Divine Southgate-Smith’s artistic practice uses archival poetics and material memory to reimagine how we record, remember, and relate to time. They spoke to Elephant’s Alma Feigis about the emotional weight of the archive, the enduring artistry of Nina Simone, and the power of uncertainty, play, and ancestral knowledge to transform how we engage with the past.

Divine Southgate-Smith’s studio is flooded by the warm light of early spring, their desk surrounded by shelves of objects—a personal archive of relics from their life and work. Delicate ceramic pots, handmade and gifted by a close friend, sit among a wooden Mancala board, a small hourglass, and hardcover books spanning subjects from Frantz Fanon to Sun Ra. It’s a fitting selection for the Togolese-British artist, whose transdisciplinary practice draws from literature, music, imagination and community as sources of inspiration. Their work invites reflection on the future while remaining in continuous dialogue with the past—a dynamic made possible by their deep engagement with archival material.

Navigator, the artist’s first solo exhibition at Nicoletti Contemporary, marked an important point in their evolving exploration of time, memory, and archival poetics. In the exhibition text that they wrote, Divine explicitly, quite publicly, questions their journey and all that’s yet to come: Where am I going? What will I do this time when I feel like I have nothing to say? But they do not necessarily attempt to answer these questions. Instead, they allow uncertainty to linger, dissolving the urgency for a singular response. The more Divine engages with institutional archives—they are currently leading a series of creative workshops with Manchester Museum and were recently commissioned by the Sainsbury Centre—the more they ask themselves how to channel uncertainty and incompletion in ways that give space to not only fear, but creativity, hope, and speculation. “Often I’m asked to come in as someone who can reimagine,” they say. “There’s a lot of information that is unknown in the archive. I’m essentially entering the space with this understanding, and I think by doing that, I naturally look at uncertainty as possibility.”

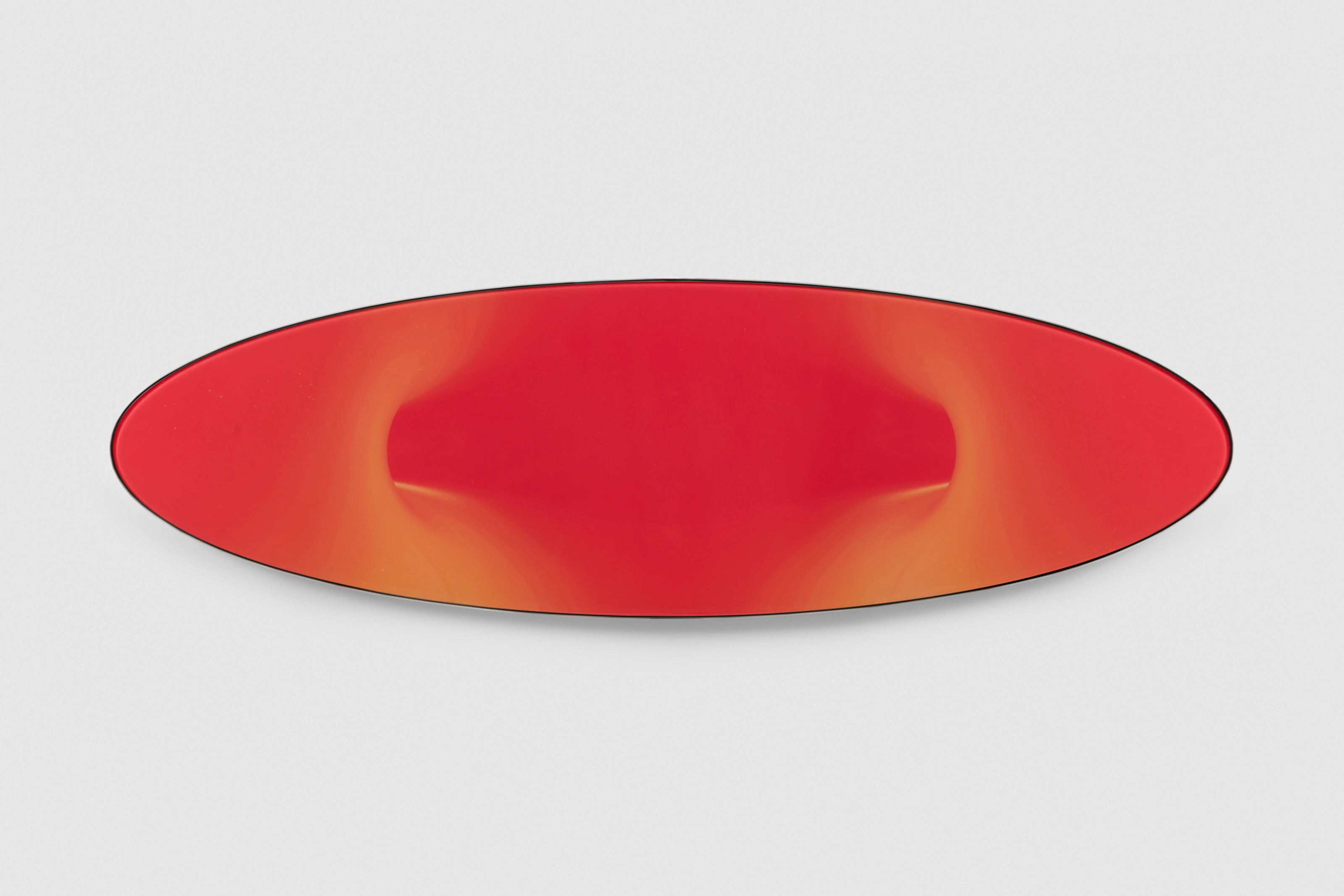

The body of work in Navigator, which Divine described as an exploration of the movement and refraction of ideas and energies through time, emerged from a period of reflection on their recent months of both intensive archival research and simple existence. The overwhelming state of the world has made uncertainty not only a theme within their artistic practice but also an unsettling force in their sense of belonging and agency. “Essentially, you’re being confronted with a system of knowledge that’s deeply embedded in the way you perceive yourself,” Divine explains. “There was a moment when I started to feel the weight of dealing with this kind of memory.” Alongside long hours spent making playlists—they curate one for each exhibition—transforming the archive and renegotiating what archival practice means has become a form of self-care for the artist.

While play and imagination aren’t generally thought of in the context of working with archival material—the term evokes dusty shelves lined with rows of cardboard record boxes and serious, ink-blotted catalogues—Divine sees archiving as something more than these seemingly rigid, historically-bound spaces, though it’s precisely this quality that drew them to the archive as the site of their practice. “Because it is so data-driven, so fixed, there is this feeling that you can’t manipulate the archive, though the whole thing is a manipulation.” Rather than conforming to its staunchness, Divine embraces the poetics latent in archival material and sees poetry—a form which, they maintain, “blends imagination with memory”—as a way of archiving itself.

Early in their exploration of archiving, Divine created work inspired by Jamaica Kincaid. “She’s the most poetic archivist I know,” they say. “She writes about the relationships between the people around her, between her parents, her mother, her husband. The way she writes it is like magic realism, but she’s essentially archiving her life.” By using poetry as a means of introducing play into archives and museums—institutions typically resistant to uncertainty and transformation—Divine explores other ways of engaging with archival material. “Unlike the archive, play has no agenda,” they explain. “Introducing play into that space is powerful, because play is one of the few things in our human experience where uncertainty is rewarded.” In this context, uncertainty becomes expansive and hopeful. Gaps become spaces for speculation.

Though their process often begins in the institutional archive, Divine has gradually shifted toward alternate temporal structures and non-linear ways of knowing. While time is often understood as a linear progression in the West—“The dominant idea is that we’re always moving forward, that there’s no room for return,” they explain—the past holds equal, if not greater, importance than the future in many African societies. “Things come back, but they return in a new context, in a new configuration. Meaning shifts. The fixedness of the institutional archive becomes obsolete.”

Divine is interested in two ways of recording: how African communities historically represented themselves, and how they appear in the colonial archive. The contrast between these archival practices, Divine proposes, reveals a deeper divergence in the function of the archive itself. Non-Western bodies are primarily held by the institution through ethnographic photographs that continue to denude the humanity of their subjects and fix them in a static, extractive temporality that severs rather than sustains connection to the past.

Within African traditions, however, the memory of these people takes shape in material forms, like clay and wood. “These objects don’t only commemorate,” Divine explains. “They mediate presence between worlds, between the material and the immaterial planes, across generations.” While traditional archiving is often about preservation—to protect objects from decay and damage that time effects—these sculptures’ value lies not in their form, but in their spiritual function: “They communicate with the past and with ancestors. They’re meant to be touched, used, engaged with. Already, that sense of archiving is completely different; it holds a different relationship to time.” While colonial photographic archives often imposes a linear chronology, here, archiving invites a cyclical experience of time which sustains ancestral continuity. Divine’s understanding of the archive as a temporal instrument raises the questions: What other ways exist to mark time? What other ways are there to record and remember experiences on Earth?

Catching the morning sun during Navigator were three woven collages, their edges worn, their surfaces embossed with odd floral shapes and printed with a blur of magenta shapes—like the eyelids’ memory of light once closed, or faint moments of a dream drained onto where the head lay. In Relics of a Dream Unfolding (2025), decontextualised, abstracted fragments from archive documents are UV printed onto tatami mats similar in texture to those Divine slept on as a child in Togo. The work, however, isn’t just about what is being depicted; for the artist, “materials hold memory—sometimes directly.” Rather than the intimate and recognisable straw of their original form, the mat is rendered in plastic—an unfamiliar material suited to a Western landscape. Relics of a Dream Unfolding is an ode to home, steeped in sentimentality and warmth, as well as a sensitive reflection on the legacies of colonialism and extraction embedded in a material.

Though the series began as an experiment, the artist has received deeply emotional responses from visitors. “It’s been quite surprising and beautiful to see,” Divine says. These reactions attest to the work’s ability to reveal a repressed, child-like longing to record, remember, and make sense of one’s dreams. “That ties into my thinking about memory,” they add. “It’s so slippery and evasive—but that’s what makes it one of the most liberating aspects of our lived experience.” The artist has been looking into the parts of the brain where memory and imagination are held—and as it turns out, they occupy the same space. “It makes perfect sense that, in order for us to remember, we have to imagine. That’s the way I want to approach archiving within my practice.”

Divine also wanted to capture the memories and dreams of the individuals in the images they engage with—dimensions often stifled by the institutional archive. When looking at these photographs, they imagine what occurred beyond the frame: “The person moves on. They go home, they’re with their family, they have dreams and aspirations. This piece is an attempt to recapture those dreams in this material that is politically charged, but also has a gesture in it that’s quite innocent.” The resulting compositions carry a depth and texture that recall a spectral presence. These figures, long confined to the archive, remain subtle and withheld. Their agency is restored, not through traditional representation but the refusal to render them undignified—yet even in their abstraction, they remain insistently there. A ghost never dies, Derrida wrote—it returns to inhabit the spaces between existence and absence. The colonial traumas of its past persist into the present and will inevitably, inexorably continue into the future. Haunting, in this sense, becomes a means of unsettling linear understandings of time and opposing dominant historical narratives that use the past to justify the inequalities of the present. Divine invites us not to resolve these spectres, but to recognise and stay with them.

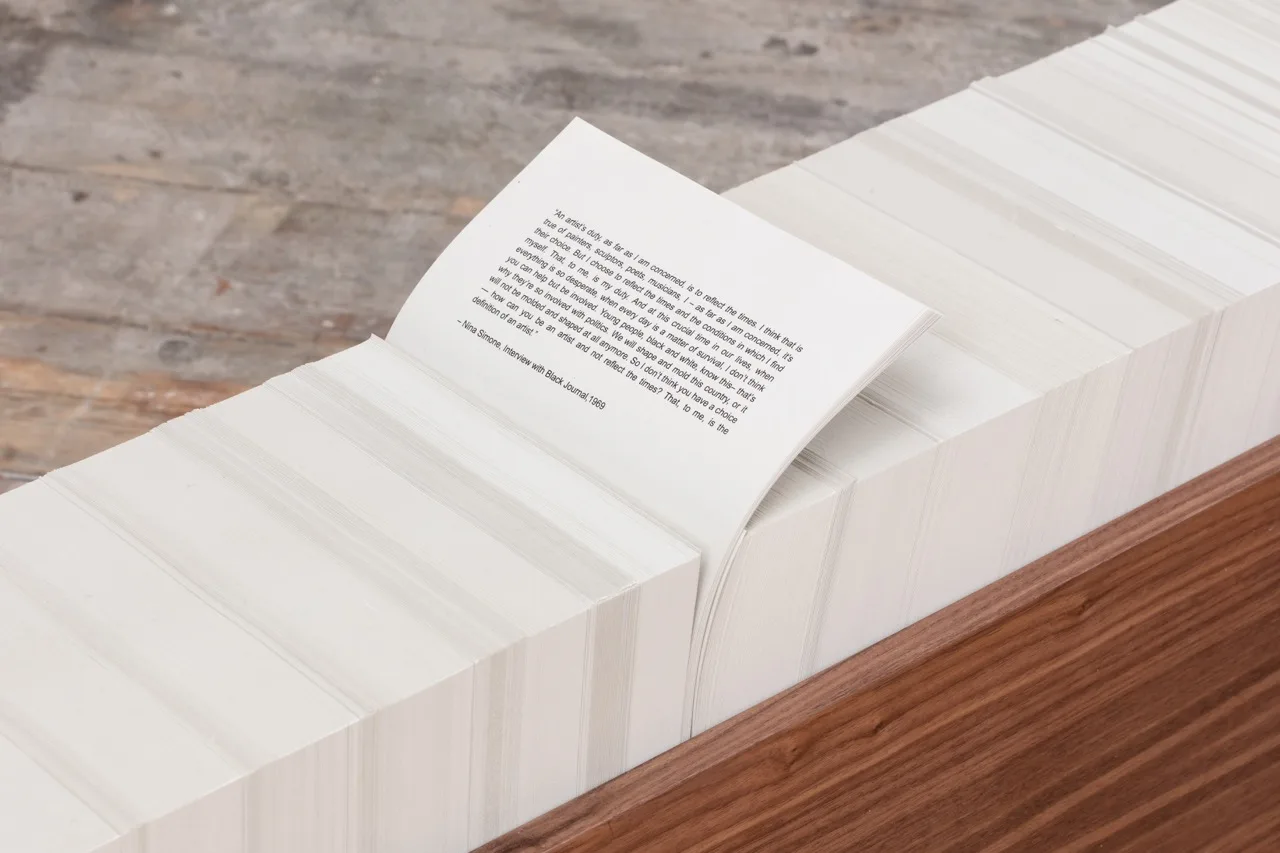

Faced with the tension between engaging with past collective memory or present introspection, Divine conceives the act of remembering as something situational and ever-shifting: “Imagine an infinite tunnel where all of time is compressed. You can choose one fragment, or one string, that might take you into the past or a vision of the future.” The Weight Of Remembering (2025), a 150-centimetre-long walnut box placed in the centre of the gallery space, is a materialisation of this tunnel through sculpture. The density of the piece, packed with A4 sheets of paper, seemed to exert its own gravitational pull, its sheer volume inducing an overwhelming sense of desperation—a reminder of the expansiveness of knowledge that exists as a potential to be mourned and learned from, yet how little ever is. “It felt important to give this abstract information a form,” Divine says. “In doing that, we’re reminded of our responsibility to remember.”

Unabashedly poking out of the row of papers is an excerpt from an interview given by Nina Simone in 1969. She is a figure that Divine finds themselves returning to throughout their work: “Even though we know her as a musician, her impact and understanding of artistry go far beyond that.” Divine first listened to Nina Simone as a child on a worn-out cassette compilation of Black musicians, though the language barrier meant that they couldn’t understand the words. They admit, embarrassed, that they and their little sister initially thought Simone was a man. “It was the authority of that voice that confused me about who this person was,” Divine explains. “But it was also what held me.” For Simone, documentation and reflection were not only an artist’s duty; they were intrinsic to her work. Her music captured and emotionally reinterpreted the events of her time, and in that sense, Divine sees her as an archivist. “In the art world, there’s often this idea that it can be an escape, a kind of removal from the world,” they say. “But she believed art is of the world.”

While Divine realises the responsibility of traversing this tunnel and selecting which fragments of history to represent in their work, the image is equally liberating: “You realise every moment you select has the same weight.” The thought is comforting. It dissolves the illusion of linearity and relinquishes the idea that things are fixed—rather, they “weave, bend, twist into one another” in ways that aren’t always expected. Now, Divine is presenting work from their series Aspects of Things Existing (2024)—first exhibited at their solo booth at Frieze London last year—in Handful of Dust, a group exhibition at Palmer Gallery, London, which positions sand as both a material and a metaphor that speaks to the transient, granular nature of memory and time. For both this series and Navigator, the tragedy and turbulence of events happening around the world required Divine to stretch time in both directions: to simultaneously project forwards with urgency and turn inwards and backwards with care. “Sometimes I choose to focus on the past, but even then, time doesn’t stand still,” they say. “I might be looking backwards, but I’m still moving forwards.”

Written by Alma Feigis