This feature originally appeared in Issue 31.

Justin Vivian Bond has a platinum-blonde fringe, an East Village flat in some disarray and a sweet old cat, who sleeps, silent as taxidermy, for the duration of my visit. The flat will soon be traded for a house in upstate New York—hence the mess, the artist explains, and as for the cat: “She’s been my most ardent and tender lover for many, many years.” V’s rich voice dips to deliver bon mots, followed by trills of laughter. (Bond, who is transgender, prefers the honorific Mx and the pronouns v, they or them.) Even off stage, v’s delivery is flawless.

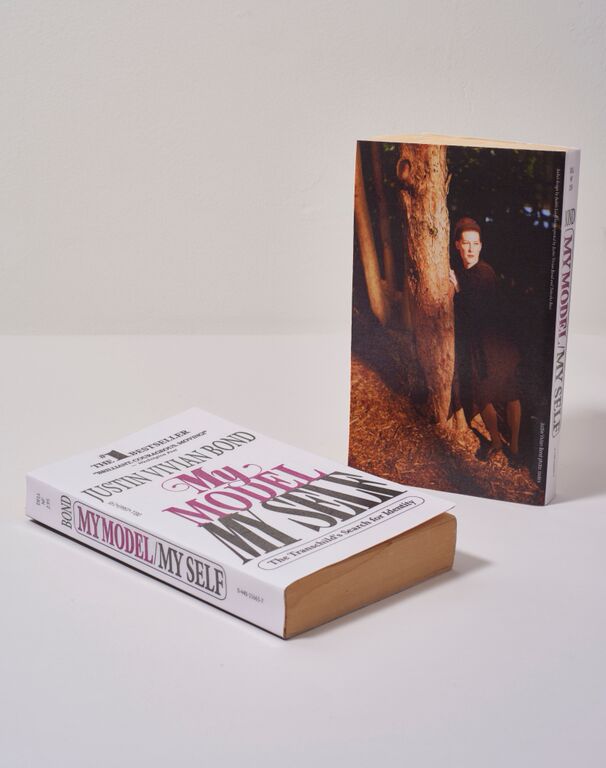

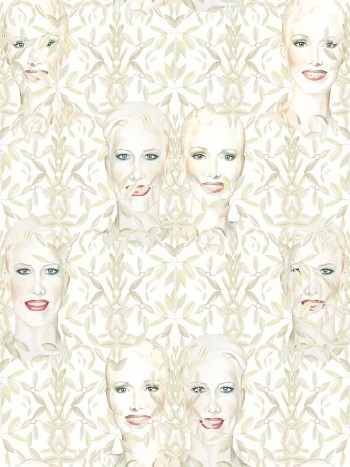

A self-described trans-genre artist, Bond is a prolific artist, activist and curator. V is the author of the heart-grabbing coming-of-age memoir Tango: My Childhood, Backwards and in High Heels, has acted in numerous films and has had solo exhibitions of painting, installation and performance in New York and London. But v is perhaps best known for performing as the louche, foul-mouthed singer Kiki DuRane, half of the cabaret duo Kiki and Herb. Although the act emerged from the rough-and-ready San Francisco drag scene of the early Nineties, by the mid-2000s they were playing Carnegie Hall and nominated for a Tony Award. Now fifty-three, Bond performs as Mx Justin Vivian Bond, a hard-won identity long in the making. An upcoming musical tour will follow the credo “glamour is resistance!”

In the meantime, Bond has been hard at work curating New York Live Arts’ Mx’d Messages, a festival of art and ideas held this spring. Its offerings were widely interdisciplinary, including panels on Afrofuturist art, trans theology and the influence of the Queercore punk scene, as well as workshops, performances and film screenings. At the heart of each Mx’d Messages event was a central question: What would it be like to live in a world without binaries?

Why was it important that Mx’d Messages include artists and creatives from so many different disciplines?

People assumed that because I’m transgender the festival would be about trans issues, but to me that includes everything. If you’re capable of seeing that gender is not binary then you can see other things in non-binary ways as well. Religion, for example. The differences between religions are very minor, but the struggles and fights over those minor differences are extraordinary. If we can find ways of approaching these subjects without being so radically extremist, that would certainly be to everyone’s benefit. So I wanted to have a panel on trans theology. How do we know that God is gendered? What gender is the Holy Spirit? That sort of thing. There’s a rabbi named Mark Sameth on the panel who wrote an article in the New York Times called “Is God Transgender?” about how early biblical texts used non-specific and non-binary gender language and that people’s genders would change.

In a past interview you referred to God with the pronoun v, the same one you prefer for yourself.

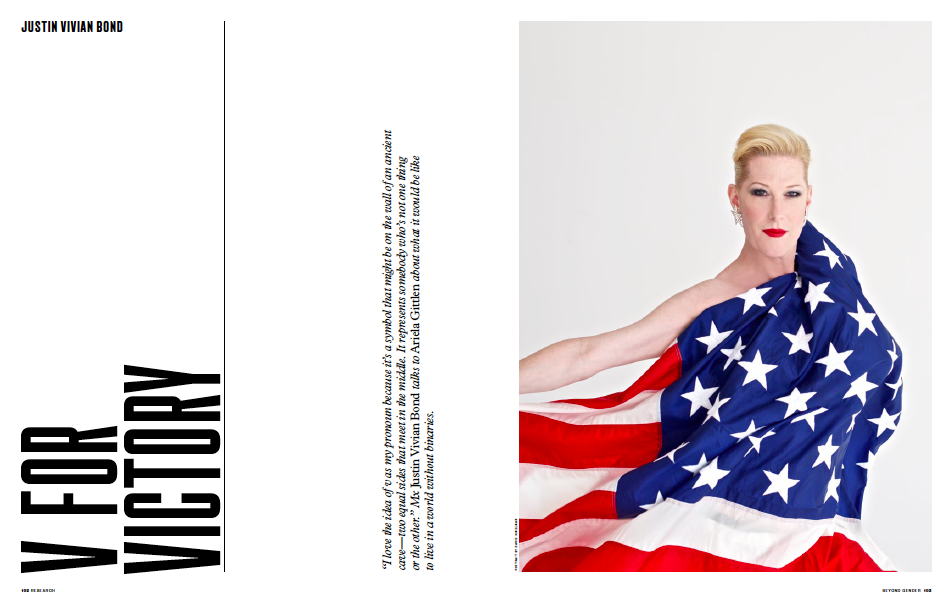

Did I? Although I’m comfortable with they and them now, I love the idea of v as my pronoun because it’s a symbol that might be on the wall of an ancient cave—two equal sides that meet in the middle. It represents somebody who’s not one thing or the other.

Is a world without binaries a practical possibility or just a utopian ideal?

I don’t know if it’s a utopian ideal, but I do think it’s an interesting point of departure, especially considering how polarized the world is right now. One panel is organized by Siri May who works with OutRight Action International, advocating for the LGBT population at the United Nations. They don’t really use the term LGBT, they use “sexual orientation and gender identity” because people throughout the world don’t think of themselves as LGBT—they have different ways of categorizing themselves. So if you take away binaries and you take away these categories, how do you advocate for people? I don’t say that a world without binaries is the ideal world, but there are new ways of looking at things that hopefully we’ll discover.

In your memoir Tango you wrote that when you learned about the burgeoning Women’s Lib movement as a child, you made a sign and marched around the neighbourhood in a bid for kids’ liberation. Why did you see the struggle for women’s rights as connected to your own?

As a kid, I felt that if feminism was successful, the roles that men and women could play would completely open up. It would allow people who felt trapped in the roles they were assigned to be liberated from them. That was my mistaken childish perception which I have somehow retained through all these years and that I’m still working for.

Was there a moment when you realized how powerful having the right words could be?

I remember being a kid and I would be doing something and my father would say, “Boys don’t do that.” Having just done it, I thought: Well, either boys do that or I’m not a boy. I realized that the most logical explanation was that my father was wrong. Many people are aware of the limitations of language around gender, but because we don’t have the words to express it we’re stuck in patterns of behaviour that limit us and our interactions. I’ve tried to popularize certain words that created new ways of dealing with concepts that there wasn’t previously language for, such as non-binary or gender-fluid, using the word Mx, and throwing v out there as a gender pronoun. I want a medical and social record of who I am so I’m not effectively put back in the closet in twenty or thirty years when I’m not longer able to articulate who, or what, I am. The fact is that if you’re trans and not insisting you’re trans and on the use of the proper pronouns, your family and friends are more comfortable completely ignoring your truth. The most exhausting part of being trans is that you constantly have to insist on something that’s a given for so many people.

Does the generation that followed you have a different relationship with the language of gender?

In many ways they’ve surpassed me. When Kate Bornstein and I were touring with her play Hidden: A Gender, in which I played an intersex character who had secondary sex characteristics of both genders, we didn’t have words like “non-binary”. That was in 1990–91, when all of a sudden queer studies and gender studies started to be taught in colleges so there were all these students who had access to all of this information. I would have coffee with them after the show and they would teach me all these things. They were putting language to the things I already knew because I was living them. So it’s not just a one-way street; it goes in many different directions again, part of the non-binary nature of it. The generation that came after me is in many ways much better educated around these issues.

You work in many different media including writing, performance and painting. Do you jump back and forth daily between different disciplines?

I do sort of jump back and forth because I manage my own career. I don’t like to plan too much. That’s why this year all my shows are called Justin Vivian Bond Shows Up because I want to be able to respond to whatever’s happening in the world at the time. I sing and I talk, that’s what I do. Hopefully the combination of words and songs adds up to something more than just words and songs.

So there’s an element of surprise?

It keeps my musicians interested and it makes me feel free. It also keeps me engaged in the process, as opposed to just playing something and not thinking about it. I don’t like to see people who are just saying the same thing over and over again, even if they say it well.

Last year you began teaching a course on installation art at Bard College. Did anything surprise you about teaching?

That the students are very intelligent, but they don’t actually know anything. The richness and depth of this world is something you can’t know by the time you’re twenty-one. I was lucky—one of the benefits of being socially ostracized and having a bipolar best girlfriend was that we mostly just stayed indoors, read a lot and listened to music. So I knew a lot more than most people about the McCarthy era, feminism and ridiculous romance novels from the book of the month club. She was into science fiction and I was into biographies, so between the two of us we went through a lot of books.

I was forced to read a lot too as a kid because my parents refused to buy a television.

In seventh grade my grades were bad so I was grounded from the TV for a marking period. That’s when I started drawing, painting and reading. It was the smartest thing my parents ever did. If they hadn’t, none of this would be here and I’d be a complete fucking idiot. I worry because most people skim the surface of so many things, but they don’t have the opportunity and the time to get to know about anything deeply.

What about the internet? It can be as distracting as TV, but it also allows people to build communities and access information in new ways.

I think the internet is really important. My mother is an intelligent woman, but when I was young, her ability to deal with the issues that I was facing was nonexistent because she had no context for me. She still doesn’t really, but she’s a little bit more open. If I had insisted that she learn about these things because I knew where to tell her to look, it might have made it easier on both of us. What I do now as an artist is contextualize things. I’m a contextualizer. That’s what Mx’d Messages is about, contextualizing all these ideas.

What’s your next big project?

I’ve been commissioned to do a new piece that will be shown at SFMOMA in March of next year, so Bard is giving me development space and resources to create a performance. I’m not calling myself the director or the writer, I’m the facilitator of this idea and I’ll have lots of people help me put it together. I’m giving everyone little roles. My friend Michael is really good at connecting people, so he’s the door. Nath Ann is my memory bank because he’s an ex-lover and really good at memorizing facts. I keep him on stage so I can go: “What am I thinking about?” He knows everything.

You must have a talent for staying friends with your exes.

I’d be so lonely otherwise! Generally, once I love someone, I love them. But like I say: The truth changes.