed on welfare grounds due to the sheer volume of visitors. PETA petitioned the installation, declaring: “animals are not exhibits.”

Another sign beside Oiticica’s installation read: “Both birds are from a specialist aviary in the United Kingdom that supplies birds to the media and television industries and for live events. They are trained and used to public display. The National Parrot Sanctuary and the UK Parrot Society have approved the living conditions of the birds in the installation and each has a veterinary certificate showing them to be in good health.” More information followed, as did a set of instructions, informing visitors that they were not to feed or touch the birds and remain at a respectful distance. By way of their exclusion, these parrots revealed a rupture in the processes of displaying historical works of art; the parrots were crucial to Oiticica’s original work and their removal presented fundamental challenges to presentation, documentation and conservation. The absence of the parrots also reminds us of the fragility of including animals within exhibitions: preservation isn’t just a term associated with museum conservation. It is a prescient reminder that an “aesthetic alibi” isn’t necessarily the bottom line and sometimes the well-being of live animals must supersede the artistic intention of the work.

As part of Documenta 12, Pierre Huyghe created the installation Untilled in a secluded area of Kassel’s main park. Within the installation Huyge displayed inanimate objects alongside artefacts (including remnants of work by artists like Joseph Beuys and Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster) and living organisms, plants, animals and bacteria. It was a pulsating, porous site that unfolded and transformed itself throughout the duration of its exhibition. An Ibizan hound and Huyghe’s collaborator, Human, roamed the liminal eco-system of Untilled, helping Huyghe ask foundational questions about the permeable boundaries between nature and culture. Human existed in Untilled, supposedly living autonomously within the evolving ecosystem that Huyghe had created. According to one critic, visitors to the installation took little notice of Human’s presence because Human didn’t appear to be suffering—he was not a blended goldfish. When the installation was displayed at LACMA, visitors were informed that Human “had been a rescue dog” and “is an accomplished performer having appeared in both France and Germany; had been examined by animal welfare organisations and a permit obtained for her inclusion in the exhibition”. Visitors were sold on the notion that Human was living a better life now. Many artists use this moral caveat to legitimize their work—ordinarily these animals would face the slaughterhouse or a life in a shelter. The cruelty that these animals have been saved from often becomes the underlying ethical bedrock for using animals in contemporary art, but does this outweigh the moral downsides of using animals in a gallery context?

In 2011 at Art Basel Miami, Miru Kim lived for 104 hours alongside a drove of pigs. She slept and ate alongside them, her naked flesh blending with theirs. Kim lived and rolled around in the dirt, lying next to the pigs and eating with them during mealtimes. According to Kim, “They will lead a very happy life and are already better off than when we found them.” But after the exhibition? Kim said: “We are looking to place them as pets with a family or at a community farm.” Kim and the pigs become part of the same unfolding eco-system whereby her communal living situation seeks to subvert the traditional hierarchies of man and beast, as well as the apparent destiny of these farm animals. Her presence in the glass pigpen is a process of unframing: her proximity to these pigs ruptures the established and often anthropocentric relationship between animals and humans.

We cannot simply argue that the inclusion of animals in contemporary art is always morally wrong. To consider it as fundamentally wrong in many ways reinforces an anthropocentric dominance inherent to the established essentialist structures that currently define the boundaries between animals and humans. If carried out in the right way, the presence and inclusion of animals can help to decentre this anthropocentric dominance and allow us to question the salient, essentialist lines between animals and humans, which in turn allows us to extend our understanding of stable embodied human and non-human existences. Lying next to the body of a pig, the “human” body can become a prosthesis, a malleable skein of flesh that we can perhaps learn how to manipulate and control in new and alternative ways: the inclusion of animals allows us to consider what it might mean to exist beyond the human.

Despite this, sometimes it is precisely because we are human that we can justify using animals for the meta-ethical value of art—it is the anthropocentric privilege of being human that allows us to decide what is right and what is wrong: we ventriloquize human concerns and preoccupations. Pushing the boundaries of the nature/culture divide is undeniably important, but one can’t help but wonder: what do these animals make of their participation within the artworks of Hirst, Huyghe, Kim and others? In the 1970s Gino De Dominicis organized an exhibition that only animals could attend. We will never know what was in the show: De Dominicis succeeded in subverting the anthropocentric gaze of the art world. So often, it is clear that humans have the privilege of using animals to represent and portray their ethical, philosophical and aesthetic dilemmas. But as Massimiliano Gioni rightly argues: “unfortunately, we will never know how animals depict and imagine us.”