In a moment of increased sensitivity to racial disparities within cultural programming, artists’ identities are often the object of focus as part of wider decolonisation projects. For Nalini Malani (b.1946) and Huma Bhabha (b.1962), such trends are far from straightforward, and not necessarily welcome. At the most basic level, the partition of British India in 1947 means that although both were born in Karachi, Malani was technically born in Pakistan; Bhabha in India.

Both are now showing work in the UK which, according to the galleries’ literature, share themes of post-colonial legacies, displacement, war and violence. But in many ways, they are worlds apart. At BALTIC, Gateshead, Bhabha’s Against Time displays her iconic, towering sculptures and works on paper; Malani’s Can You Hear Me? plunges audiences at London’s Whitechapel Gallery into an immersive cacophony of news fragments and violent fictions.

In 2006, economist Amartya Sen published Identity and Violence, a philosophical study whose roots lay in the author’s experience of Indian partition in 1947, but which was heavily influenced by recent conflicts in Kosovo, Rwanda, Israel and Palestine. “Many of the barbarities in the world are sustained through the illusion of a unique and choiceless identity” he wrote. For Sen, dividing the world too concretely along national, religious or sectarian lines had resulted in a poisonous global condition: hatred constructed by “invoking the magical power of some allegedly predominant identity that drowns other affiliations.”

Although its focus was geopolitical conflict, the book now reads as an early critique of the identity politics which has come to define the public sphere today. Sen recognised the potential fluffiness of his one world approach, but as the damaging labels of ‘Islam versus the West’ were solidifying in the wake of 9/11, he sought a global solution which appealed to shared interests rather than the religious fault lines which defined the period. The broader question that prompted Sen lives on today, in art as much as in politics and international relations. Are we to be defined by our membership of a particular group, or by the shared weight of our other numerous characteristics?

“I’m able to create an implied narrative, challenging viewers to create their own readings” —Huma Bhabha

In Bhabha’s exhibition Against Time, her sculptures are mounted on two broad white plinths at the gallery’s centre, creating set routes for audiences, while her paintings and works on paper face inwards, as if transfixed by their three-dimensional counterparts. Her monumental sculpture Receiver (2018) stands apart from the plinths on thick, charred stumps, its menacing body and crossed arms rendered in a luminous cyan. Bhabha uses Styrofoam, cork and bronze to construct torsos and explore the human form, allowing figurative boundaries to melt away as she combines African and classical influences with grotesque expressions and half-exposed armatures.

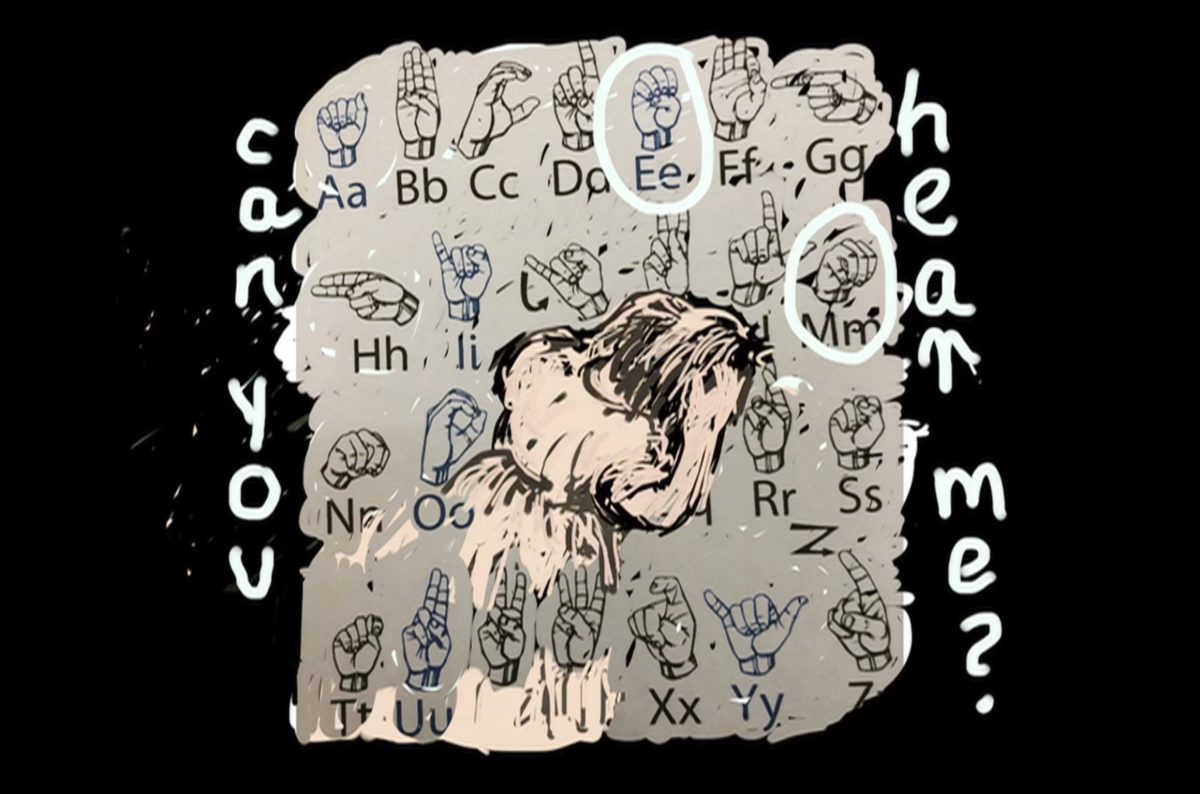

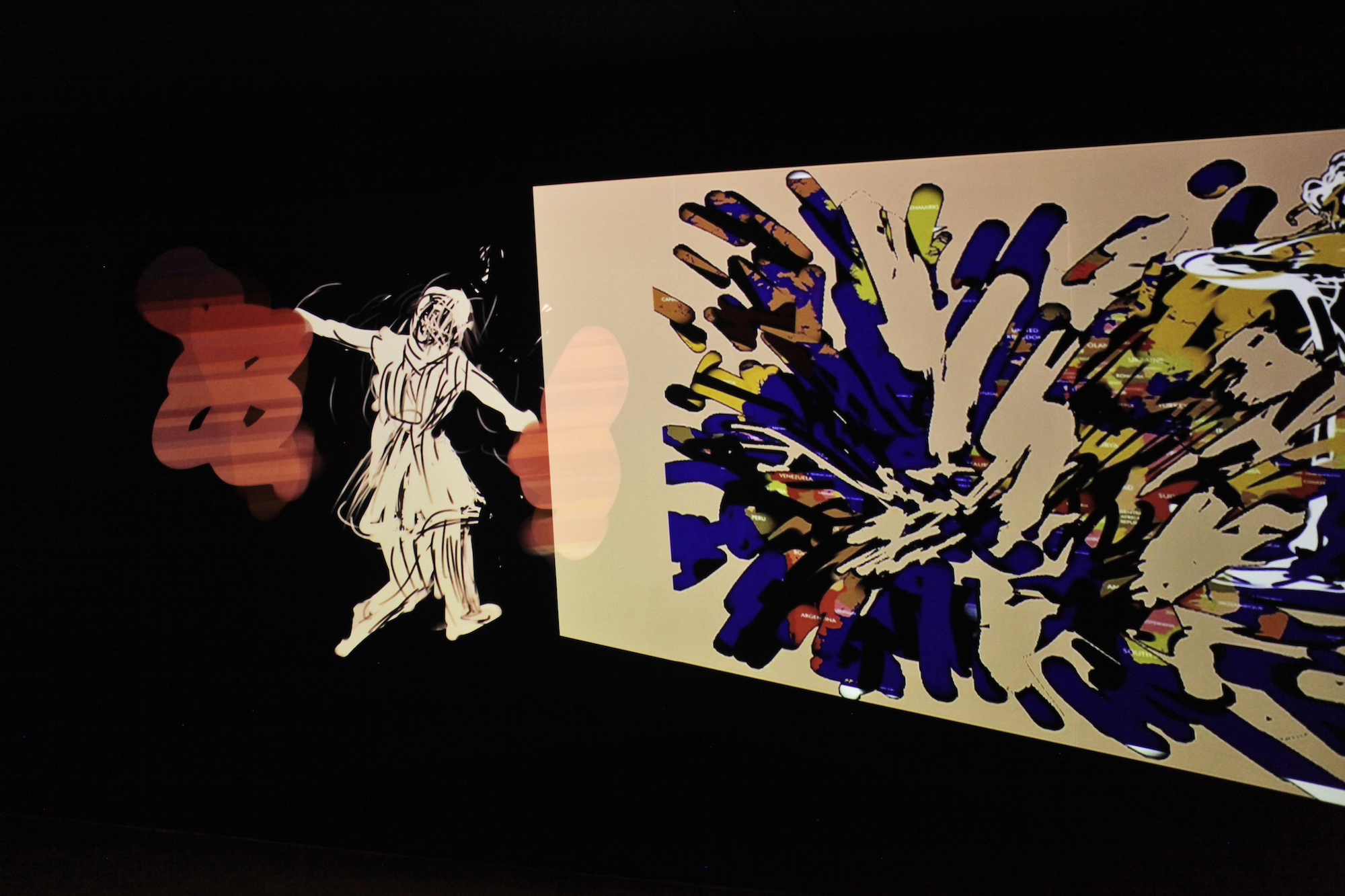

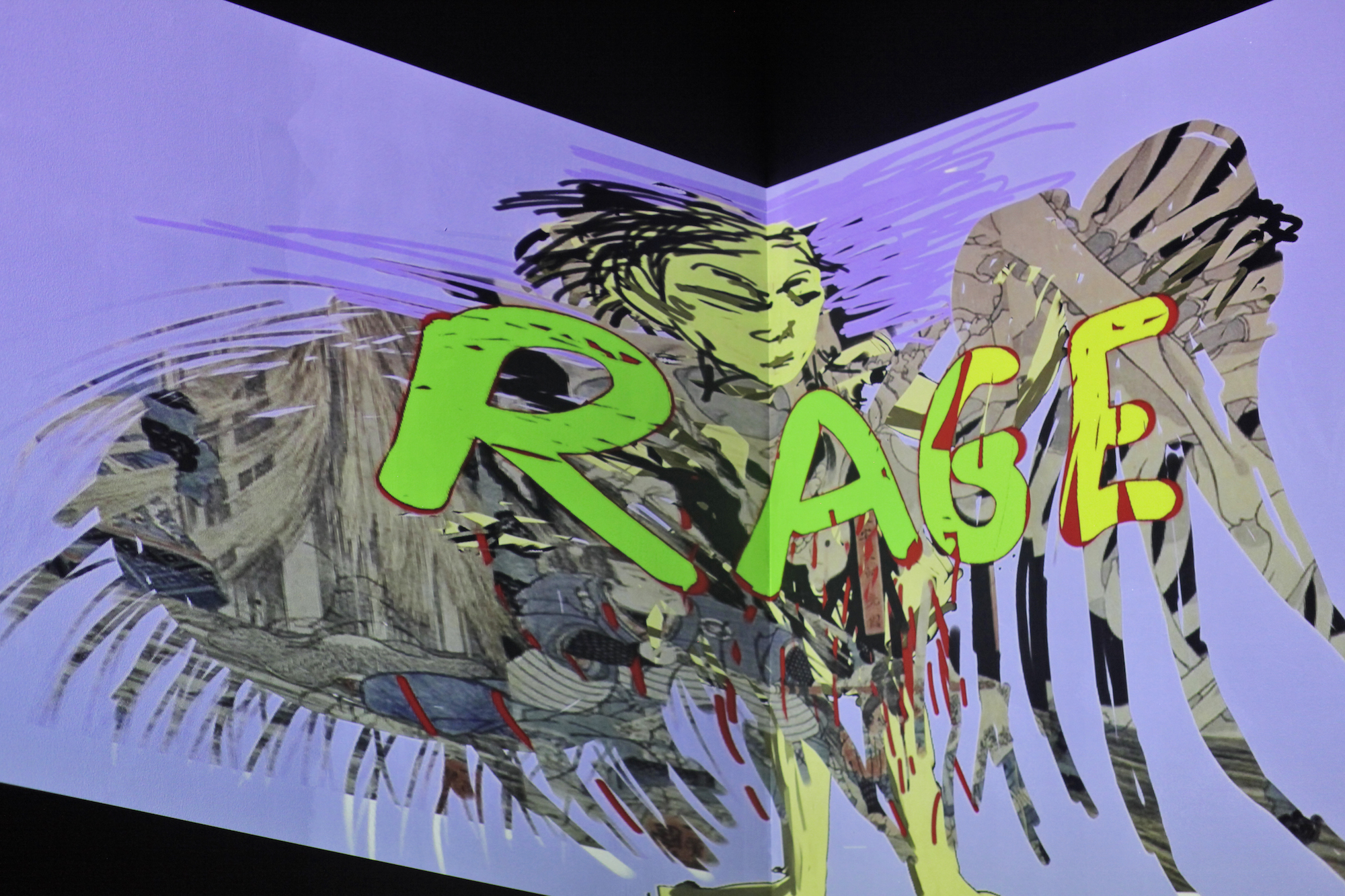

Malani’s Can You Hear Me?—a single work as opposed to Bhabha’s retrospective—is an immersive animation chamber: an explosion of flashing, frenetic sketches. The title refers to a 2018 Indian criminal case in which Asifa Bano, an eight-year-old girl from a nomadic Muslim community, was raped and murdered in Kashmir. Malani threads together world literature with these snippets of painful contemporary news, with several relating to India and Pakistan’s decades-long territorial conflict over Kashmir of which Sen is so scathing. In response, Malani uses textual collage to skewer the futility of conflict: “If there was an observer from Mars, they would probably be amazed we have survived this long,” reads one Noam Chomsky quote flashing across the walls.

For Bhabha, meaning starts with material rather than message. “Even though the sculpture is static, my mark-making and my expressions take response to the materials I am working with,” she says. We Come in Peace, her 2018 installation for the garden of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, featured Benaam, an enlarged figure in a semi-prayer pose, its face looking directly downwards and inflated hands stretching out ahead. The work materialised from Bhabha’s tactile approach: clay covered with a plastic sheet to keep it moist, leaving some audiences confused by the final sculpture. Originally conceived to commemorate war victims, the work became a disruptive yet dignified reminder of anonymous personhood.

“Even though I am of Pakistani origin, my interest has never been in making work about my identity” —Huma Bhabha

“I’m able to create an implied narrative,” Bhabha says, “challenging viewers to create their own readings.” These ambiguities—and a destruction of the self—are key to her practice: a shifting of agency from artist to artwork which places the work, rather than Bhabha herself, in conversation with the long history of classical sculpture. Using familiar materials allows viewers to situate the work within everyday experience rather than reaching for the artist’s prescriptions. Bhabha’s identity remains at a distance. In Atlas (2015), rubber tyres are sliced and laid flat on the exhibition’s pure white plinths, at once flaccid but also undulating and snake-like.

“Even though I am of Pakistani origin, my interest has never been in making work about my identity,” Bhabha says. “It is more about making pure art and responding to materials that allow me to be creative.” When Pakistani landscapes do feature, they are selected primarily for their rustic qualities. “I started photographing parts of Karachi near the city beach,” Bhabha explains. “It’s an area which reveals the landscape without any construction; I was fascinated by the idea of using unfinished construction sites or foundations as imaginary plinths for monumental sculpture, which is what I drew on them.” In Untitled (2011), an arid landscape is overlaid with a faded white skull, logo-like and barely human. Pakistan as an earthly stage for an alien life form.

And yet, Bhabha’s work does address issues of colonialism and contemporary politics through this focus on physicality. Unlike Malani, whose work deals directly with caste-related violence in India, “I’m not speaking about a specific incident and I’m not illustrating a specific time in history,” Bhabha says. Politics and identity are viewed as omnipresent, slow-moving entities, acting upon the work in subliminal, inevitable ways rather than being incorporated via the artist’s judgement. “The so-called War on Terror has taken up 20 years of my life,” Bhabha says drily. The omnipresence of geopolitics ties it to her art, rather than historical events acting as conscious themes. When Bhabha has spoken in the past about the desecration of sacred Islamic sites in Iraq and Yemen, it is through the lens of materiality, not identity.

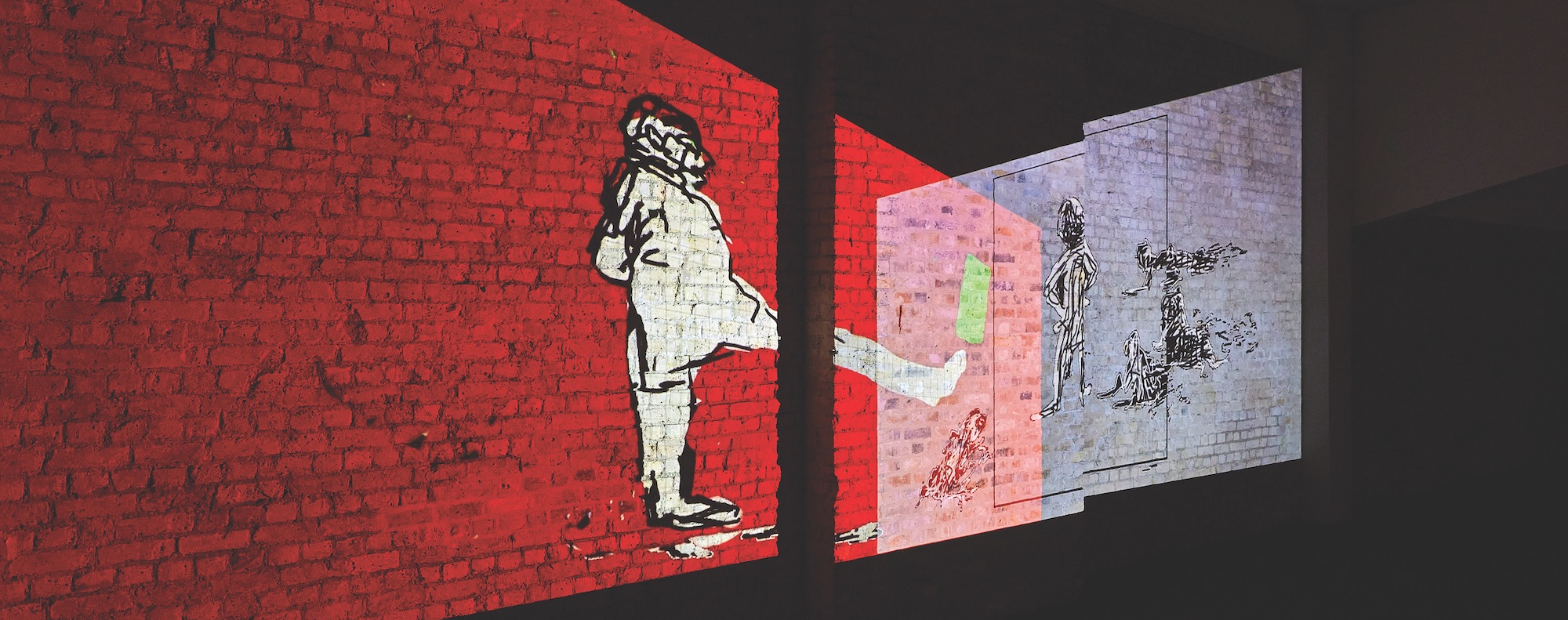

Whereas Bhabha allows meaning to emanate from these “implied narratives”, Malani’s Can You Hear Me? is something of a paradox in relation to Sen’s theories. Malani at once draws our attention to the extremes of religious and sectarian affiliations in India against which Sen warns, while also creating a work which is highly specific to her own politics of identity. “I see Can You Hear Me? as a peek into my brains,” she says. “I intentionally make my animations with this speed and loop them. It is the same pace of fleeting thought bubbles that I feel my mind works in.” In the chamber, sketchily drawn figures jump across the gallery walls, interspersed with flashes of red which illuminate the brickwork.

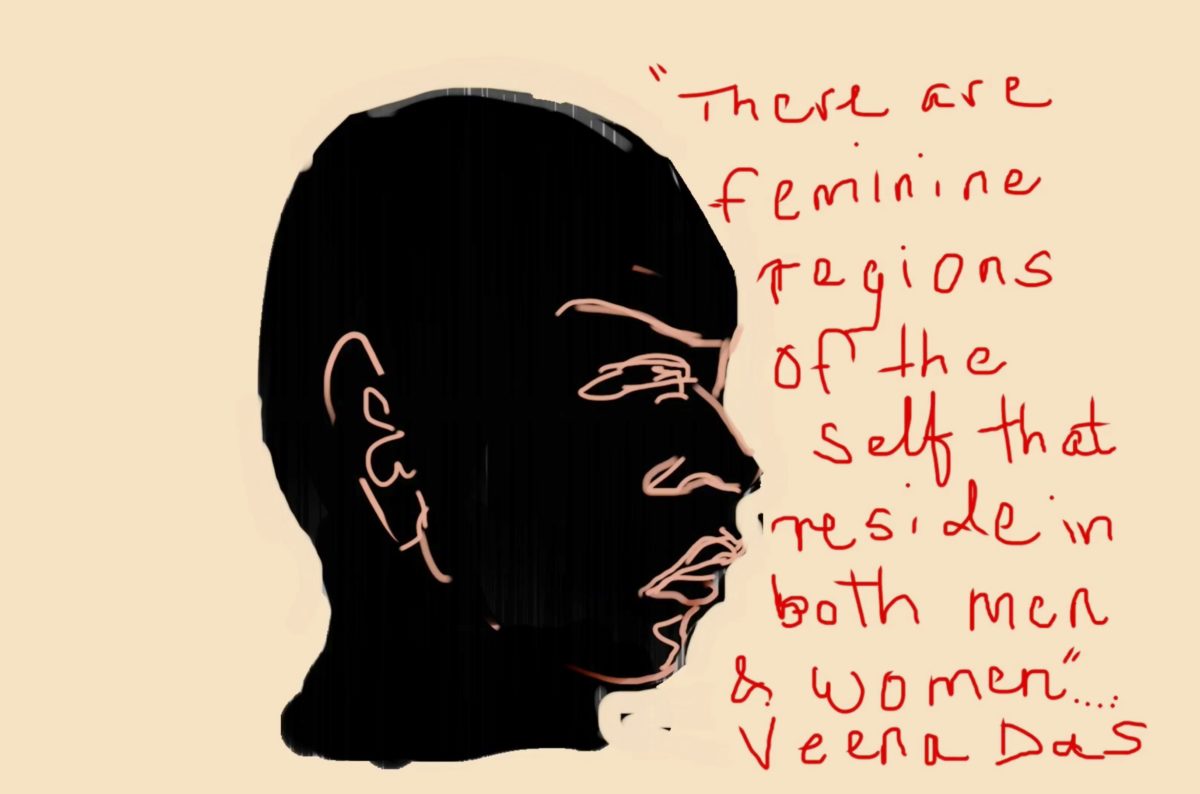

Quotes are drawn from Hannah Arendt, Veena Das, Milan Kundera and others—“all writers, historical or contemporary, who are engaged with the subaltern, the dispossessed,” says Malani. Accessible snippets like Samuel Beckett’s “Try again. Fail again. Fail better,” sit alongside more targeted lines aimed at authoritarian leaders: “Pity the nation whose sages are silenced and whose bigots haunt the air” (Lawrence Ferlinghetti). Malani uses this curatorial process to encourage diversity, “incorporating text in my art works like annotations, through which we see our own situation in a larger perspective,” she says. Can You Hear Me? begins with the artist, but it quickly becomes an open library.

- Left: Nalini Malani, Can You Hear Me? (still), 2018. Courtesy the artist

- Centre: Feminine Masculine, 2018. Courtesy the artist

- Right: Ubu Roi (still), 2018. Courtesy the artist

Malani’s practice has historically responded to specific incidents throughout partition’s long afterlife. Remembering Toba Tek Singh, her 1998 video play, connects the history of Karachi with India’s nuclear experiments of the same year, straddling the line between art and activism. “It was even proposed that it should travel along the border or India and Pakistan as a conscience-raising vehicle,” Malani says. But like Bhabha, whose work draws heavily on ancient mythology, Malani also turns to fiction as a tool, particularly when seeking to amplify voices who have been erased throughout history.

“I go further than re-contextualisation when I rewrite certain parts from a female perspective,” she says of her sources. Malani cites a long interest in the Greek figure of Medea, who she has continually repurposed as a colonial metaphor: “In Can You Hear Me? Medea appears rhythmically again and again in each of the projections, howling against the inequities and violence we face in our daily headlines.” She is not the only figure updated for our times. Lewis Carroll’s Alice is the protagonist of the exhibition. “She isn’t this doll-type figure in a fairytale landscape anymore,” Malani explains. “She is contemporary: we read about her being raped or suffering collateral damage when hit with pellet guns in Kashmir by the riot police.”

“I incorporate text in my art works like annotations, through which we see our own situation in a larger perspective” —Nalini Malani

This suggests the artist’s role as near-authorial, writing her historical fiction into our collective future. Bhabha has ultimate faith in her audiences to create their own fictions; her trust in the gaze in-part informed her decision (taken around 2000) to leave her sculptures incomplete, exposing the materials and drawing attention to the making process. “It’s almost as if you’re looking through the sculpture, into the sculpture and then it looks back at you,” she says.

The ways in which audiences experience the two exhibitions spatially is central to understanding how identity governs these artists. In Against Time, audiences can walk all around the sculptures, viewing them from multiple angles in order to land on a preferred perspective. In Can You Hear Me? the work encloses us; we are implanted into Malani’s world, with little room to manipulate it but endless material to engage with.

Bhabha absents herself from her work, allowing audiences to fill in the real and imagined gaps within her storytelling. Identity is a collaborative, involved process between artwork and viewer, not to be defined by the accidentals of the artist’s birthplace or age. For Malani, recognising the importance of identity—whether racial, gendered, religious or class—is not myopic, but a pathway to highlighting the injustices committed in its name. Both speak differently to our times, but taken together, they advance Sen’s cause for an intricate, plural politics of expression.