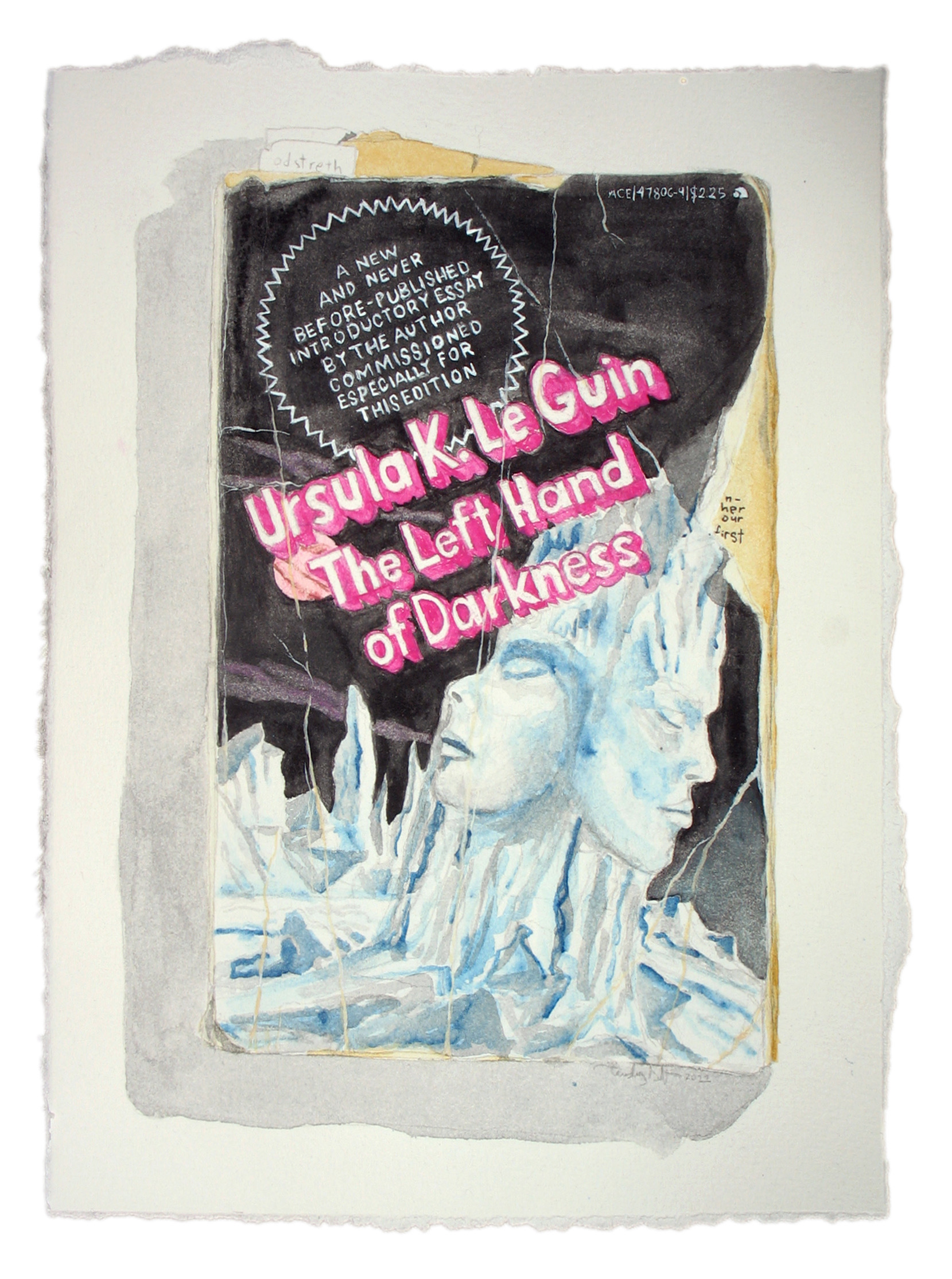

Tuesday Smillie, The Left Hand Of Darkness, 2010-2015. Courtesy the artist

As the country enters a complete lockdown and Dean Koontz’s The Eyes of Darkness continues to top the Amazon charts while an exasperated Stephen King tweets his followers to say no, it’s nothing like The Stand, science fiction has never seemed as necessary an art form through which to understand the ambient malaise we’re all living through. Yet, arguably, both readers and the art world had already turned to science fiction—or speculative fiction for those for whom “science” and “fiction” feel oxymoronic—for guidance well before this crisis.

We seek out dystopian narratives (Contagion, The Plague, Netflix’s Pandemic, to name but a few) with the same ghoulishness with which we monitor the Guardian’s Coronavirus Live Blog; it is one way to make sense of an incomprehensible situation. But before we were seeing scenes of army trucks transporting coffins out of Italian towns or photos of an uncannily deserted Trafalgar Square, the art community was already re-engaging with possible futures and speculative fiction in a spirit of (perhaps surprising) hopefulness.

Motivated more by questions of identity, gender, historical violence, generational hopelessness and mental health than the current lockdown, artists have been using speculative fiction in recent years to invoke radical utopias and other worlds as imaginary alternatives to an unsatisfactory political present.

“We seek out dystopian narratives with the same ghoulishness with which we monitor the Guardian’s Coronavirus Live Blog”

Loosely concerned with the creation of fantastical worlds, speculative fiction has been used as a beacon by artists and curators in the unpredictable times that preceded this deeper uncertainty. Marxist sci-fi scholar Darko Suvin defined speculative fiction as an exercise in “cognitive estrangement” where ceasing disbelief and the mental jump into the unreal made it “a genre showing how ‘things could be different'” and therefore quintessentially political. Its popularity is not specific to the art community either—even before the coronavirus rumblings, sales in sci-fi and fantasy books had doubled since 2010.

Already accustomed to speculative and creative thinking, the art world seems better prepared than most for this moment of societal unmooring. The level of precarity and hopelessness shared among many artists (particularly in the UK since December’s general election) could be behind this return to the political potential of speculative thinking. Certainly, numerous artists have made it integral to their practice.

In her 2019 Turner Prize winning project DC Semiramis and her ongoing Dark Continent series, artist Tai Shani takes inspiration from the medieval literature of Christine De Pizan’s The Book of The City of Ladies, which tells of an allegorical city inhabited and made of women. Shani adapts it in a style close to 1970s feminist sci-fi to create elaborate and complex worlds whose interior logics and purple prose question the patriarchy and its structures, and offer a platform to female self-individuation.

Irregular and popular publications such as Victoria Sin

’s Dream Babes zines, use the “what if” of speculative fiction to imagine alternative structures and identities “as a productive strategy of queer resistance.” Sci-fi here is used as a way of looking at gender and sexuality, free from the weight and inherited preconceptions of history.

South-east London artist-run gallery Jupiter Woods hosted several exhibitions and one-off discursive events in the last year influenced by speculative fiction, such as the recent Very Very Far Away’s “Future Rangers” reading series. This looked at space and how it shapes the “collective imagination in order to propose more ‘democratic’ alternatives and… a proposed utopia.” The gallery’s director Carolina Ongaro confirms that the genre is often referenced in the present climate, and “signals the need for the making of new imaginary spaces that can keep us grounded together at a time when it’s easy to feel unable to cope with events.”

Eoin Dara, co-curator with Kim McAleese of Dundee Contemporary Art’s Seized By The Left Hand programme, inspired by Ursula K Le Guin’s cult classic The Left Hand of Darkness, says her writing was “a lodestar” in thinking about how to “use our imagination productively in order to hold space for other voices with care and compassion.” To Dara, the current moment presents the perfect opportunity to engage in the mental exercise that speculative fiction demands, proposing “radical imagining” as something that is “not a luxury but a vital part of being human.”

“We need new imaginary spaces that can keep us grounded together at a time when it’s easy to feel unable to cope with events”

Writer and performer CAConrad’s writing (which appeared in the DCA show along with that of writer Huw Lemmey) borrows from speculative fiction and mixes fable, ritual, and a repurposing of language, particularly in their (Soma)tic Poetry. “People who have unobstructed access to their imaginations are already used to building new structures,” they say, adding that a confidence in the transformative power of imagination is needed now more than ever “to understand that there is a never-ending channel to the conversations that can change the way we think we know the world.”

While a lot of the work varies when speculative thinking meets the art world, there is undeniably a shared interest in radical utopian action that has politics at its heart. Katie Stone, the cofounder of Utopian Acts, a research body that investigates the relationship between activism and utopianism, was slated to take part in The Whitechapel Gallery’s now (somewhat ironically) cancelled launch of “Science Fiction”, part of its Documents of Contemporary Art book series.

Stone suggests that the current return to speculative thought is understandable in that it “offers a wide variety of tools for both communities and individuals in crisis—when our normal routines are disrupted we have to find new ways of being.” She believes it’s an exciting time for science fiction art and utopianism. “Speculative fiction is a tool for radical, utopian action,” she says, adding that people who explore and work in the genre offer a valuable service, “imagining new worlds in order to make our world more liveable.”

The gift of good speculative fiction is the plausibility of the worlds it creates. In a climate of uncertainty, we have to remember the plausibility of the different worlds that artists and writers put forward. Speculative thinking continues with growing courage. It has the power not only to foretell potential doom, but to propose radical, utopian and real political alternatives. In the coming weeks especially, it can provide us with blueprints for the future, and an escape to a transcendent unreality far away from the sickening present.

Stay the Fuck Home

Our special series offers creative approaches to the long days of self-isolation during this global crisis.

EXPLORE THE SERIES