Cristina Lucas at Manifesta 12

Palermo is a town with a varied cuisine that runs from rough and ready street food to modern bistrot sophistication. But of all the recipes associated with the city, one holds a particularly eminent status. This is the pani ca’ meusa, a Rabelaisian sandwich composed of a hamburger bun stuffed to bursting with a thick slop of lard, cheese, veal lung and spleen. It smells like death and looks like something drawn from David Cronenberg‘s sickest imaginings, but as with so much in this city, its origins and—yeuuch—contents are a living reflection of local history. It may well be apocryphal, but apparently the sandwich is a product of different recipes dreamed up by Palermo’s medieval Arab and Jewish communities, the dairy element coming from the former; the offal courtesy of the latter, who controlled the butchery trade.

Such cross-cultural borrowing is everywhere here, and small wonder. In some form or other, Palermo has existed as a city for nearly three thousand years. Founded by the Phoenicians in the early first century BC, it has since passed through the hands of pretty much every major Mediterranean power: the Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Saracens, Normans, Hohenstaufens, Habsburgs and Italians have all exercised power over what is now the Sicilian capital. More so even than other cities of the region, the streets of central Palermo present a forceful testimony to the tastes of its myriad conquerors. Baroque churches abut classical ruins. Arabic crenellations top out the bizarre, nominally Gothic cathedral. Elegant nineteenth-century boulevards spill out into chaotic piazze that play host to the kind of street life you’d never believe existed outside of neo-realist cinema.

- Left: Michael Wang. Right: Cooking Sections. Both at Manifesta 12

This summer, Palermo has been infiltrated by a crowd rather less fearsome than the invaders of the past: the curators, journalists and assorted hangers-on of the contemporary art world. The reason for their presence here is Manifesta 12, the latest iteration of the peripatetic international art exhibition that has pitched up in a different European city every other year since 1996. While it doesn’t have the cultural prestige of some other biennales, Manifesta has earned itself a reputation for both earnestness and eccentricity. On the one hand, the exhibition’s Amsterdam-based organizers make a point of foregrounding social and political issues relevant to the host city; on the other, recent editions have provided a venue for some emphatically zany art projects.

- Left: Trevor Paglan. Right: Zheng Bo. Both at Manifesta 12

Manifesta 12 is all this, but more so. Stretching across more than a dozen venues dotted from the city’s old centre to its industrial suburbs, it is characterized by a sombre mood of geopolitical high mindedness and rote anti-Americanism, skirting over everything from the Mediterranean refugee crisis to US foreign policy to disaster capitalism and Sicily’s still troubled relationship with the Mafia. Yet whenever it gets too didactic, you stumble across a work like Zheng Bo’s Pteridophilia—a daft and rather sweet video in which a group of seven young men walk into a Taiwanese forest and engage in what a caption describes as “intimate contact with ferns”.

“While it doesn’t have the cultural prestige of some other biennales, Manifesta has earned itself a reputation for both earnestness and eccentricity”

- Left: Lungiswa Gqunta. Right: James Bridle. Both at Manifesta 12

The art itself is a mixed bag, much of which may already be over-familiar to anyone who’s kept a close eye on contemporary art developments over the past five years or so. International art biennale stalwarts (Tania Bruguera, Kader Attia and James Bridle, to name a few) share space with post-internet doom merchants (Trevor Paglen, the reliably po-faced Laura Poitras) and a new vanguard of interdisciplinarians (Berlin’s Peng! Collective, Turner Prize nominees Forensic Architecture). So, if you travelled to the Venice Biennale or/and Documenta last year, it’s unlikely you’ll learn much. Yet while there is little here that feels truly vital, Manifesta 12 is nevertheless essential viewing.

Put simply, it provides a framework to navigating Palermo, an astonishing but formidably complicated city. The organizers have convinced city officials to let them exhibit in a dazzling range of venues, many of which are normally off-limits to the public. A tour of all the city centre venues will take you from a bombed-out church to decaying palazzi to totemic Fascist era colossi. Along the way, you’ll get lost repeatedly but in the process come closer to discovering what makes this extraordinary place tick.

Fallen Fruit at Manifesta 12

As a place to start, Piazza Magione—the de facto headquarters of the Manifesta circus—is as good as any. It’s a vast space, carpet bombed during the war and neglected for decades until revived by grass-roots community projects. In its centre is the looming hulk of an abandoned convent, around which children play football and enterprising sorts sell beer and soft drinks from portable coolers. Heading out towards the port, the next venue is the city’s Botanical Garden. Kew Gardens this isn’t: covering around thirty acres, it is a decrepit maze of bulbous cacti, tropical ferns and brobdingnagian palm trees. In a building close to the entrance, Palestinian artist Khalil Rabah has hoarded a mass of junk from Palermo’s markets into small exhibition spaces visible only from the structure’s upper floors, creating a ramshackle mini-museum of objects that range from the banal to the politically loaded. What it has to do with the garden itself is unclear, but it makes for Manifesta’s single most uncanny moment.

“A tour of all the city centre venues will take you from a bombed-out church to decaying palazzi to totemic Fascist era colossi”

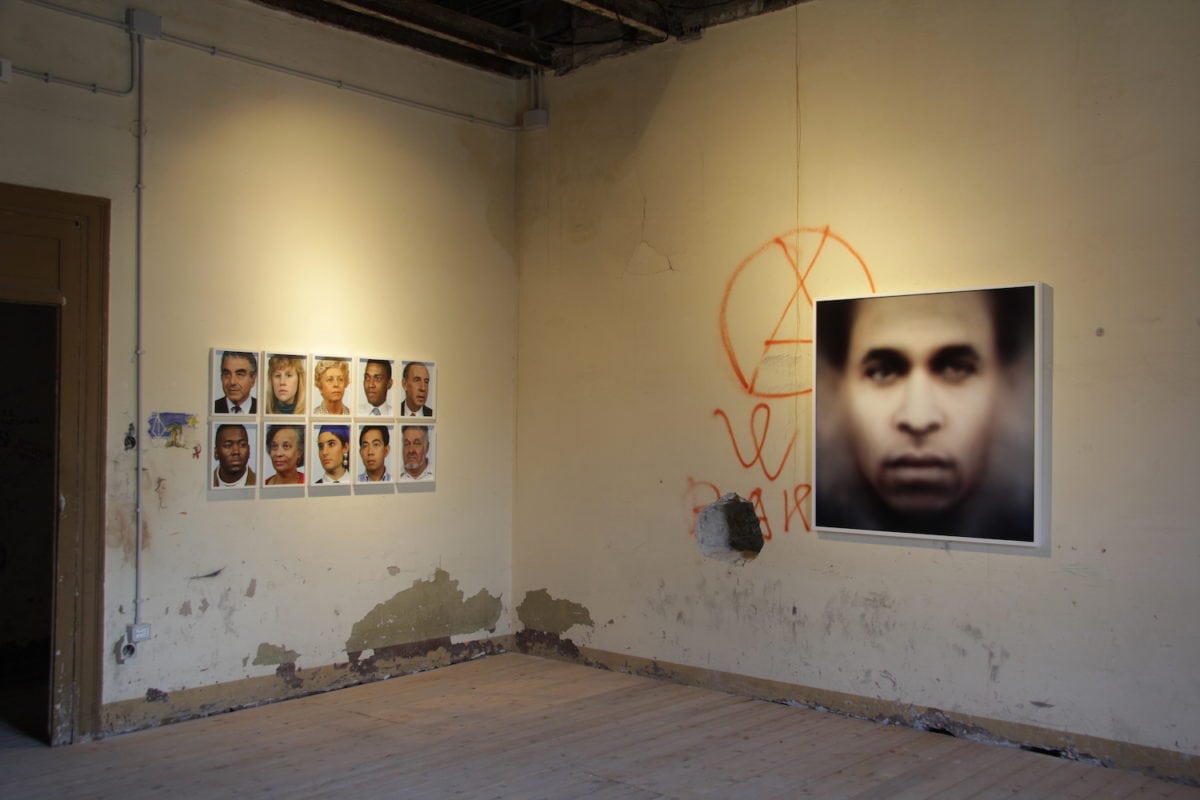

Back inland, the highlights trail leads to the Palazzo Ajutamicristo, a once elegant space whose walls now form a canvas for decades of graffiti. Tania Bruguera has filled a large room with political cartoons, banners and videos documenting local people’s ultimately unsuccessful struggle to stop the American military installing a satellite monitoring station in one of Sicily’s last cork forests. A few rooms on, Lydia Ourahmane recreates a 2014 installation composed of twenty oil barrels containing mobile phones that emit a ghostly scream of feedback. It’s fascinating—not so much for its physical characteristics, but for the exhaustive documentation Ourahmane provides into its genesis and its exploration of economic stasis in her native Algeria.

From there on, suffer Nora Turato’s formidably irritating sound installation in the Oratorio San Lorenzo—the beautiful church from which a Caravaggio Nativity scene was stolen in 1969—and head to the eighteenth century Palazzo Costantino. Once one of the city’s grandest structures, it fell into disrepair and has been sealed off for the best part of a century. This is the first time its doors have been opened to the public since the 1960s, and its scuffed but still awe inspiring courtyard dwarfs the art installations set up within.

“Kew Gardens this isn’t: covering around thirty acres, it is a decrepit maze of bulbous cacti, tropical ferns and brobdingnagian palm trees”

The only work which really operates in harmony—if that’s the right word—with its setting is Spanish artist Cristina Lucas‘s Unending Lightning, a six hour video about the history of aerial bombardment screening inside a palace built to commemorate the wounded of Mussolini’s colonial wars. Against the backdrop of a world map, the screens chronologically flash up information about every single airstrike conducted on civilian areas between 1911 and the present day. The dates fall onto the map like Google pins, creating blacked-out areas over central Europe, Vietnam and most recently, Syria. It is a harrowing experience, all the more powerful for showing nothing but the raw data of atrocity.

At 8pm, the venues close for the night and the city’s sleepy daytime character is transformed into something resembling a pagan ritual. Small squares occupied earlier only by long shadows become riotous as crowds of young Palermitans spill in and out of bars serving lethal €3 negronis and plastic tumblers of coarse Nero d’Avola. Smoke from the ubiquitous open-air grills battles terrible Euro-dance pop for control of the air. If this all sounds like a bit much, head north to Via Ettore Ximenes in the Borgo Vecchio, where the (quite bracingly) unpretentious Grigliate di Carne e Pesce da Michele serves twitchingly fresh octopus and smoky veal panini for a couple of euros. Then again—if you’re possessed of a stronger stomach—you could always try the pani ca’ meusa…

Photos by Wolfgang Träger