Over the last year, I have found myself often returning to Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Dressing to Go Out/Undressing to Go In (1973). The piece consists of 95 black and white photographs of Ukeles engaged in the endless routine of dressing her two young children to go outside and the subsequent scramble to de-layer as they discard clothes all over the floor. She described the work as “maintenance art”: an effort to make visible the domestic labour of childcare and the often monotonous, time-consuming rituals parents engage in to keep their children going.

In photography, the subject of parenthood is still underrepresented. By the nature of the job, photographers often spend long periods of their time travelling. In a pandemic, though, stuck at home, many photographers turned their lenses on their own families, and the complexities of family life. What has emerged is entirely different to traditional family snapshots. While new representations from different kinds of artists and photographers are welcome, turning those closest to you into subjects and collaborators often also comes at a price.

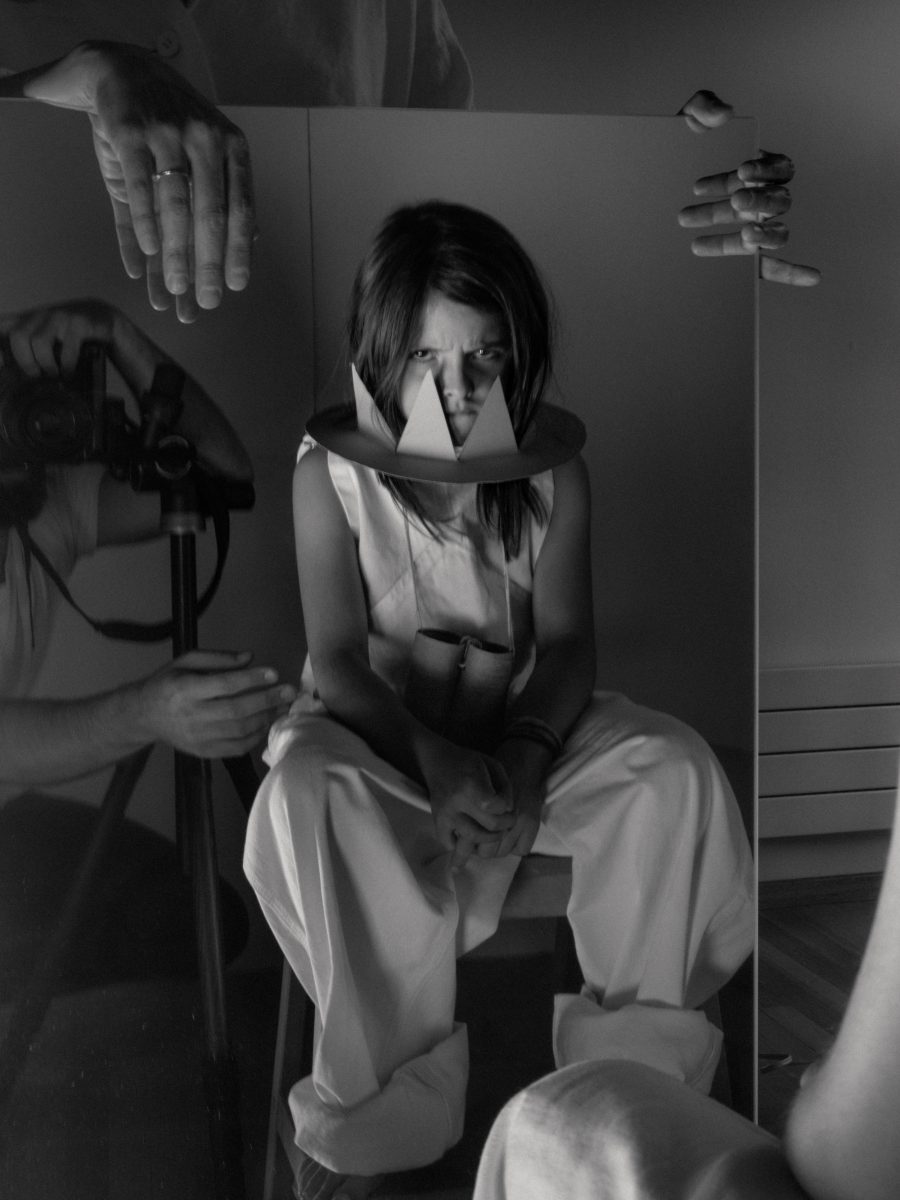

Mark Mahaney had one job after another cancelled as the pandemic hit, causing anxiety and uncertainty. But it offered a space to be involved in his family life in a way he had “never really experienced” before. The Wooden House is a whimsical series of domestic portraits Mahaney made with his eight-year-old daughter Veda. Born out of a commercial pitch that never manifested, the pair worked on ideas together as a way for Veda to learn about photography and for Mahaney to experiment as time stood still.

“Many turned their lenses on their own families but turning those closest to you into subjects often comes at a price”

The California-based photographer is known for cinematic long-form storytelling, grounded in place and explored through real-world observations. What is so refreshing about these photographs is how they describe the messy, conflicting emotions of parenthood, and how intimacy in a family structure is in constant flux. Unlike his usual work, the process of making is laid bare speaking to the ever-evolving nature of the father-daughter bond.

- Both: Mark Mahaney, The Wooden House, 2021. Courtesy the artist

“There was a playfulness at first,” Mahaney explains. “Before we knew it, we had five or six images that we both really liked. We had fun, but it definitely came with drama and tears. It eventually devolved into these genuine moments of tension, not just between Veda and me, but also with my wife as she could see Veda’s conflict in not wanting to disappoint me.”

In Gravity Begins at Home, social worker and photographer Guy Bolongaro captures the way children play with performativity as a means of self-discovery. His two children, nine-year-old Rudy, and four-year-old Ivor, often pictured in their London home, are the subjects of the work. The viewer feels their emotional energy, their desire to be nurtured, all animated by flash to draw our focus on the small gestures and expressions that often go unseen when they unfold in real time.

The work is unsentimental and ambiguous about parenting, yet strangely evocative in the charming way they embrace the weird, unpredictable chaos of family life. “Lockdown has been tough, and our circumstances are not ideal by any stretch, so I’ve been trying to capture the chaos and vitality of family life to reinforce the fact that we are ok, that family can work,” Bolongaro says. His ability to animate the multifaceted nature of the parental bond, from caregiver to co-conspirator in imaginary play, feels unexpected and refreshing. The project (to be published by Here Press) also forced Bolongaro to reflect on the the ethics of making work involving immediate family. “I’ve had to reflect on questions of objectification or the possibility that my photographic compulsion can become a problem both in terms of making the kids self-conscious and making me absent from the group dynamic,” he explains.

“These photographs describe the messy, conflicting emotions of parenthood, and how intimacy in a family structure is in constant flux”

- Both: Guy Bolongaro, 2020. Courtesy the artist

New parents have had their own unique circumstances to navigate during the pandemic, from restrictions in the delivery room to a sense of isolation in the early months of parenthood without home visits or support. “I doubt I would have made this work had we not been in a pandemic,” says Rose Marie Cromwell of the series she made after the birth of her daughter Simone in December 2019. “It gave me time to really sit and consider all that was happening internally and externally.”

The work Cromwell made is now published as a book, Eclipse. It contemplates the life force demanded by birth and early motherhood from an intensely personal perspective. “This work has helped me process what it has meant to become a mother at such an isolating time,” Cromwell says. “It has also helped me to connect to my daughter while still making work and being creative.”

Eclipse charts the transformation Cromwell underwent in becoming a mother, blending documentary moments with dreamlike scenes, and moving from physical labour to emotional transcendence. The images move between the constructed and the natural: a vest stained by leaking breast milk dries in the sun; her daughter Simone levitates between the palm trees; an exhausted Cromwell gets a haircut from a friend outside while breastfeeding.

Photographing her own family has also given Cromwell time to consider the way she shoots other subjects: “I have tried to examine why I make the work I make more deeply. I have asked so many people to be vulnerable in front of my camera that it felt only fair that I finally am vulnerable in front of my own lens.”

In contemporary visual culture, parenthood is often reduced to tired tropes, homogenous aesthetics and the perpetuation of age-old myths. The pandemic has promoted a new way of seeing parenting and forged a new way for photographers and artists to understand themselves and their families. Unlike the pictures in a traditional family photo album, these photographers prove that it’s not only the happy moments and monumental occasions that are worth preserving; and it’s not only parents who might find something of themselves in these pictures.