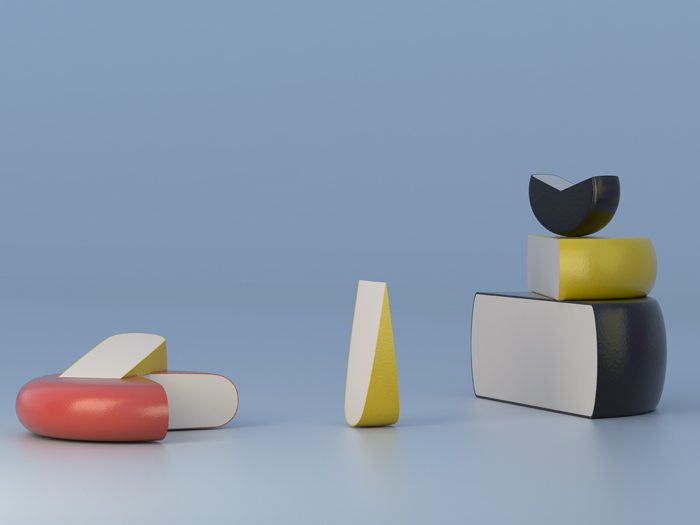

They were, perhaps, the most unusual pictures of cheese I’d ever seen. Hanging on the wall of the Manchester Art Gallery, the cheeses, stacked in an imperious, colourful pile, seemed to know something I didn’t. Geometric chunks, with a plastic flatness to them; they looked edible but dangerous to sink your teeth into.

writes later in an email to explain this predilection for uncanny lactose. ‘I often do things a bit back to front, taking a long time to understand why a particular thing registered interest for me in the first place. I’d made those objects on the computer back in 2010 and there they sat. It was only after looking at the work of Georg Flegel, the 16th century still life painter, that it struck me that what I was interested in was the permutations of one form, and that this work was kind of like process-driven minimalism. Then it became important to make something that had some of the logic of cheese, but clearly wasn’t cheese. (A wax rind, a curved cylindrical shape, the colour palette.)’

Flynn’s process laboriously uses 3D software to sculpt objects into resulting photographs and films–which explains their phantasmagical presence, alluding to the rich–oftentimes gruesome–allegories they release if you tap into them. One of those works is Bucket, (2011), another piece on show at Manchester Art Gallery.

‘The starting point for this piece was William Hogarth’s The Four Stages of Cruelty, the final etching in that series is The Reward of Cruelty, where Hogarth’s main character in the series of works, Nero, lays dead on a surgeon’s table dissected with his intestines hanging out of him part gathered in a bucket on the floor. It’s a cautionary tale about the consequences of living a criminal life. Equally, there’s the comic folklore (and sometimes true) stories of what are really inside some of the mass produced processed meats we consume–a narrative played out perfectly in the 1972 film Prime Cut, where a corrupt cattle rancher grinds his enemies into sausage meat.’

I gulp and think of the news this morning about about Tasty Chicken n’ Pizza, spectacularly shut down after trails of feces were found in the restaurant, mingled with mice droppings and chicken juices. (There was no soap to be seen on the entire premises.) ‘I’ve been eating Tasty all my life and it’s never done me any harm.’ Commented one friend sharing the story on Facebook. My stomach dances a jig as I return to the entrails/sausages, with their now very current resonance.

‘What primarily interested me here were the consumer mechanisms that urge us to believe that mass-produced goods are made in perfectly sterile environments, where robots and humans negotiate each other with an endless balletic precision. But the veil is dropped and the reality that some multi-national corporation has subcontracted out production to a dingy manufacturer in a developing country with outdated machinery and no workers’ rights.’

This dialectic–between our social conscience and our unmitigated desires–our compulsion to consume, persists throughout Flynn’s Half-Life of a Miracle exhibition, that surveys some of what the artist created over a decade (though the passing of ten years is almost imperceptible in the works.)

The language of advertising, entertainment, film and TV is seductive and sensuous, even when their goals are often malevolent. Flynn exploits the same technique, creating a visual hook that leads to much larger, wider narratives, truths and untruths. Our entire world is based on the construction of myths, from law to money to cheese (Pop historian Yuval Harari explains this phenomenon as necessary in order to bind together any community that consists of more than 200 people.) They exploit our contradictory nature: We want to believe in beauty and in a final, moral truth but the two rarely align, especially when viewed through a lens.

‘People are meant to be manipulated by the use of colour in my work, are meant to be left in a position where they are emotionally torn between the beauty and the emptiness. The computer is the perfect vehicle for driving this idea home.’

The supernatural quality of objects, seen through the eyes of a fetishistic consumer, leads Flynn to smoothly transition towards a contemplation of Hollywood films and advertising to religious iconography and talismanic leaders. They, too, satisfy our need to believe in something bigger.

‘ “Half-life of a miracle” is a quote from Sir James Goldsmith the billionaire tycoon. Goldsmith used this phrase when he was talking about quantifying his achievements in relation to the ecological biosphere and palace he had created for himself at Cuixmala, Mexico. This manufactured paradise was like a supersized version of William Randolph Hearst’s palace that Orson Welles recreated in Citizen Kane; but when Goldsmith’s biosphere went wrong–say, for instance, when there was a surge in the mosquito population –rather than balancing his biosphere through the introduction of more birds, bats and frogs he simply would spray DDT. Or say, for instance, if sharks swam into his bay, again, rather than accept that they were part of the equilibrium of his environment, he would have his security staff out on boats dropping dynamite on them.’

We’re a funny breed. Not unlike that strange cheese.

‘Pat Flynn: Half Life of a Miracle’ is showing at Manchester Art Gallery until 17 April.

Pat Flynn, cheeses, 2015