Writer Desmond Vincent speaks to artist Uthman Wahaab about identity, religion and his most recent work Khalwa Room II.

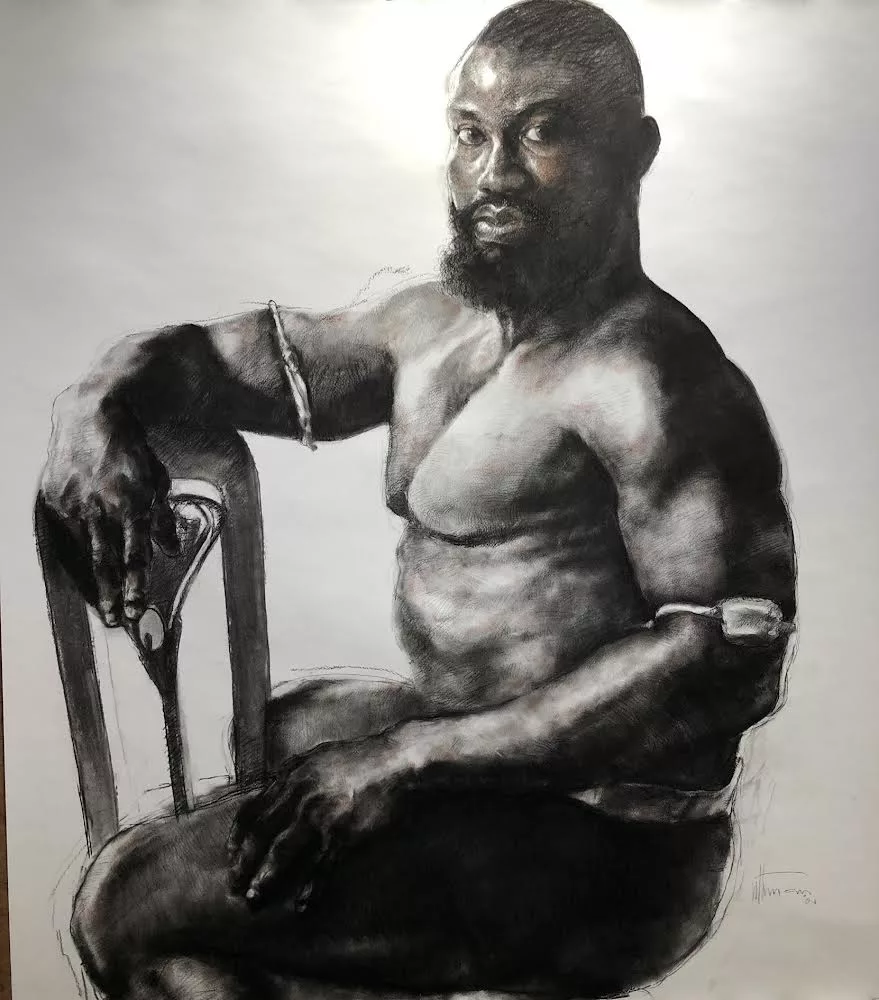

When making art, Uthman Wahaab runs towards the complexity of human reality. It is a trait that has marked his practice and has turned him into one of the more exciting artists coming out of Lagos. At the most recent iteration of Art X Lagos, West Africa’s premiere art fair, the artist was one of the highlights of the fair where he was the sole exhibitor for Lagos-based gallery, O’DA Art Gallery’s debut. Where other galleries had several artists exhibited—as is the norm—O’DA and Uthman put their eggs in one basket for the showing. It paid off, as Wahaab’s exploration of body image and beauty standards was an instant hit. The featured series Where Is Chichi?, Wahaab shares with me, was inspired by a woman he met years back who helped enlighten him on the world of shifting beauty standards. When Wahaab met ‘Chichi’, body standards in the country were changing, leaving plus-size women—who at one point in Nigerian, and African culture at large, were considered the standard of beauty—in the dust. His approach to storytelling is non-judgemental even while holding a mirror to a pervasive social phenomenon, seemingly a signature of his work. It is this desire, to hold a mirror to his native society, that inspires work like Victorian Lagos— thematically miles apart from Where is Chichi? —and aims to tackle the effects of colonialism on Lagos and Nigerian culture-wide. After observing how Lagos citizens were influenced by Victorian fashion, he takes given products and merges them with instantly recognizable Nigerian stylistic choices. Taking it further with Hybrid Theory, he serves as a muse and model while raising several questions concerning identity in an attempt to encourage the acceptance of African identity as well as Western ideals of growth.

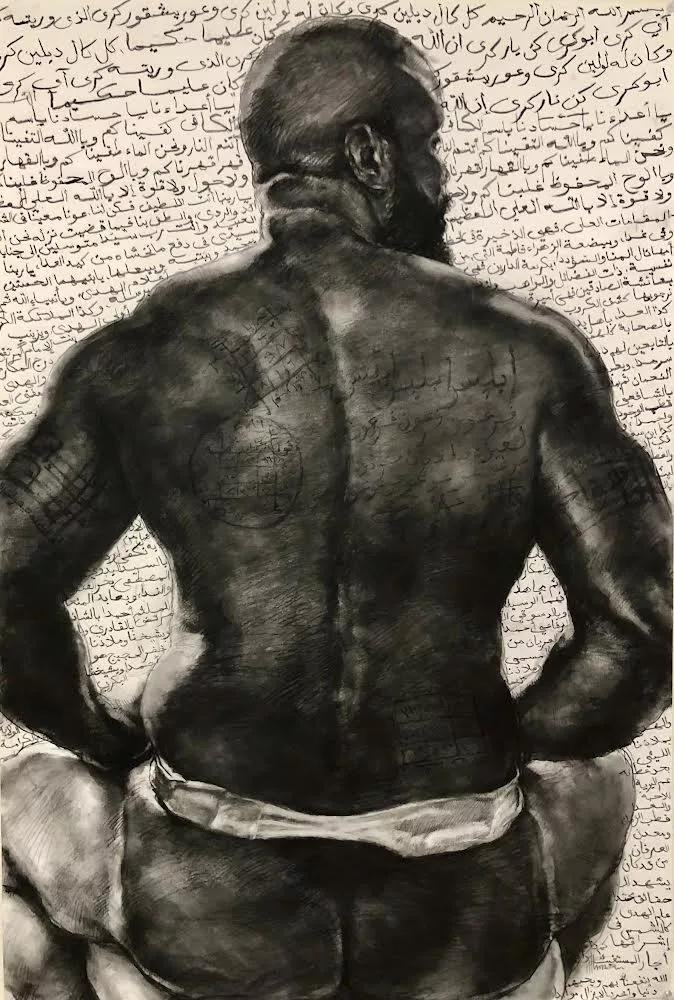

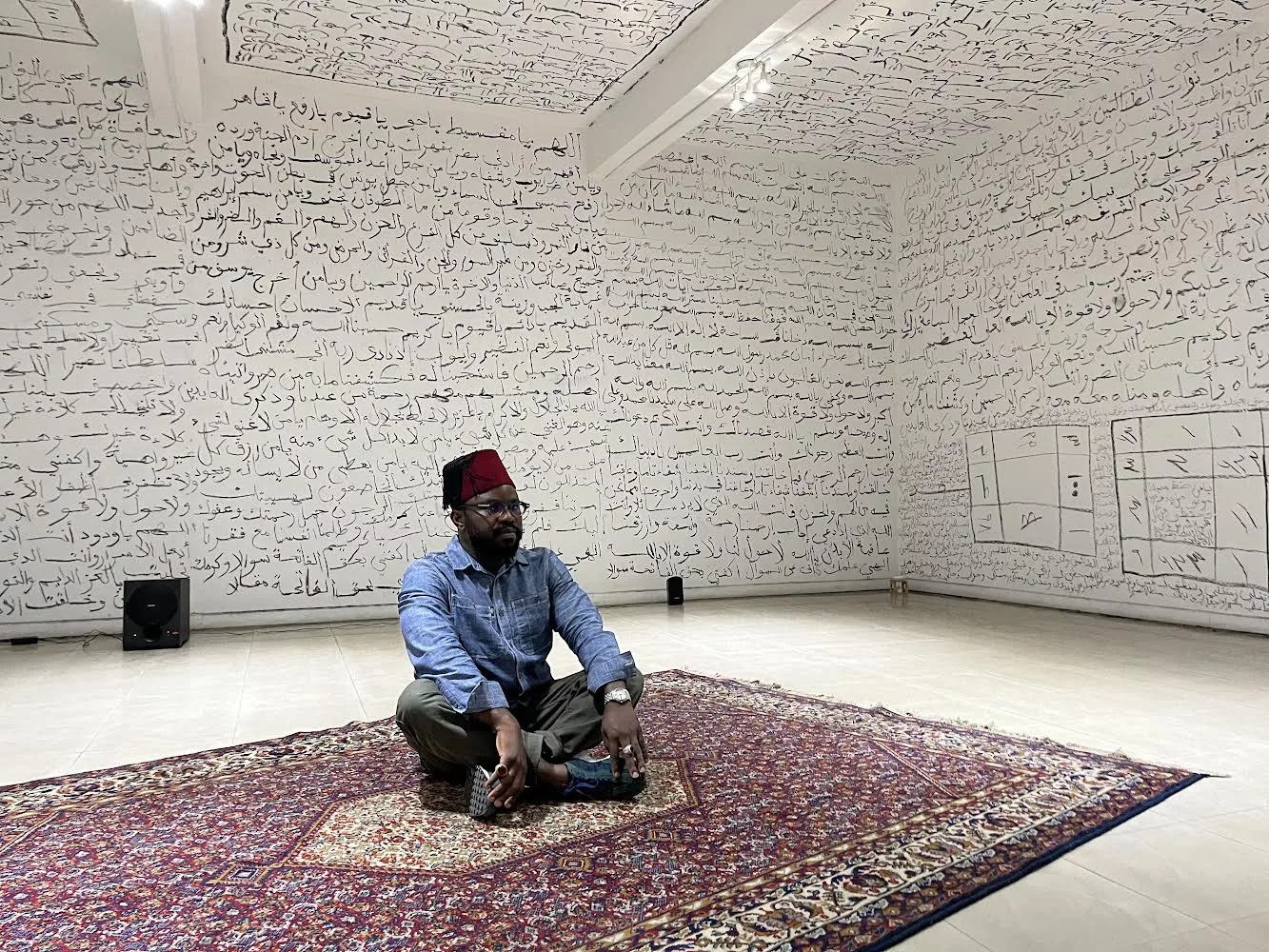

In Wahaab’s more recent work, titled Khalwa Room 11 in reference the practice in Sufism that prioritizes spiritual isolation to worship God, he tackles spirituality, mysticism and the role space plays in the religion. As a gesture towards this role of space, he performs one of the cornerstones of Sufism, an Islamic religious practice he tells me he was introduced to as a kid. Right off Khalwa Room II, Wahaab launches back into his busy schedule which takes him off to London, where I manage to catch him on a call for a conversation on his practice, making contradictory art and more.

DV: Your most recent exhibition Khalwa Room II is a great place to start, can you tell me about the inspiration behind it?

UW: My inspiration started from wanting to have a more contemporary way or form to engage in this practice. I realise this kind of spiritual practice is disappearing and this is an attempt to recreate this form of engagement and spiritual practice that the current generation can tap into. The elders are very much known to be engaged in this practice and do this and it’s something that should continue. In Islam, Khalwa is a spiritual seclusion and I’ve seen my dad do this several times when I was growing up. They went to isolate themselves for just a day to reflect and so when I saw him I realised people don’t do that anymore which is interesting especially because the world is becoming more and more complicated.

DV: What was the process of translating that into a concrete artistic experience like for you?

UW: I looked at it as an artist. First of all, I see a performance in that process, and then I see defined sacred moments one could have with oneself and I realized that is art—because art is very sacred to artists, it is something that is for you first. So I try to juxtapose that with this ideology together and see how I can create something that will reflect both the spiritual practices and the artistic practice. That led me to do more in my research on this process of deconstructing. Deconstruction in the sense that it’s still not going to water down the essence of this practice. I decided to create a more contemporary approach to that and reform and reinvent the process. In seclusion, sometimes you have some prayer that you have to recite and sit in the process, which is very intense. So it becomes a space where you just immerse yourself and meditate and reflect.

DV: You’ve said that the black identity crisis typically inspires your work but what exactly is the black identity crisis?

UW: For me, it’s more about the confusion that has been created over time. We tend to want to carry a particular identity and that identity at the end of the day becomes contradictory with the idea of your identity. For instance, we were both talking but I don’t know where you’re from as we’re speaking in English but I know that maybe you are Nigerian. Even though for me, our real identity is our language.

As an artist now as much as I want to be identified as Nigerian, from Nigeria, there’s still this aspect of the situation that doesn’t want me to stay there. And that became a crisis for me because it’s something that I struggled with. I was in Lagos for four months for work but then something is not just aligning, because [Nigeria] is disrupting my work process. Sometimes I enjoy the chaos because the chaos is something to do but there is always the tiptoeing about where you want to be and what you want to become.

DV: That makes sense. In your Victorian Lagos series, the Nigerians featured are imagined to be directly feeling the impact of colonialism but is there any significant difference between a Nigerian from that time, that era and a Nigerian of today?

UW: Nothing has changed. It’s even more complicated in a more sophisticated way. In those days, from my research, people who were freed from slavery came back looking like that with European attire because there is always a need to show, a need for you to prove that you are better than the people you met in Nigeria. So you come back with the European attire and the struggle of this identity because you carry the tribal marks. After all, these marks are an identity for a tribe. So you carry that and you still want to imbibe the European culture because that has become an identity for you.

Those dresses are a symbol of freedom so they still need to wear them to show that they are free, even though they do not like it. I’ve watched several slavery and period films and even before you can show your certificate that you are a free slave, you need to dress a particular way, different from the linen the slaves would wear. It becomes an identity.

DV: Let’s take it a bit further. Your solo exhibition at ArtX featured a plus-size woman in various points of a mundane life but what I found so interesting was that you included the fattening room. Why was that important to you and was it essential to the story you were telling?

UW: I started this series in 2009, 2010. It started as a response to an encounter that I had with a lady with that body type who was suffering from anxiety about how people were treating her because of her body type. That reminds me of and was a response to the idea of beauty and how it keeps changing due to societal response to what they are confronted with. It still boils down to all these Western standards or ideals you know. When I was in high school, it was Orbobo, being plus-sized, that was the beauty standard. Orobo was a term for being sexy with that plus-size body type, and that standard became so popular that people were taking dairy pills to gain weight because if you do not have that body type you are not considered beautiful.

DV: When was this?

UW: This was the mid to late 90s then it continued to the 2000s, the Y2K. Then people became exposed to magazines and international beauty standards and that introduced us to ‘lepa’ skinny women as the standard of beauty. Then it became: if you are not ‘lepa’, you are not beautiful, and that affects a lot of women with large bodies because they become a sort of laughing stock which is what happened to the lady I met. For me, the idea of beauty is very subjective. Beauty is what it is to you based on how you can relate to those things. Then I realized that being fat as a standard of beauty has been institutionalized in Africa especially in Nigeria with the fattening room at some point. [A fattening room] is where you will be accommodated in a room for some time, and you’ll be taken care of to grow more flesh because when you grow more flesh you’ll get more beautiful. They still use that culture today.

DV: What goes into making something like the fattening room to ensure all of this, the culture, the context, is communicated?

UW: It is very important to me to bring out the African perspective where this was institutionalized especially to contribute it to the global discourse. Since 2010, I’ve been working on this. The social scale complicates this idea of beauty and self-acceptance so my work reflects those elements. In my early stage, I had the ladies isolate themselves in a room with a magazine, looking at these people and thinking they want to become like that and then it goes on holding a selfie stick where they have to create a version of themselves. Do you know the selfie stick allows you to show just one part of your face, and maybe your shoulder? So they create a new version of themselves. It is replaying itself now. History keeps repeating itself, You see it with the popularization of the BBL. Anyway, this subject became a muse for me to create this body of work which became my signature. After a decade of creating this work, I decided to create a fictional account of what this subject will have become. I met her only once, we lost contact. So this was me creating a fictional account of her life, that’s why it is called Where is Chichi? Is she somewhere lodging on a Malibu beach, has she found love? etc.

DV: I like to end a lot of interviews asking this, so I’ll ask you, who inspires you as an artist?

UW: I would say myself first because everything has to resonate with what I am thinking and I am feeling at that moment. That informs what to look at, who to look at, the situation to look into and the narrative to talk about. As a multidisciplinary artist, I am conscious about exploring and the major influence on that is Tata—I remember seeing his show in White Cube in London in 2015 where he displayed different layers of artistic interpretation or representation. They were painting sound, and there was a performance. It was huge for me.

Words by Desmond Vincent