With a seemingly genuine desire to simply indulge in a long, drawn-out breakfast, rather than to enact any kind of display of power, Valie Export tells me she will be ready to speak by 12.30pm tomorrow, following the opening of her exhibition at Berlin’s Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, and to meet her at her hotel. No she doesn’t want to note down my phone number, and no she doesn’t hand me hers. A profoundly millennial malaise at this fixed rendezvous without the involvement of technology that might help us rearrange in the face of extenuating circumstances plagues me for the following twenty-four hours.

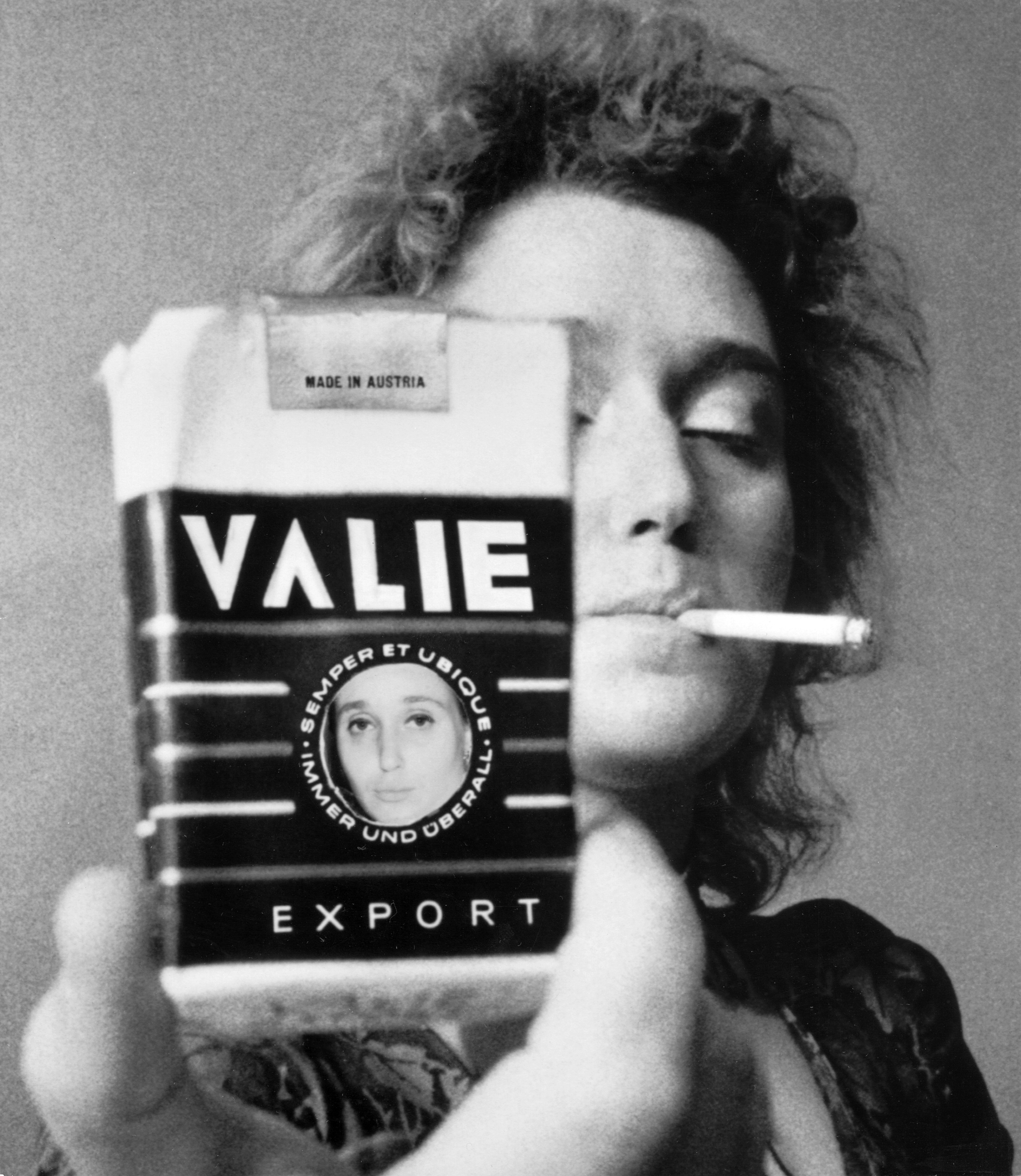

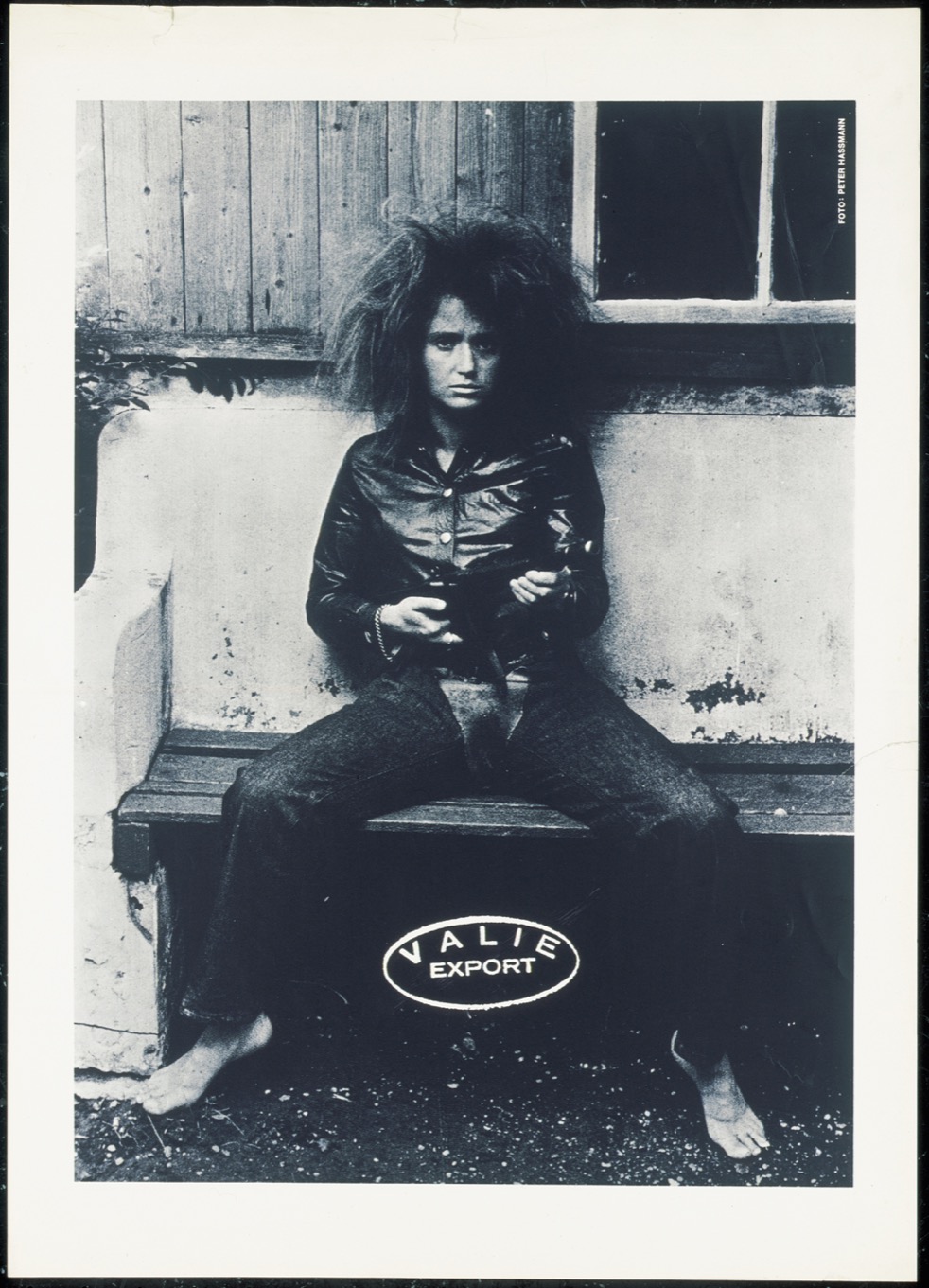

Any anxiety over our meeting materializing dissipates quickly. Right on time, unaccompanied, Valie Export meets me in her hotel lobby and we settle into some ugly armchairs and begin discussing the importance of archiving to a soundtrack of Ariana Grande over the tinny hotel speakers. “I never had an archiving system in place,” says Export—whose name is one of her own appropriation, shirking her paternally and latterly marital given names in favour of one borrowed from a brand of Austrian cigarettes—“I used to stuff documents and photos into plastic bags and folders. But it was, and still is, an incredibly important part of my working process.”

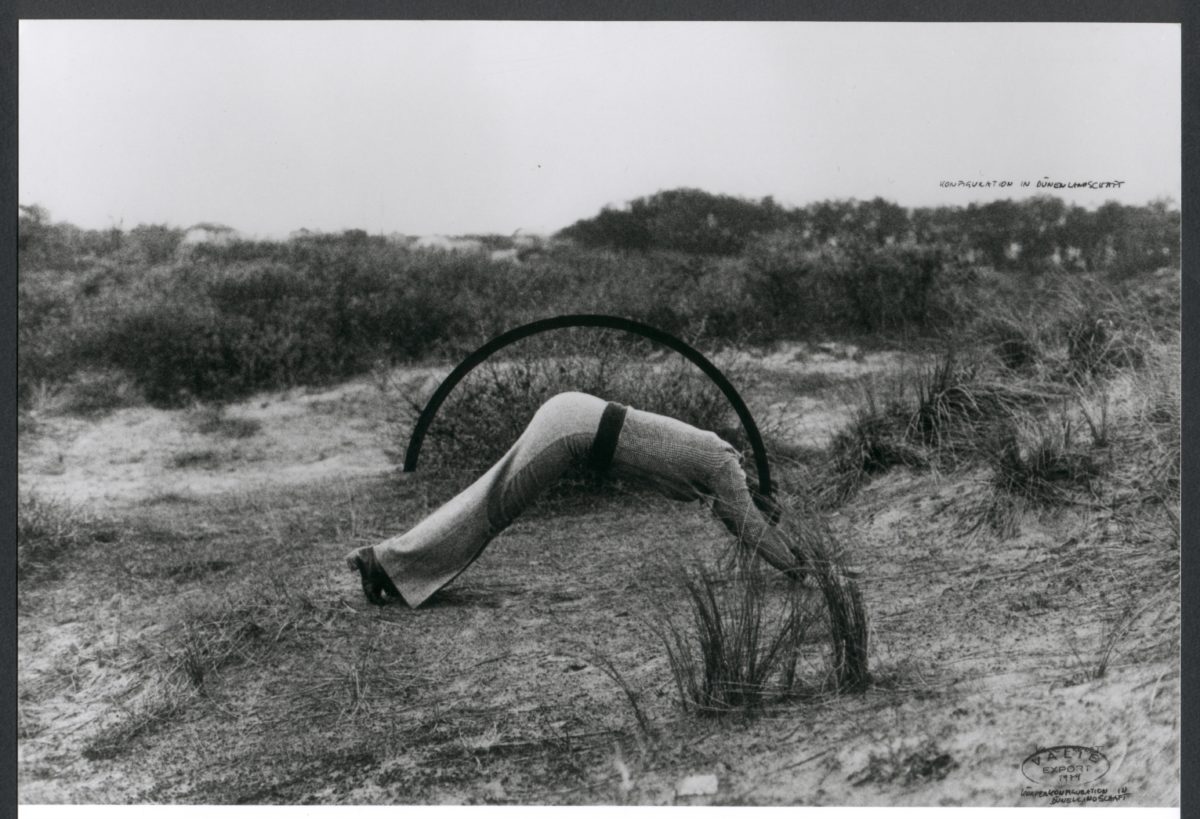

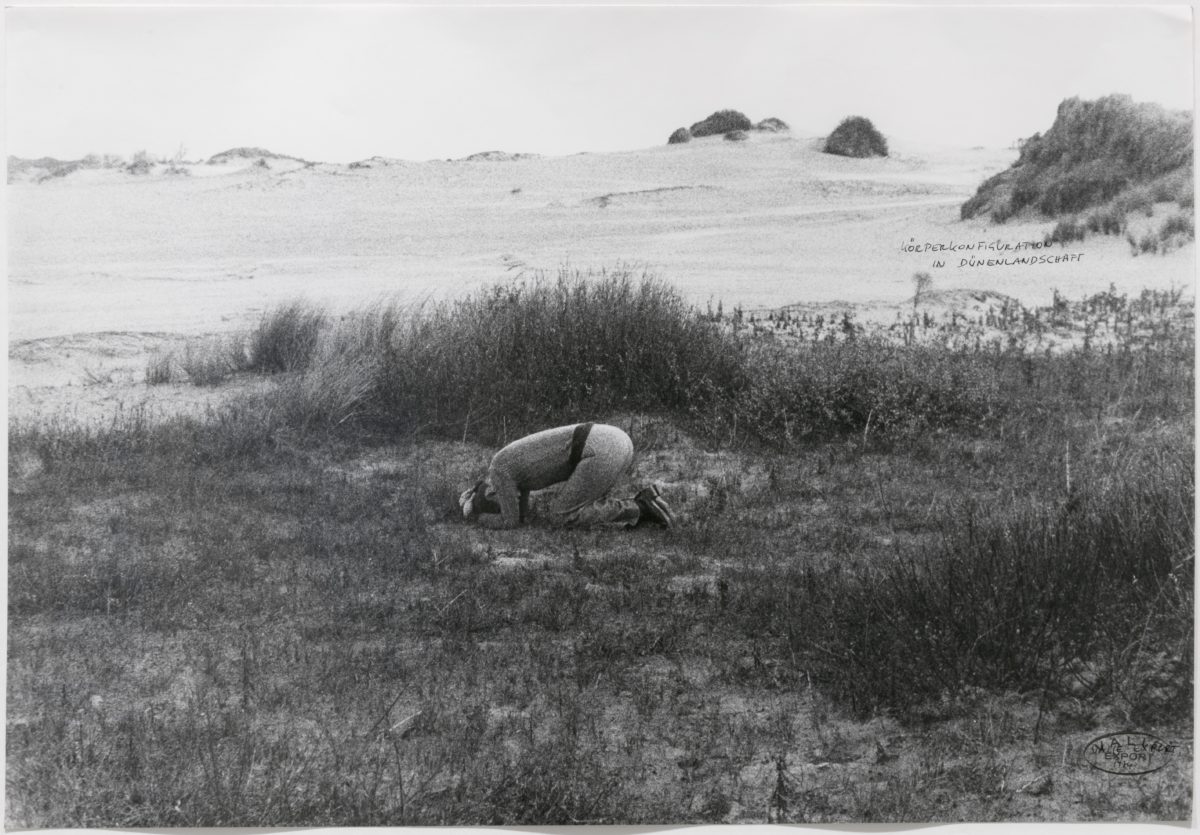

- Konfiguration in Dünenlandschaft, 1974

Her exhibition at the N.B.K this summer opened with a quote from critic Jürgen Thaler, “Je unsicherer die Zeiten, desto lückenloser muss die Sicherheit in den Akten hergestellt werden” (“The more insecure the times, the more necessary careful archiving becomes”). At the moment of writing, times are not only turbulent, unstable, ever-changing, but a highly worrying symbolic destruction of archival material is underway; on 24 May 2018 the last research associate at the Georg Lukács Archives of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences was barred from entering the archives, signifying their indefinite closure. The potential for dangerous collective societal amnesia is undeniably on the agenda.

“I was against a certain brand of radical feminism during the seventies, which said ‘We don’t want power, we don’t need power, power is male.’ I believe we need power”

Export meticulously archived, not just out of a sense of posterity or personal impulse, but with an awareness of its importance in such a politically engaged body of work. Coincidentally, while contextual paradigms may have shifted, much of her work, most prolifically created through the seventies and eighties, addresses social and political issues which remain very much unresolved: the control of women’s bodies by men, the conservatism of “art” spaces, the voyeurism of mass media. As such, any archival material available from throughout her career becomes an important strategic tool to confront these issues in their contemporary iteration. “I’m still archiving today,” says Export, “I hold on to things while I need them, and then I send them to the Valie Export Centre in Linz so they can become a tool for others.”

Export, whose vagina I am well acquainted with through various photographic representations, whose big, black-outlined eyes appear in hundreds of images from the seventies—challenging and sexually charged—is now seventy-eight years old. Her life’s work is a masterclass in strategies for resistance. Her iconic 1968 Touch Cinema

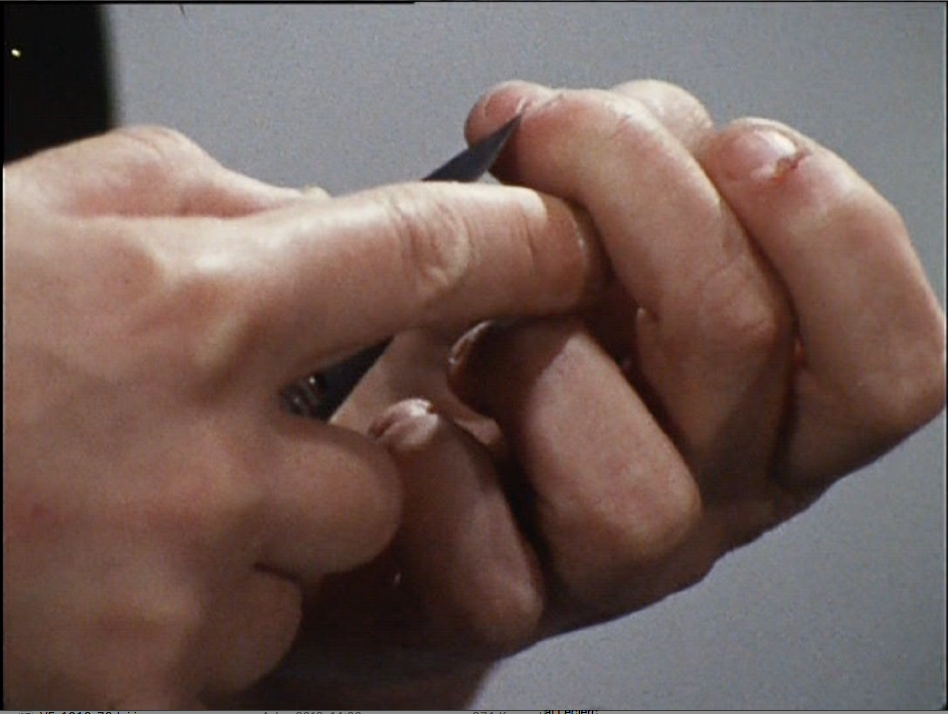

performance took on the male gaze and the voyeurism of cinema with the aid of a cardboard box strapped to her bare breasts. Participants were invited to look and touch, but in touching they would become the object of observation by those around them; they would equally be confronted with their complicity in the male gaze, having to engage with the female body they were objectifying. “They hated this contradiction,” she states in the 1999 Angry Women anthology, “that the object of desire is standing in front of them, you can have it, but you have to do something for it.” Her 1973 …Remote… Remote…

saw her gruesomely chopping away at her cuticles before sinking the tips of her fingers into a bowl of cool milk, an explicitly legible metaphor for the violence of societal beauty standards that women are held to. “My art was aggressive,” she tells me, “aggression is provocation, and my viewers do not have to think like me, but they have to be provoked into forming their own opinions, their own reactions.” Her body became a site in which both the private and the public played out, it mapped a compendium of societal issues. “These performances had a real feminist agenda, they used the vocabulary of the times, during the seventies, but they are still readable today.”

Moreover, Export’s work exited the institutionally validated realm and confronted new cinema-going, street wandering, uninitiated audiences. She addressed a broad spectrum of a society largely unwittingly complicit in a throng of forms of oppression. But these non-institutional actions were not only strategic, they were enforced, “We were forced into underground and experimental spaces as well as public spaces, because women weren’t invited by museums or galleries to exhibit.” Export has spent most of her career on the peripheries—it only adds to her aura of self-assurance, her radicalism, her commitment to her causes, that she has simultaneously been granted utmost art-world respect, yet she has not been swept along and flattened into a simple artist-celebrity. She was not just another proponent of Viennese Actionism (she was a Feminist Actionist). Based in Austria she was geographically removed from the explosion of the concurrent New York art scene; she was the object of public vitriol for her outrageous work, and yet she never felt like she was working in isolation. “I was still connected to a scene,” she says, “in Germany during the 1970s, female filmmakers were very powerful. I met with Carolee Schneemann

and Margarethe von Trotta during this time, Luce Irigaray was writing important texts on feminism; it was a small group but we wrote letters to one another, we were together through books, we shared knowledge.”

“The vocal chords are like a hairy ass, it is the same for a man or a woman”

The “we” she is using is not royal; it is collective and explicitly feminine. However her fight is not staidly binary: “I was against a certain brand of radical feminism during the seventies, which said ‘We don’t want power, we don’t need power, power is male.’ I believe we need power. If you don’t have power you can’t change anything,” she states. “People think that there is a fight between the genders, but we don’t have just two genders. We need power to address this.” Her most recent performance at the Venice Biennale in 2007, The Voice as Performance, Act and Body (The Pain of Utopia) demonstrated an intelligent evolution in her work on this very subject. Rather than focus on any specifically gendered element of human corporeality, Export filmed close-up images of the inside of her throat and nose whilst reading a text she’d written entitled “What Is the Anatomy of Language?” If her work from the seventies unveiled the ways in which women’s bodies were (mis)treated in a more explicitly patriarchal society, then her recent work addresses the ways in which women’s bodies are constructed in a more insidiously patriarchal society. “The vocal chords are like a hairy ass, it is the same for a man or a woman. The beginning of the piece is neutral; the vocal chords move up and down, it is through the other anatomical architectures needed for speech that the body becomes then male or female, or something else.”

There is much that makes Valie Export’s oeuvre cohesive, yet there is one clear factor that makes it continuous, and that is her unwavering physical presence. Her physicality is inextricable from her artworks, or even the theorization of them. “There is a unification between my identity as a person, and as an artist,” she says without a shred of nostalgia or self-aggrandisement. “My body was a material—I used my body as a tool to make art. I wasn’t an actress, I was part of the art piece.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 36

BUY ISSUE 36