We’re pushing through the crowds by Rialto bridge, my earrings swinging in the breeze. My first spritz goes down cold and syrupy, like medicine. I drink two more as friends and some artists I’ve only ever seen in Instagram stories congregate outside the Aperol-sponsored bar for an event laid on by a PR firm. We nibble cicchetti of artichoke and fried meatballs.

“The Venice Biennale opening week is the Emily in Paris of the art world,” drawls a curator, coining a quip that they will undoubtedly repeat many times.

St Mark’s Square at night is almost entirely deserted. Walking across it alone on the way home, I feel like I am in a virtual reality simulation of Venice, as if none of it is real. The city is impossible, doomed to disappear into the glistening water, and our arrival alongside thousands of other Biennale-goers is only hastening that.

Another impossibility: an active women’s prison on the Venetian island of Giudecca, which I visit on my first morning. Sixty contemporary female prisoners are confined in a 16th-century nunnery, some for life. Five hundred years ago women were brought here against their will, forced into the life of nuns as punishment for prostitution. Others were sent here simply for being too beautiful too young, held captive until they came of age for their destined suitor.

“The garden is a tender jewel, and moves me more than anything else I see during the week”

French artist Pauline Curnier-Jardin has created a riotous film installation here, working closely over two years with the prisoners to reanimate this history, part of a project curated by Francesco Urbano Ragazzi with LIAF. Also inside is a sprawling vegetable garden, where the inmates work each day, overseen by cooperative RioTerà dei Pensieri. It is a shock to see sprouts emerging from the soil in a city where almost everything is shipped in, from champagne bottles to works of art. The garden is a tender jewel, a delicate resistance against circumstance, and moves me more than anything else I see during the week.

This Is Ukraine at Scuola Grande della Misericordia, Venice

The war in Ukraine looms over Venice, present at parties, in handshakes, in laughter. This Is Ukraine: Defending Freedom, a lavish exhibition staged by the Pinchuk Foundation, brings together artists including Maria Prymachenko, the folk artist whose work was destroyed in the bombing of Ivankiv Historical and Local Museum in February. Nikita Kadan displays domestic items destroyed in shell attacks, the debris collected from eastern Ukraine and shown alongside archive imagery and idyllic postcards of the region.

Upstairs the spell is broken by international art world heavyweights such as Damien Hirst whose large-scale painting of the Ukrainian flag, peppered with his signature butterflies, feels facile and self-indulgent. Elsewhere tote bags with the block colours of Ukraine flutter on the arms of biennale-goers throughout the week. It is an inherent contradiction that no one can look straight in the eye.

“That evening a lone bartender with a flimsy corkscrew is desperately fending off the hoards of partygoers”

That evening a lone bartender with a flimsy corkscrew is desperately fending off the hoards of partygoers, dribbling wine into outstretched empty glasses held by jostling arms. Nearby, warmed trays of risotto and lasagne are slopped onto plates for guests wearing open-necked shirts and suit jackets. It’s as if the school dinner line has been transported to a palazzo, complete with the social anxiety about which table to sit at.

At the British pavilion party full bottles of pink gin line the bar, and we are foolishly invited to top up our own drinks. It’s not long before the alcohol takes powerful effect. I am with a group of young architects who shout and whoop with excitement, a welcome change from the stony-faced collectors and curators who see this as just another event on a packed itinerary. The DJ belts out 1990s British classics. Sonia Boyce, who is representing Britain at the biennale, climbs up onto the raised stage and dances with infectious delight to cheering.

“Have you seen Sonia?” a girl asks our group when the party ends. We clarify: “Sonia Boyce?” “Yes. She’s my mum.” It’s a strange moment of reframing; an artist is never just an artist, never just their full name. They are a mum, a daughter, a friend. Sonia. “We’re so proud. She’s so busy, we’ve barely seen her since we got here!”

No one in our group is on the list for the David Zwirner gallery party at the Bauer Hotel, but we walk over to queue up for it anyway. It’s almost one in the morning. A crowd has gathered outside the smoking area, and we hover nearby looking for a chance to slip in. A man approaches the bouncer and seamlessly slides a 20 euro note into his palm as he glides inside. We try to follow, only to find our path quickly blocked and give up.

I wake up feeling like I’ve drunk a stagnant canal. The bathroom of our Airbnb is occupied so I stick my head out the window and dry heave while gazing at the terracotta roofs of Venice. It’s the best view I’ve ever had while in the throes of an art party hangover. I abandon plans of attending the gallery breakfast on a neighbouring island and instead inhale two slices of tepid pizza and a black coffee to prepare myself for the main exhibition.

“I inhale two slices of tepid pizza and a black coffee to prepare myself for the main exhibition”

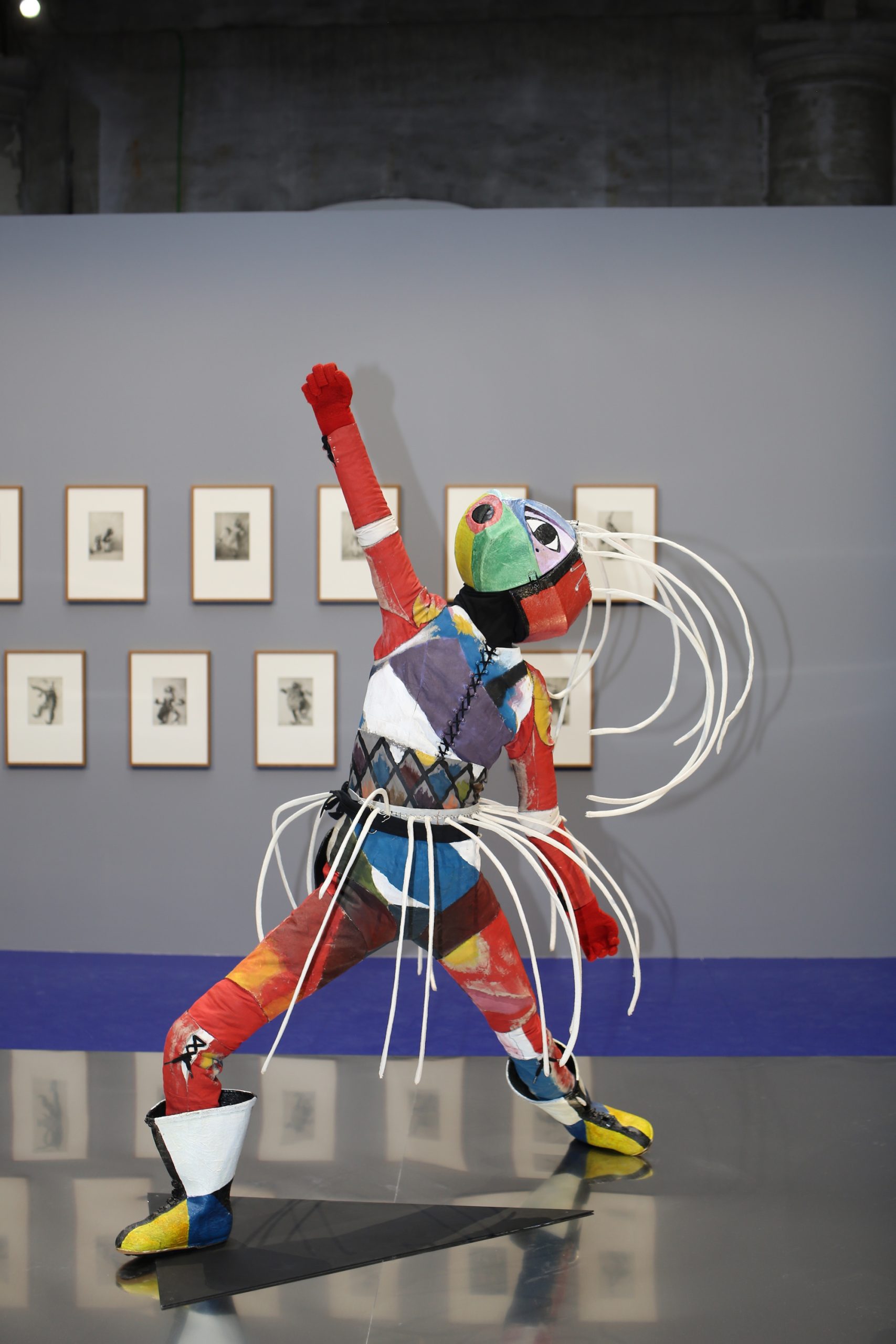

In Cecilia Alemani’s The Milk of Dreams, surrealism is reframed through the fantastical work of female artists, many overlooked in their day. Their ideas germinate in soil fragrant with ground cinnamon and cloves, and emerge as cyborgian part-woman, part-machine dreams. I am drawn to the work of Ulla Wiggen, a Swedish artist who painted diagrams of circuit boards in the 1960s, and used medical gauze instead of canvas.

Zenib Sedira at the French pavilion has created an ode to golden era political cinema, complete with a screening theatre and a detailed recreation of her own living room. At the Belgian pavilion, Francis Alys’ Children’s Games shows youngsters in cities around the world engaged in laughter and play, skipping on the rooftop of a dense Hong Kong estate or racing snails in an Amsterdam playground.

An irate man threatens to sue for wet socks after tripping into the shallow pool of water installed by the artist outside the Brazilian pavilion. I spot Tilda Swinton wandering between exhibitions, and later Steve McQueen. There are whispers of a ladder installed on a far wall of the Giardini for those without early access to gain entrance, but no one will confirm or deny this.

“An irate man threatens to sue for wet socks after tripping into the shallow pool of water installed outside the Brazilian pavilion”

There is talk also of a White Cube gallery party with food piled high as a doge’s feast; a lavish Chanel event; a gathering on a private island hosted by Kehinde Wiley, with Chance the Rapper in attendance. A party in celebration of young British painter Jadé Fadojutimi will be held that night on Murano island, where historic glass factories still produce delicately coloured tumblers and goblets. “Typical Venice,” I overhear someone complain. “Everyone has an invite to a party but no one has an invite to the same party.”

A group of us run in the pouring rain to catch a boat to the Canada pavilion party. We languidly watch a group dance with plastic cups of gin and tonic in an outdoor courtyard at the Korea and Iceland pavilion party (a curious pairing). We fight in a queue for miniature focaccia sandwiches. I need to remember this night, I think, and look around deliberately, staring at the details of a woman’s embroidered coat and the faces of the laughing journalists dancing under the strobe lights.

Another night. At the Scottish pavilion party there are vodka cocktails dedicated to exhibiting artist Alberta Whittle. Who are these events really for, we wonder. It’s rowdy and someone’s nicked a whole bottle of vodka from the bar, which guests take turns swigging from. The drink fuels our walk to another bar, and then another, where we order fried snacks and beer.

“‘Typical Venice,’ someone complains. ‘Everyone has an invite to a party but no one has an invite to the same party’”

A chance encounter leads me and two others to the Swiss pavilion party at three in the morning, where a vast warehouse plays host to a raving mass of biennale guests intent on embracing their last night in Venice. Two enormous pizza ovens have been installed, a marvel after a week of miniature party food. Someone drops a just-baked slice, scalding my leg.

Back at the Airbnb, it’s four flights of steep stairs up with no handrail. I have an image of myself falling onto the cold stone floor below every time I descend them in the dark. I wonder how long it would take them to find me.

I have just a few more hours left in Venice and stalk the streets in search of spaghetti vongole for a solo dinner. Afterwards I buy myself a pistachio ice cream and stand under an awning as it rains again. The tinny beat of a disco tune plays from a nearby electronics shop, and the moment feels like it could go on forever.

Louise Benson is Elephant’s deputy editor

Diaries

Elephant presents exclusive tell-all coverage from behind the scenes at the art world’s international events

READ MORE