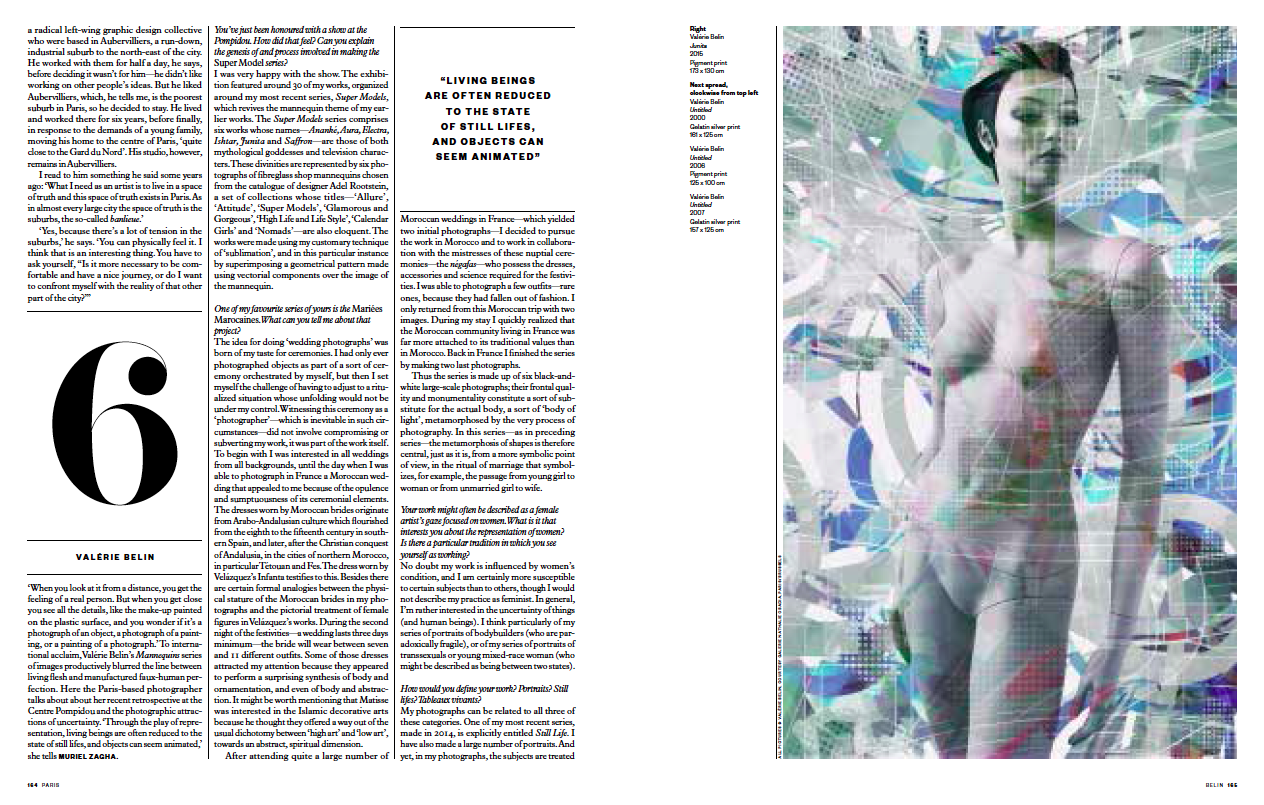

‘When you look at it from a distance, you get the feeling of a real person. But when you get close you see all the details, like the make-up painted on the plastic surface, and you wonder if it’s a photograph of an object, a photograph of a painting, or a painting of a photograph.’ To international acclaim, Valérie Belin’s Mannequins series of images productively blurred the line between living flesh and manufactured faux-human perfection. Here the Paris-based photographer talks about about her recent retrospective at the Centre Pompidou and the photographic attractions of uncertainty. ‘Through the play of representation, living beings are often reduced to the state of still lifes, and objects can seem animated,’ she tells MURIEL ZAGHA.

Note: this feature originally appeared in Issue 24 of Elephant.

You’ve just been honoured with a show at the Pompidou. How did that feel? Can you explain the genesis of and process involved in making the Super Model series?

I was very happy with the show. The exhibition featured around 30 of my works, organized around my most recent series, Super Models, which revives the mannequin theme of my earlier works. The Super Models series comprises six works whose names—Ananké, Aura, Electra, Ishtar, Junita and Saffron—are those of both mythological goddesses and television characters. These divinities are represented by six photographs of fibreglass shop mannequins chosen from the catalogue of designer Adel Rootstein, a set of collections whose titles—‘Allure’, ‘Attitude’, ‘Super Models’, ‘Glamorous and Gorgeous’, ‘High Life and Life Style’, ‘Calendar Girls’ and ‘Nomads’—are also eloquent. The works were made using my customary technique of ‘sublimation’, and in this particular instance by superimposing a geometrical pattern made using vectorial components over the image of the mannequin.

One of my favourite series of yours is the Mariées Marocaines. What can you tell me about that project?

The idea for doing ‘wedding photographs’ was born of my taste for ceremonies. I had only ever photographed objects as part of a sort of ceremony orchestrated by myself, but then I set myself the challenge of having to adjust to a ritualized situation whose unfolding would not be under my control. Witnessing this ceremony as a ‘photographer’—which is inevitable in such circumstances— did not involve compromising or subverting my work, it was part of the work itself. To begin with I was interested in all weddings from all backgrounds, until the day when I was able to photograph in France a Moroccan wedding that appealed to me because of the opulence and sumptuousness of its ceremonial elements. The dresses worn by Moroccan brides originate from Arabo-Andalusian culture which flourished from the eighth to the fifteenth century in southern Spain, and later, after the Christian conquest of Andalusia, in the cities of northern Morocco, in particular Tétouan and Fes. The dress worn by Velázquez’s Infanta testifies to this. Besides there are certain formal analogies between the physical stature of the Moroccan brides in my photographs and the pictorial treatment of female figures in Velázquez’s works. During the second night of the festivities—a wedding lasts three days minimum—the bride will wear between seven and 11 different outfits. Some of those dresses attracted my attention because they appeared to perform a surprising synthesis of body and ornamentation, and even of body and abstraction. It might be worth mentioning that Matisse was interested in the Islamic decorative arts because he thought they offered a way out of the usual dichotomy between ‘high art’ and ‘low art’, towards an abstract, spiritual dimension. After attending quite a large number of Moroccan weddings in France—which yielded two initial photographs—I decided to pursue the work in Morocco and to work in collaboration with the mistresses of these nuptial ceremonies—the négafas—who possess the dresses, accessories and science required for the festivities. I was able to photograph a few outfits—rare ones, because they had fallen out of fashion. I only returned from this Moroccan trip with two images. During my stay I quickly realized that the Moroccan community living in France was far more attached to its traditional values than in Morocco. Back in France I finished the series by making two last photographs. Thus the series is made up of six black-andwhite large-scale photographs; their frontal quality and monumentality constitute a sort of substitute for the actual body, a sort of ‘body of light’, metamorphosed by the very process of photography. In this series—as in preceding series—the metamorphosis of shapes is therefore central, just as it is, from a more symbolic point of view, in the ritual of marriage that symbolizes, for example, the passage from young girl to woman or from unmarried girl to wife.

Your work might often be described as a female artist’s gaze focused on women. What is it that interests you about the representation of women? Is there a particular tradition in which you see yourself as working?

No doubt my work is influenced by women’s condition, and I am certainly more susceptible to certain subjects than to others, though I would not describe my practice as feminist. In general, I’m rather interested in the uncertainty of things (and human beings). I think particularly of my series of portraits of bodybuilders (who are paradoxically fragile), or of my series of portraits of transsexuals or young mixed-race woman (who might be described as being between two states).

How would you define your work? Portraits? Still lifes? Tableaux vivants?

My photographs can be related to all three of these categories. One of my most recent series, made in 2014, is explicitly entitled Still Life. I have also made a large number of portraits. And yet, in my photographs, the subjects are treated equivalently: through the play of representation, living beings are often reduced to the state of still lifes, and objects can seem animated. The concept of the tableau vivant is closely linked to the history of photography; but paradoxically photography is a deadly act, since its role is to immobilize life.

Your work is concerned with the complicated notion of beauty and artifice. Does the context of Paris as a city have any impact or influence on this?

Yes: I live and work in Paris, and I find significant richness there, especially because it is a large cosmopolitan city. To give you an example: when I made a series of portraits of mixed-race young women in 2006, I did the casting myself in the Paris subway.

Where is your studio? What has been your experience of making work in Paris?

My studio is in Paris, in a neighbourhood that feels like a ‘no man’s land’, but I find a large number of resources in Paris, especially because many talented creative people, artisans and technicians live there, whom I can call upon in the making of my own work.

What advice would you offer a young artist about making their way in the Paris art world?

I haven’t got any particular advice to pass on, because an artist’s practice is so highly personal. I think all you need is to set yourself some goals. These goals can take a very long time to reach, so you’ll need to be persistent.

Issue 24 is available now