When you arrive in Dundee, you’re irresistibly drawn to the water. The city, with its handsome Georgian buildings, slopes down towards the Firth of Tay, with its rail and road bridges sweeping across the river. If you’re flying in, you land alongside its banks. The waterside feels like a natural setting for an ambitious modern landmark: the newly-opened V&A Dundee, designed by Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, as part of a billion-pound redevelopment of the area.

Dundee’s V&A feels immediately distinct from its related venues; London has the two original museums, housed in regal Victorian buildings (a V&A East is also proposed to open in Stratford in 2023), while the V&A collaborated on a design centre in Shenzhen, China, which opened last year.

“Its rugged, contorted, cliff-like concrete exterior juts out onto the Tay”

There’s no mistaking the presence of Kuma’s structure; its rugged, contorted, cliff-like concrete exterior juts out onto the Tay, forming a stark contrast from its next-door neighbour: the RRS Discovery ship used to sail early twentieth-century Antarctic expeditions by Robert Falcon Scott and Ernest Shackleton. It is a bold statement piece with a reported cost of £80.1 million; as such, it invites strong reactions. Some have been rapturous, others less swayed; the Dundonian taxi driver who dropped me near Kuma’s behemoth, quipped: “It’s just another place fer the seagulls tae shite.”

Naysayers should warm more to V&A’s interior; the atrium’s light oak timbers and limestone floors have been envisioned by Kuma as “a living room for the city”, offering a free, accessible public area for any visitors. There is a sense of lofty height and airiness rather than floor space (once you’ve factored in the ticket desk, café and gift shop), though there are tantalizing glimpses of the water through the steeply angled walls. The outdoor panorama fully opens up when you reach the first-floor balcony or the museum restaurant, which serves fancy remixes of Scottish cuisine (“haggis gnocchi, £13.50”).

- Dennis the Menace artwork by David Law. Published in The Beano, 30 April 1960

- Beckett videogame designed by The Secret Experiment

The galleries are located on the upper level: a permanent space devoted to Scottish design from 1500 to the present, and one for temporary exhibitions. Within the permanent gallery, the richness and range of Scotland’s innovations is immediately apparent; the collection is judiciously curated from the V&A’s vast archives and loans, spanning high fashion to trade textiles (Dundee was apparently once known as “juteopolis”, referring to its dominant jute industry), glassware, interior design, structural engineering and architecture (including Basil Spence’s brutalist dreams), theatre sets and much more. It feels genuinely outward-looking and impressively uncluttered.

This gallery’s central highlight is surely the Oak Room, painstakingly reconstructed from Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s 1907 design for a Glasgow tea room, in an era of radical social change including feminist enterprise and the Temperance movement. There is a reverential atmosphere within this sleek space, with its intricately layered wooden panels, low lighting, and nods to Mackintosh’s fascination with Japanese art (in contemporary turn, Kuma has cited Mackintosh as an inspiration). While the main museum structure feels consciously “new”, within this space we are steeped in history, even through the rich aroma of the Oak Room’s material.

Lemmings, designed by DMA Design, published by Psygnosis

What is also evident is the strength of Scotland’s pop culture. As you enter the permanent gallery, there’s an overhead screen playing footage from the 1991 hit platform videogame Lemmings, developed by the Dundee-founded DMA studio (which was later behind the first two instalments of the massive Grand Theft Auto series). Gaming is celebrated here, both as mass entertainment and experimental art. There’s also a small but punchy display of comic design, including much-loved creations from Dundee’s seminal DC Thomson publishers (notably The Beano), through to the multi-cultural takes on manga novels by Asia Alfasi, who moved from Libya to Scotland as a schoolgirl.

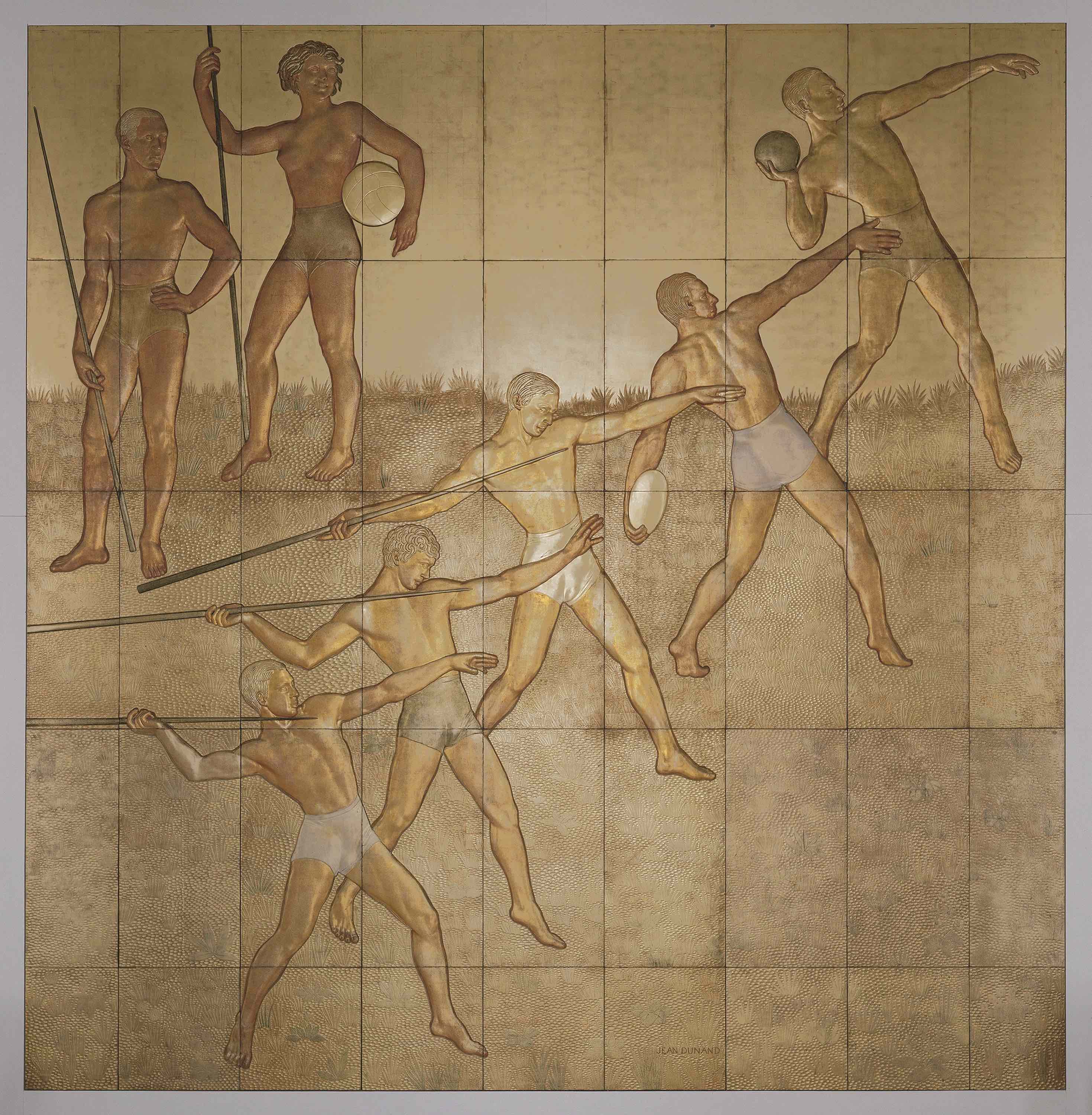

V&A Dundee’s temporary gallery puts its extensive space to effective use with the lavish Ocean Liners: Speed & Style exhibition, which ran at London’s V&A earlier this year. While this show hasn’t been radically adapted for its new home, it does reflect the significance of Scottish shipyards, where many of these “floating palaces” were originally constructed. The scale of this space really hits you when you view the opulent Olympian athletes, rendered in lacquered gold leaf for a gigantic frieze panel from Jean Dunand’s Smoking Room, onboard the 1930s French luxury liner the SS Normandie

. Art Deco treasures are actually all that remain of the Normandie; they were removed from the ship when it became destined for military service, and it was sunk in 1942.

Ocean Liners does bring out some intriguing juxtapositions. The entrance room makes note of the emigrant experience before succumbing to the first-class glamorama. Elsewhere, there’s a very queasy contrast between Arthur Heinrich Wilhelm Fitger’s epic 1901 oil painting Our Future Lies Upon The Water (taken from the Smoking Room on the Kronprinz Wilhelm), and the depiction of real-life tragedy in Fred Spear’s 1915 poster, prompted by the sinking of the Lusitania passenger ship by a German U-boat torpedo. Spear’s devastating illustration portrays a drowned mother cradling her infant, with the direct emotive entreat to the public in WW1: “Enlist”.

“The V&A Dundee invariably raises the question of whether art venues really can have a transformative power”

Ultimately, Ocean Liners evokes a nostalgia for luxury, aspiration and social ranking that is immaculate but not necessarily easy to relate to. Even in an exhibition of this size, it is possible to experience cabin fever.

The V&A Dundee invariably raises the question of whether art venues really can have a transformative power. Its arrival has prompted comparisons to Bilbao’s Frank Gehry-designed Guggenheim Bilbao, which made the Basque port city a world-class cultural destination. London’s Tate Modern has vividly reshaped the previously desolate Bankside district.

In Dundee, the big-scale regeneration had undeniably included some ugly developments, including the dreary new-build office and hotel blocks springing up around the waterfront. Yet there is also an exciting openness—both in its landscape (a large new public park is being developed near the V&A) and its spirit. The V&A Dundee does not feel purely like a branded “super-gallery” designed to dwarf its neighbouring institutions, but rather a further point of connection within a city that already has close-knit artistic communities. It forges a particular bond with the University of Dundee, and with the nearby DCA: a former car park converted into a multi-disciplinary arts space includes an impressive print studio. It feels like a symbol of solid possibilities, within a scintillating state of flux.

V&A Dundee is now open

VISIT WEBSITE