The New School of Paris Through Its Pioneering Women (1945-1964) at Perrotin in New York explores an unsung moment in Paris after World War II, focusing on some of the women artists, art dealers and art critics who helped shape it. The term “New School of Paris,” an extension of the so-called School of Paris that flourished between the 1900s and the 1940s, emerged as New York eclipsed Paris as the centre of the art world and abstraction trickled into the French market—albeit with some resistance.

The art historian Thomas Schlesser organised the exhibition in collaboration with the Archives de la Critique d’art, the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, Genève, and the Fondation Hartung-Bergman, where he serves as director. He argues that France never recovered from Robert Rauschenberg’s triumph in the 1964 Venice Biennale, after which “most of the networks in Paris were forgotten” and its former relevance dwindled.

Born in the aftermath, the New School of Paris was met with criticism and remains understudied in French scholarship. This is perhaps because it was “not a glorious moment for French art,” Schlesser explains, but also because its grouping of artists defied simple stylistic categorisation. It was a “moment” rather than a “movement,” he adds because the latter would denote “a common struggle and mission agreed between all the members, whereas this was more fluid—more about freedom of creation and exchange.”

The exhibition features a 52-minute documentary and significant works loaned from several private and public collections, narrowing down its scope to the women who shaped the moment and the diverse roster of artists who have been linked to their stories, including figures like Geneviève Asse, Georges Mathieu, Serge Poliakoff, Pierre Soulages and Zao Wou-Ki. Here are some of the must-know names from this moment in the art world:

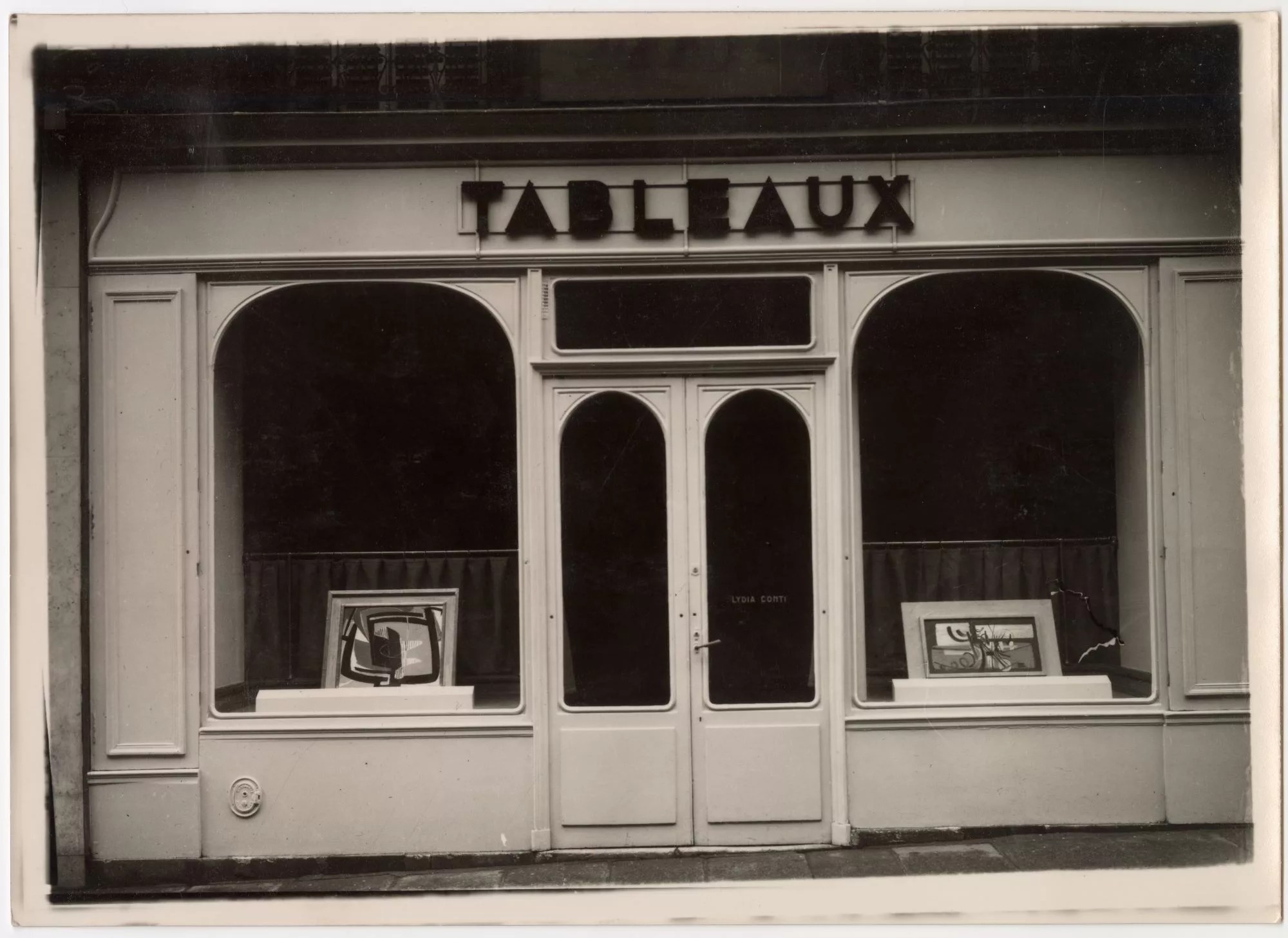

Lydia Conti, Gallerist (1902-1982)

Through extensive on-the-ground research into the New School of Paris, researchers have revealed that Lydia Conti (born Lydie Desclozeaux) was the art dealer who “discovered” Pierre Soulages, Gérard Schneider and Hans Hartung—although her career was extremely short. She opened her eponymous gallery on 1 rue d’Argenson in 1947, where the windows were smashed after she displayed works by Schneider and Hartung in the street-facing vitrine; according to legend, viewers believed she was mocking them. The space closed in 1949, after which Conti briefly worked at the Galerie Carré before retiring from the art world. Until this exhibition in New York, there were no published photographs of Conti, and much less was known about her background. “When you dive into this period, Conti’s name reappears over and over again,” Schlesser says. “She’s a mythical figure, but there are no known archives. I don’t think people who visited the gallery imagined that they should take a picture or write something about this place or that she believed she would become a historical figure.”

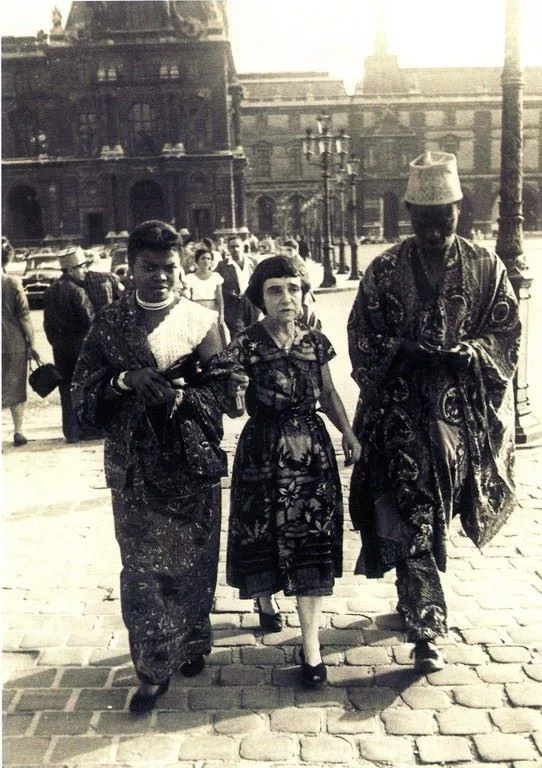

Madeleine Rousseau, Art Critic (1895-1980)

An art historian, curator, collector, art critic, painter and political activist, Madeleine Rousseau was an influential figure in the Parisian art scene who believed art had “entered a new existential phase after the Second World War,” according to Schlesser. She was a fervent supporter of abstraction, and she wrote several significant texts on the artists of the New School of Paris (including a 1949 catalogue for gallerist Lydia Conti for a group exhibition by Soulages, Schneider and Hartung). After World War II, she was the editor of Le Musée Vivant (The Living Museum)—the first “anti-colonial” French art review, where she focused on non-European artists. Rousseau believed in the democratisation of art and was expelled from the Communist Party in 1949 allegedly for her support of abstraction, which the party deemed “bourgeois, decorative or mystical,” Schlesser says. “But even painters who didn’t agree with her in terms of political views supported her views on art and freedom.” At the end of her life, Rousseau suffered from economic hardships. “The art critic Michel Ragon said he once saw her in a bourgeois district of Paris with her head in the trash.”

Betty Parsons, Collector and Art Dealer (1900-1982)

“It is true that the main defenders and promoters of the New School of Paris were women, but especially in the United States—they were all women,” Schlesser says. Alongside figures like Peggy Guggenheim, the American art dealer and collector Betty Parsons was one the few to support the artists associated with the New School of Paris, although her support was brief. Best known as an early champion of Abstract Expressionism and for her highly experimental programming, Parsons held an exhibition in New York in 1949 titled Painting in 1949: European and American Painters, featuring works by Soulages, Hartung and Schneider, following in the steps of Lydia Conti in Paris. But the show was admittedly “not a huge success,” Schlesser says, and Parsons famously reshifted her focus to younger generations of American artists. “As far as we know, she didn’t pursue the idea with much persistence after that,” the curator adds.

Myriam Prévot, Gallerist (1923-1977)

The art dealer Myriam Prévot co-founded the Galerie de France with her partner Gildo Caputo in the early 1950s, a space on rue Saint Honoré that sought to rival the bigger nearby galleries like Galerie Charpentier and the Élysée Palace. Like her peers, Prévot showed artists like Soulages, Wou-Ki, Hartung and Poliakoff, and also represented the artist Anna-Eva Bergman—a key figure of the New School of Paris—from 1958 onwards. With modest success in Paris, Prévot made the leap stateside in 1975, contributing to simultaneous exhibitions devoted to Hartung at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and in a gallery space. However, the exhibitions were deemed a failure; the Met leg of the show received a scathing review from the late The New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer, who asked: “Why? Why Hartung?” The backlash reportedly had a severe impact on Prévot. “She was in despair and committed suicide shortly after, some believed, because of the failure of the shows,” Schlesser says. “It was a sad end.”

Anna-Eva Bergman, Artist (1909-1987)

Once represented by Myriam Prévot, the Norwegian painter Anna-Eva Bergman approached her work with an “almost mystical ambition,” Schlesser writes in his book Luminous Lives: A Biography of Anna-Eva Bergman (2023). The artist studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Oslo and at the School of Applied Arts in Vienna before relocating to Paris in 1929, where she enrolled at the André Lhote Academy and met Hartung (whom she married twice in her lifetime). In her work, Bergman explores themes related to cosmology and the golden ratio. In an article published in March 1958, the German art critic Herta Wescher spoke of Bergman’s “infinite extensions.” Although she died in relative obscurity, there has been a recent renewed interest in Bergman’s paintings. In 2023, her work was included in the acclaimed exhibition Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.

Written by Gabriela Angeleti