The work of Bridget Riley (b. 1931) has always created something barely there, disappearing even as you glimpse it. At the preview for her new show Recent Paintings 2014–2017 at David Zwirner in Mayfair, the 86-year-old artist appeared unannounced to speak for a few minutes and vanish again. She rarely does publicity for her work. The gallery only knew she’d be coming thirty minutes prior to her arrival. This sums up not only Riley’s career and her process, but her art. It is a vanishing point for both the viewer and the artist. Whenever she feared she was becoming too visible, she retreated. If ever critics classified her work as one thing, she did something else. Just when she was about to reach a new level of success in the ‘60s, she rebelled against the public desire for her and disappeared into another style.

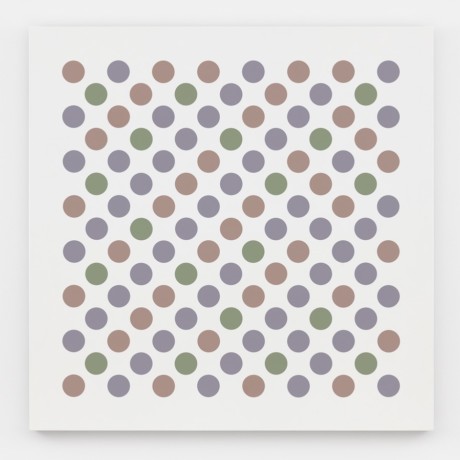

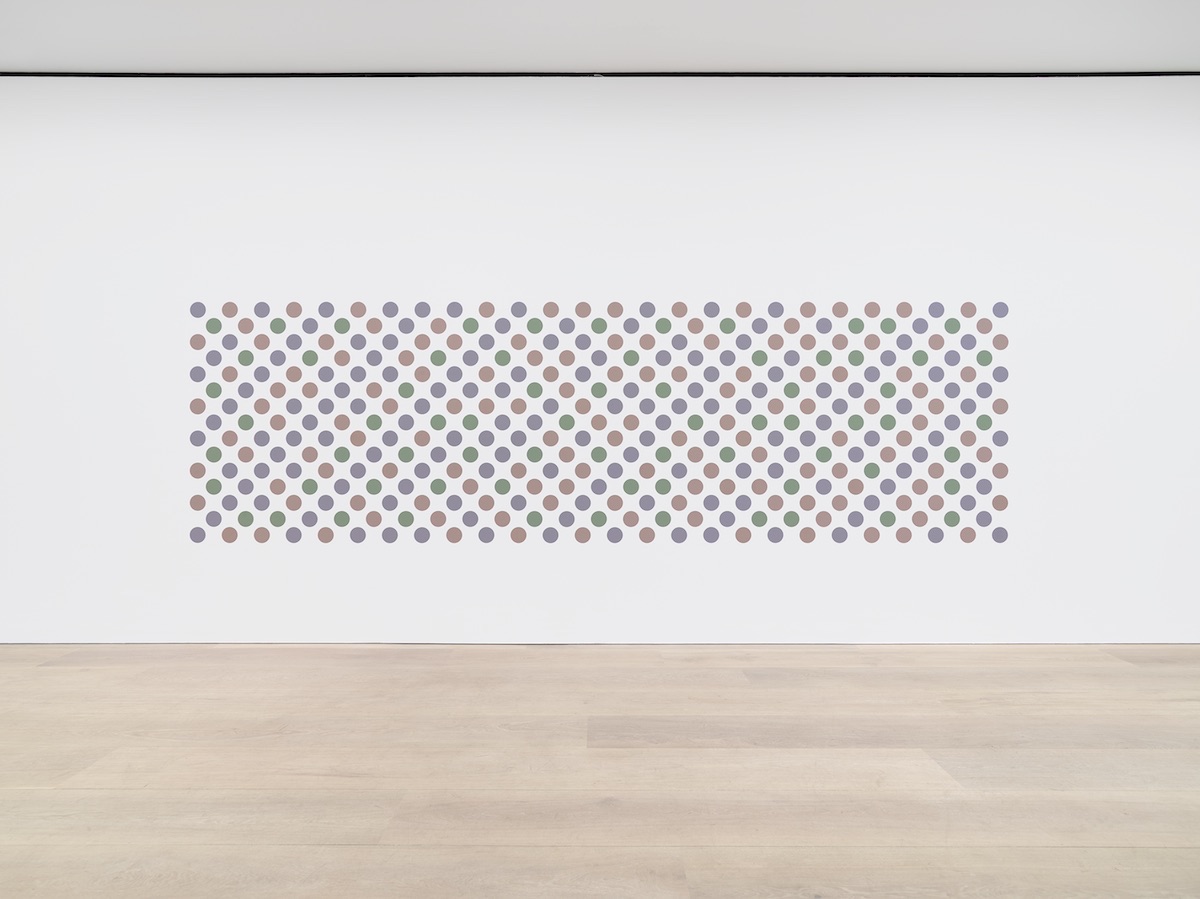

The top floor of the exhibition at Zwirner explores a recent series, Measure for Measure, comprised of three colours that morph to more depending on their arrangement. There is a dull purple, a matt green and an orange close to brown. Cast your eye across Untitled 2, which takes up an entire wall, and shades of pink are cheekily implied amidst the painted discs. You chase your own retinal artwork around the wall as it vanishes, unique to each set of eyes. One viewer felt the discs coming out of the wall, another saw them receding. This is the Riley dichotomy. They look scientific, and in fact are scientific––in that their effects have been precisely, mathematically considered. But, as the artist explains during her fleeting visit, they are “not factual”. The truth of them is as elusive as those ghostly discs, retreating with the artist behind her forms.

After immersing herself in the figurative old masters – Raphael, Rembrandt, Ingres – at Goldsmiths and the Royal College of Art, Riley was introduced to Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. She fell especially for the work of Jackson Pollock, and looked further back to Paul Klee, Futurism, and Seurat (whose works were shown alongside hers in 2015 at the Courtauld), deconstructing how he used colour to imply a language beyond it. She became interested in everything the eye could consciously or unconsciously do; how the canvas or wall could suggest images as well as creating them.

“You chase your own retinal artwork around the wall as it vanishes, unique to each set of eyes. One viewer felt the discs coming out of the wall, another saw them receding. This is the Riley dichotomy.”

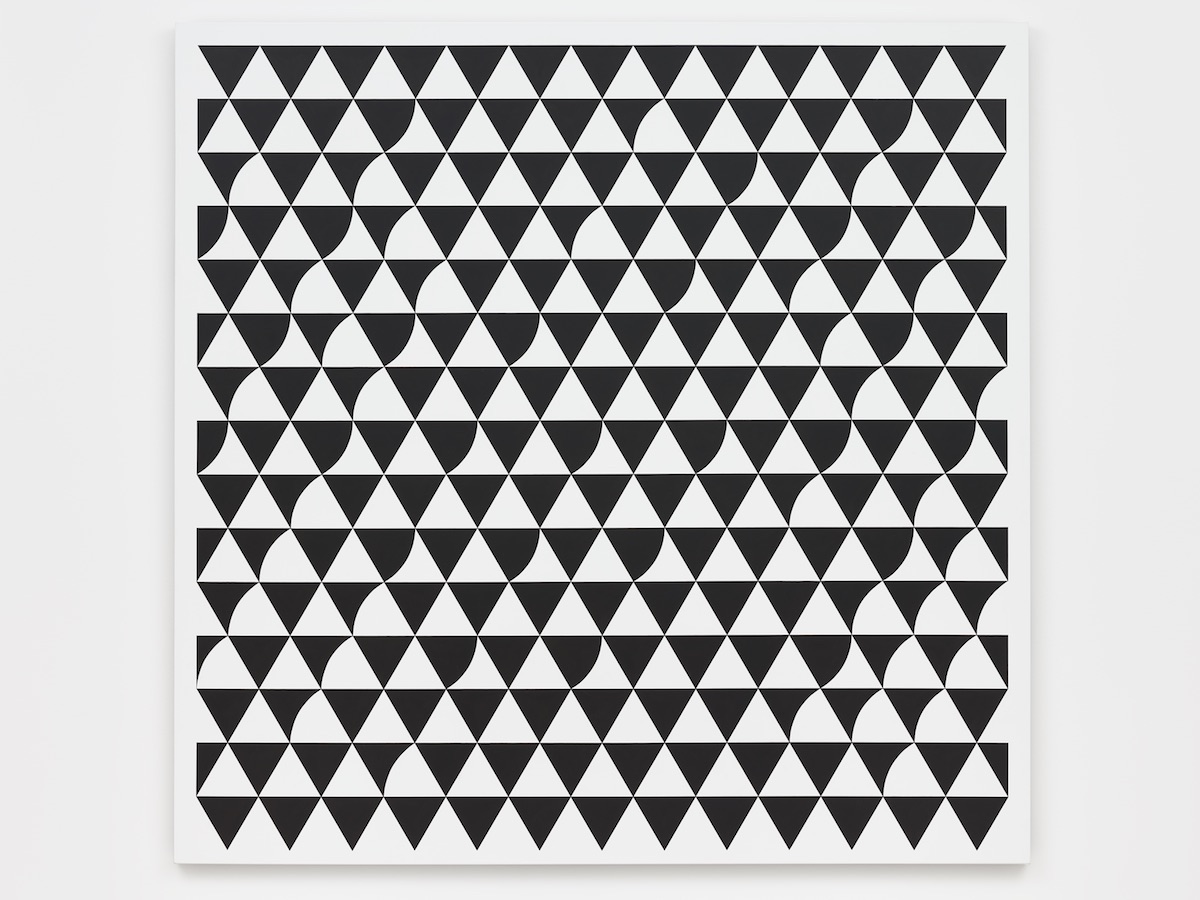

Her work became known as Optical Art, or “Op Art”. Monochrome shapes placed to make the viewer not only question their way of seeing but luxuriate in it, as one might in the brushwork of a Rembrandt. In the context of the decade, audiences found her work challenging, hallucinogenic; radical in a way that was nonetheless completely in step with the psychedelic revolutions taking place in other media. Trippy, basically. The work of abstraction moved from the artwork onto the viewer’s own instrument of perception, as narrated by 1965’s The Responsive Eye, a seminal MoMA exhibition which featured Riley’s work on the front of its catalogue. In her mid-30s––roughly the age Tracey Emin would be when she achieved peak YBA fame thirty years later––the British Riley became the talk of the New York art world.

After the MoMA exhibition and a sold-out solo show at the Richard Feigen Gallery, artists fell over themselves to associate with her. Salvador Dali introduced her to his pet leopards. Her popularity gave rise to her work being used on Fifth Avenue dresses, posters and lampshades. The idea of Bridget Riley matchboxes was even floated. But unlike artists of today, who are encouraged to crest this wave, Riley chose the moment of its arrival to submerge herself. She sued, went back to London and changed her style, incorporating colour into her recognisably monochrome palette in 1967, with works like the stripe paintings Late Morning and Chant 2. Just when the world presented her an opportunity to milk the black and white, she vanished into colour. She wouldn’t return to black and white for over 30 years.

The works on the ground floor of the gallery, such as Rustle 6 and Cascando (both 2015) represent her first monochrome work since the late sixties. In the former, triangular units pass in waves over a square. The latter is horizontal, long and thin, baffling you as you sit in front of it. A row of sharks’ teeth, in two layers, seems to chomp across it. Seeing a big group of her works for the first time in the flesh––or rather, in the pigment––you have something of a numinous experience, or a seizure. A powerful early work, Black to White Disks (1962) at first appears to be a diamond of black circles that fades at its edges, but is in fact made of solid rounds of colour.

“Audiences found her work challenging, hallucinogenic; radical in a way that was nonetheless completely in step with the psychedelic revolutions taking place in other media. Trippy, basically.”

In 1961, Riley disappeared from the physical and tactile production side of her art, handing this over to assistants. We might begrudge some artists this decision as the shirking of some necessary imprimatur––Damien Hirst perhaps, who credits Riley as the starting point for his “spot paintings”. But with Riley it seems appropriate. In a 2000 catalogue essay, Dave Hickey describes her work as “clean, fresh, virtually authorless modernism”, something that is consistently felt throughout her career.

She is an artist overloaded with canonical influences who nonetheless seems entirely unburdened by history, or even personality, when you see the paintings. It’s all there, but barely there at all. Just as you don’t need to like art to appreciate a Rubens (in fact, sometimes this even helps) you don’t need to like Rubens to appreciate Riley. You just need eyes. You barely even need Riley for very long, as the mark of her the paintings tends to linger after you’ve taken your eyes away; after she has taken her leave, and after you have left the room.

All photographs © Bridget Riley 2017; All rights reserved. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London.

Bridget Riley: Recent Paintings 2014–2017

19 January–10 March 2018 at David Zwirner, London

VISIT WEBSITE