“Bureaucracy is just swapping papers,” says Vanessa Baird, shrugging underneath her fur coat inside the sleek R6 government office building in Oslo, Norway. Gazing up at the Norwegian-Scottish artist’s massive painting that overtakes the back wall of the building’s media room, I barely notice the documents scattered across the canvas. A hungover-looking skeleton keeling over a chopped tree trunk in the bottom left corner and a pair of demonic Scandinavian siblings in the top right—the boy’s hands melting into the fire, with his head rotating a full 180 degrees to grin down at us in Exorcist

-grade horror—are just a couple haunting details that demand my immediate attention.

“Dark water and drowning refugees periodically wash over the narrative; Norwegian wood, erections and excrement abound.”

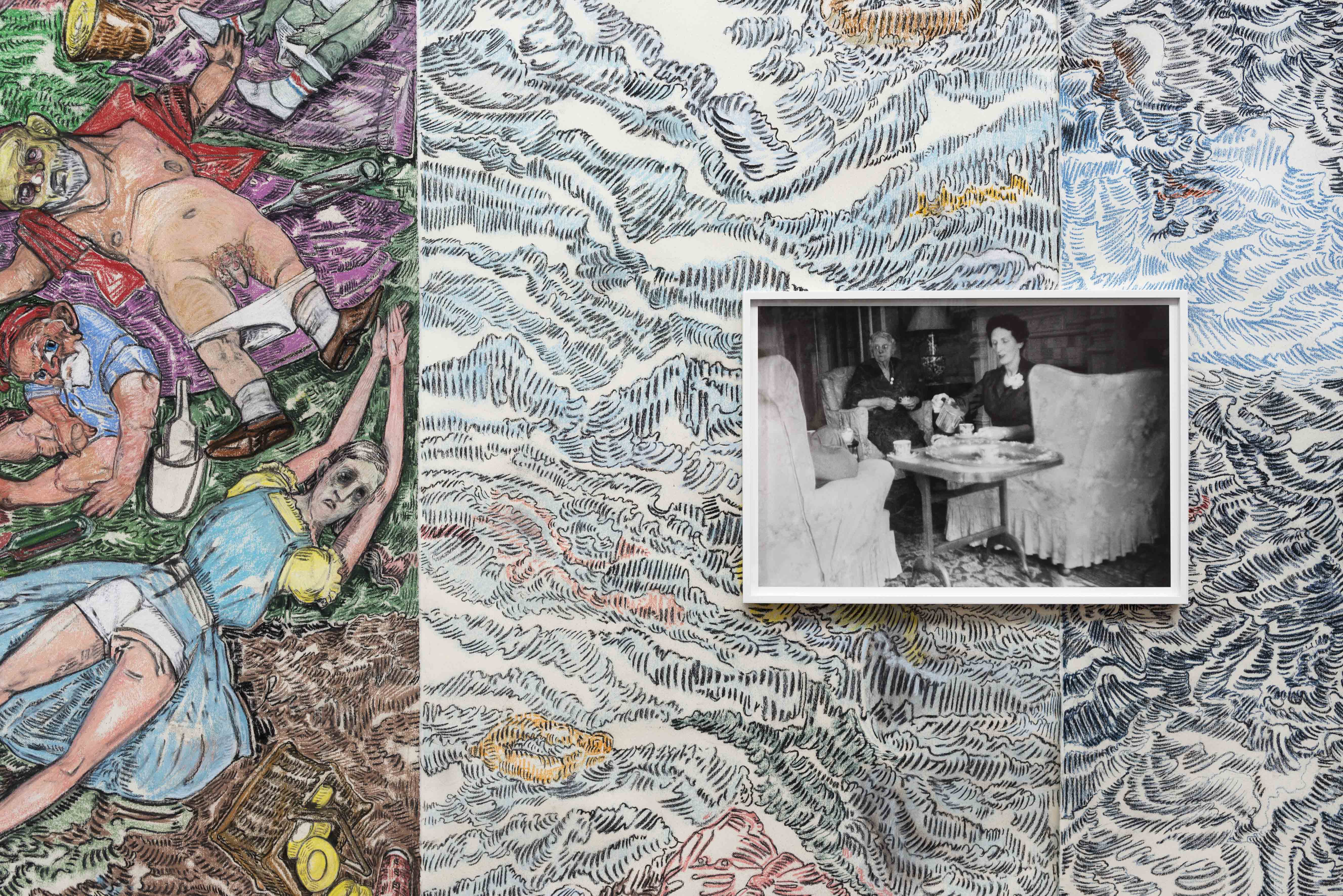

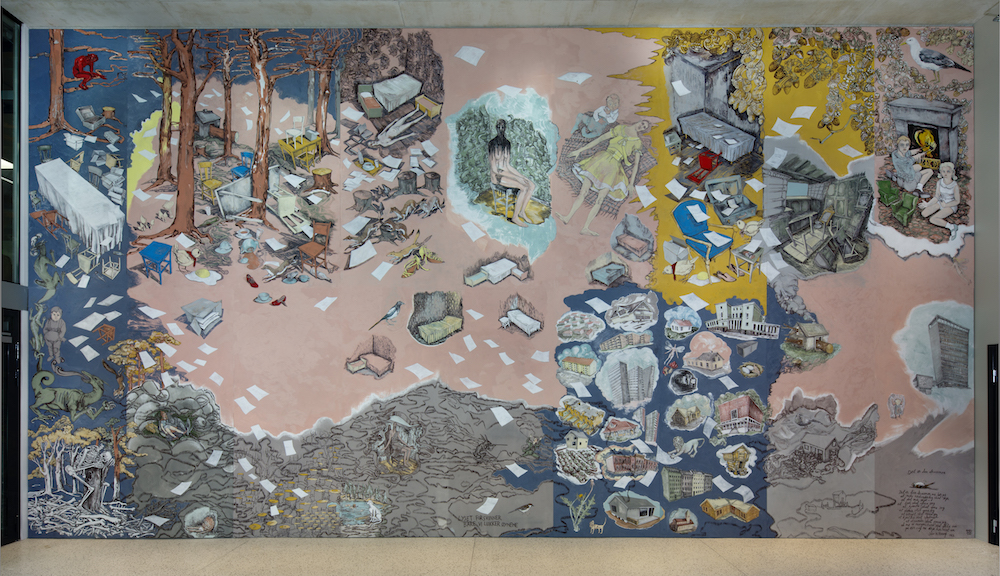

We’re here to celebrate the debut of You Are Something Else (2017), Baird’s new commission on display at the Kunstnernes Hus for which she won the 2015 Lorck Schive Prize—as Norway’s highest art honour it boasts a monetary award of NOK 500,000 (£60,900 USD). An epic floor-to-ceiling drawing where unspeakable violence and smutty excess are interlaced with Norwegian folklore, Baird’s newest work—like all of her oeuvre—comes in layers that pull as freely from contemporary politics and planetary crisis as her personal life.

Baird’s relationship with Oslo is also something else. It transgresses the art world and weaves into the cultural memory and trauma of the city, and is as vital to understanding her practice as it is complex. But before delving into her latest coup, it makes sense to scope out the rest of her work across the city. So, back to the government office.

“At first it was like a second skin for the building, and nobody noticed the papers. But then the bomb went off and it all changed. Suddenly everything was very fragile.” Baird’s referring to the terror attack on 22 July 2011, when homegrown terrorist Anders Behring Breivik bombed a government building in Oslo and went on a subsequent shooting massacre on the nearby island of Utøya, killing seventy-seven people in total. It’s the most violent attack in Scandinavia since World War II, and for many Norwegians, the lack of comparable events in the country’s modern history keeps its public memory visceral and traumatic to this day. And because of the association drawn between mass-circulated security footage of the blown-out building that depicted documents flying amid the smoke and debris and the papers swirling around Baird’s painting, the artist found herself in the midst of a drawn-out controversy taking aim at her work.

Despite her tendency to shun the spotlight, Baird made an adamant stand against what she saw as an inane comparison. “People blew it way out of proportion. They saw the papers and immediately connected the painting to the bombing. Then it all became a symbol of the attack somehow. But it’s ridiculous; for instance, if you see a tree, do you want to hang yourself? You can’t just cut out the tree.”

The government ordered for curtains to conceal the painting while the controversy peaked, and in no small batch of irony, Light Disappears as Soon as We Close Our Eyes (2011) was then plunged into darkness. Nowadays, that curtain is more or less unused, yet the provocative question of censorship lingers on, and the future (re)location of the commissioned work remains uncertain. Meanwhile, Baird has become something of a patron saint of free speech among Oslo’s budding art scene, which bristles with plenty of activist-oriented young artist collectives and studio spaces.

“My whole life, I’ve been told to quiet down,” she shares on the journey over to the Arts Council building, the new home of the ostracized painting To Everything There is a Season (2014). “But I do speak out, in my own way.” Not one for grand confessionals, most of Baird’s introspections come unprompted and raw, drawn out like a savoured secret.

“My mother is also an artist,” she continues, “And there has always been a sense of competition.” Baird has lived in the same house since birth, along with her parents, siblings, husband and daughters. It becomes easy to see how the narratives of her personal life thread through her work so pervasively to develop a vine-like chokehold that’s as visceral in her art as in her life. I recall an earlier conversation with Baird in 2015, where she’s asked if Norway influenced her work. “As I don’t have any other experience than being born and brought up in Norway I wouldn’t know,” she responded. It suddenly dawns on me that for Baird, her cultural identity and her physical home are one and the same.

Entering the Arts Council I stumble upon To Everything There is a Season soaked in sky light. It’s majestic. Buildings, bodies, Norwegian forests and more fluttering papers are revealed throughout a pale pink cloud that stretches across the entire composition. Someone makes a comment about the painting feeling much more connected than the last and Baird practically glows. She races to the adjacent bookshelf and grabs a collection of her drawings to help us decode the work.

“Pinks and blues, my family… it’s like a wallpaper: beautiful from far away and then you get close and it gets terrible.” She speaks in fragments, flipping through the book, her mind racing. A gaunt figure, collapsed into a long armchair, reappears often. “My father with his cancer legs…” her thought trails off and her expression tightens. Then she laughs. “I’m not that depressed anymore. I think.”

“It’s both a forced reckoning with the ugliness of our collective political moment and a total repudiation of the outdated regulations that caused it.”

Outside, we speak of her dyslexia, isolation and foreignness; feeling like an outsider in one’s home. “At school in Oslo, people would say, ‘You’re not a painter, you’re not a drawer. Your work is too illustrative, too this and that,” she shares, and I ask about her brief elope as a student at the Royal College of Art in London. Her smile grows wide; fond memories flood forward. “In London you can do whatever you like. You meet all sorts of people.”

Armed with this context, I finally trudge up the stairs to the Kunstnernes Hus amid a 3pm winter sunset, drenched with rain and slightly buzzed on champagne. I’m not prepared for what You Are Something Else will do to me. Spanning the entire gallery like an epic Rubens tapestry, it unfurls piece by piece in uncoated strips of parchment; their order is inexplicable but still somehow comprehensible. Dark water and drowning refugees periodically wash over the narrative; Norwegian wood, erections and excrement abound (“Fifty shades of brown,” Baird jokes.) Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights could be a fair comparison.

“It all seems to suggest that the apocalypse is still apocalyptic, but also brings a chance for new life.”

But here the violence and vulgarity feels more urgent. In her latest work, Baird directly engages with the most salient global crises, from rising waters, contamination and deforestation, to mass migration and cultural displacement. It’s both a forced reckoning with the ugliness of our collective political moment and a total repudiation of the outdated regulations that caused it: presented here as the art historical canon, of framed bourgeois portraits and religious figures, whose painted faces Baird smears with shit.

Yet amid all the doom and gloom, there is a glimmer of hope. Reading the tapestry from gallery entrance to exit, the dying woman at its beginning is ultimately replaced with a healthy patch of green grass, blanketed babies, and a dormant mother who is—almost—smiling. Beneath them, the text “I am, You are, She/he/it is, They are,” is written in a whimsical but firm cursive script. It all seems to suggest that the apocalypse is still apocalyptic, but also brings a chance for new life. Optimism—and the vulnerability of hope—is a new step in Baird’s practice. But as her work suggests, to everything there is a season, and hope may be our only option when there’s nothing else left.